- Share via

Eight years ago when Jackie Lacey won the race for district attorney, Los Angeles’ black community celebrated her ascent.

She was the first African American to lead the largest prosecutors’ office in the country.

“I felt like she would understand the fears we face, as everyday black people,” community activist Jerome Kitchen recalled.

“We were all so hopeful to have somebody who looks like us leading the decision-making for once.”

Fast forward to last month’s D.A. campaign debate, and that’s Kitchen on his feet in the audience, screaming at Lacey so persistently that the debate had to be delayed while security guards talked him down. They tried to usher him from his seat, but Kitchen refused to leave or shut up.

Lacey supporters had been cheering vigorously every time she spoke. “I couldn’t stand what I was hearing,” Kitchen said. “Every time she said something I knew wasn’t true, I had to stand up and yell.”

Kitchen’s metamorphosis — from jubilant supporter to distrustful enemy — mirrors Lacey’s political journey, as she fights for a third term as L.A. County district attorney without the support of much of her most loyal constituency.

Crime may have dropped in black communities, but frustration has been growing during her tenure, driven by activist groups and divergent worldviews. As a prosecutor, Lacey views cases through the prism of rules and laws, while others focus on the impact of her choices on people of color.

She sees her job as getting criminals off the street. They’re appalled by a county jail where 80% of the prisoners are black and brown. She wants to tout her success steering mentally ill prisoners out of jail and into treatment. They want to know why she still supports the death penalty and relies on gang enhancements to lengthen prison terms for troubled young men.

“It hurts that we have to take the front line in calling her out,” Kitchen told me weeks after the debate. “But we’re not going to let you slide just because you’re black or brown, if you’re not providing justice for us.”

In interviews and casual conversations over the past few years, I’ve heard some version of “She doesn’t care about us” more times than I can count, particularly from young people who value action more than talk.

Lacey’s reluctance to charge law enforcement officers in controversial on-duty shootings has always been a sticking point. And her silence on the deaths of two black men in the home of a wealthy white Democratic donor really riled people up.

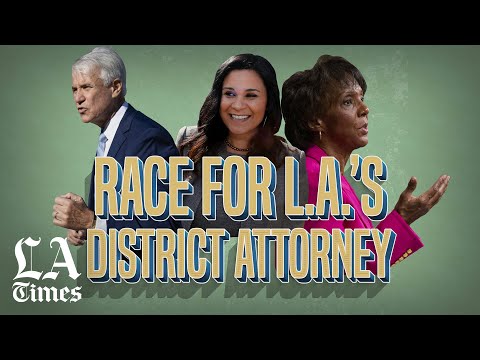

The three-way race for her job has been cast as an ideological contest between competing visions; Lacey’s two opponents are the progressive reformers she once claimed to be.

But it also reflects fissures of race, class, gender and generation that are remaking the political landscape, locally and nationally. It’s been called the most important D.A. race in the country, for its potential to cement a national tilt toward progressive criminal justice reforms if Lacey doesn’t win.

“I really want to root for her,” said Jasmyne Cannick, a political consultant and media strategist who is not on Team Jackie. “As a black woman, this is hard for me. … I may not agree with her politics, but I admire her trajectory. I have a lot of respect for her in terms of breaking ground.

“But this is a test between the old school and the new. We have a responsibility to do better than our predecessors.

“The conversation used to only be ‘who’s toughest on crime’ when it came to a D.A. race. But the conversation is different in 2020.”

I really want to root for Lacey too. As a reporter, I talked with her frequently as she rose through the ranks as a deputy D.A., and she was always thoughtful and forthright with me.

She’s a trailblazer who’s traveled a difficult path, and over the years I’ve seen her heart in action behind the scenes. She was passionate about protecting innocents, especially young sex trafficking victims and people whose crimes were a function of mental illness.

But when it comes to jurisprudence, she seems to have a cautious streak, an aversion to taking on cases that might be hard to win.

Her office declined to file charges against political bigwig Ed Buck, despite the fact that nearly two grams of methamphetamine, along with syringes and drug paraphernalia, were found in his West Hollywood apartment the night Gemmel Moore died of a drug overdose in 2017. Lacey later told a political group that an improper search by sheriff’s deputies “presented a challenge” for prosecutors.

Over the next two years, another black man would die, one would barely survive an overdose, and several more would report to authorities that Buck had forcibly injected them with methamphetamine.

Last fall, Lacey finally announced that Buck was being charged with running a drug den. Two days later, federal officials, who’d run their own investigation, slapped Buck with a more serious charge — providing the drugs that led to both men’s deaths — that could land him in prison for at least 20 years.

The prolonged Ed Buck saga troubled many of Lacey’s supporters — and fed the narrative that her decisions were tainted by politics and tilted toward the rich.

“The biggest issue is that she was not transparent, with the family or the community,” said Kitchen, who was Moore’s closest friend. He claims that Lacey refused to meet with Moore’s grieving mother “to even say ‘I’m sorry that your son is dead.’

“That’s a basic humane gesture. She’s a black mother, she has a son. Why can’t she understand where we are coming from?”

In some ways, Lacey the prosecutor is stranded at the intersection of her moderation and our expectations. That’s a conflict that’s hard to resolve.

Blatant bias in the criminal justice system has shaped black lives for so long, we expect our pioneers to finally right the ship — and feel betrayed when they wind up aligned with the status quo instead.

Kamala Harris had to navigate that same prickly path in her doomed presidential run. She understands the peril of not seeming progressive enough. This week she burnished her pedigree with an endorsement of Lacey’s reform-minded opponent George Gascón, who became San Francisco’s D.A. when Harris left that job.

Even “Auntie” Maxine Waters is bucking the unwritten “support black women” rule in this D.A. race. The legendary congresswoman — a hero in the black community — has also endorsed Gascón.

And the Los Angeles New Frontier Democratic Club, “the oldest and largest African American Democratic club in the state of California,” couldn’t muster enough support for a Lacey endorsement this time around.

Last week I sat through its contentious meeting, which Lacey didn’t attend. Her opponent Rachel Rossi showed up and left the crowd impressed. Lacey needed 60% of members’ votes for an endorsement, but wound up with only one more vote than Rossi, a former public defender. So the group didn’t endorse anyone.

It’s impossible to know how much any of this will matter when voters go to the polls. Lacey was born and raised in South Los Angeles, where loyalties run strong.

But her activist opponents in the community have been waging battle for years. They’ve lobbed insults and shouted her down at public gatherings. And the more they’ve pushed, the more Lacey retreated, refusing to meet with them because of their lack of civility. Which led them to blast her for a “lack of accountability.”

They even staged a predawn protest at her San Fernando Valley home, with a giant “Black Lives Matter” banner and a projector casting “Jackie Lacey Must Go” on her garage door. Police had to escort the D.A. as she left home to head for work.

She’d entered office with the mantle of reformer, but now seems stalled in an era that ties criminal justice to social justice concerns. And young people aren’t worried about decorum or racial fealty as they register their concern.

“We’re trying to find a balance,” said Kitchen, 31, a former nurse and social work student. “As the first African American D.A., our community would have loved to champion and support her.

“But what happened is our ancestors had to keep going along with the process, even when it wasn’t working for us. And we are not willing to do that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.