Police violence against journalists recalls slaying of Ruben Salazar

- Share via

Adolfo Guzman-Lopez, a radio journalist in Los Angeles since 2000, responded with the typical affirmative when he got a request from his editor on a Sunday to cover some news. He’d be out at that afternoon’s anti-police-brutality protests in his home city of Long Beach. Sure thing.

“The march was happening like 10 minutes from where I lived, so I said yes,” Guzman-Lopez recalled. “I got ready, got my equipment, food, water, mask and everything.”

Guzman-Lopez didn’t know then, but by day’s end he’d be reprising elements of a notorious event from 50 years ago, when another nonwhite L.A. journalist went to cover a demonstration and had a brutal encounter with the police.

The KPCC reporter, wearing press credentials and a blue polo, arrived at the peaceful demonstration May 31 and got to work: observing the scene, doing spot interviews and keeping an eye on Long Beach police officers in riot gear holding a line near 3rd Street and Pine Avenue.

He called in details to the news broadcast at Southern California Public Radio. “Just as I said goodbye to the host, things changed,” Guzman-Lopez said. “Police officers started to move up, that caused some of the protesters to get more vocal, start chanting, and yelling louder. That’s when I heard the pop,” he said.

At that moment, the reporter felt a sting at his throat and watched as an object bounced to the ground near him. It was a rubber bullet. In a daze, Guzman-Lopez ran to a parking lot. A few people stopped to help him and noticed blood. “I went to my car to tell my editor what happened, and that’s when I tweeted the picture that’s gotten around,” he said.

The image shows a bloody red welt right at the base of Guzman-Lopez’s throat. (Guzman-Lopez is still recovering and provided audio of a 30-minute interview he recorded with National Public Radio.) He later described a sensation of feeling targeted — a radio reporter, at the source of his voice — for doing his job. “I felt it was a direct hit to my throat,” he said.

The Long Beach Police Department apologized and said it was investigating.

Attacks on journalists by police officers during the demonstrations that spread to all 50 states after the killing of George Floyd have alarmed the nation and brought renewed scrutiny on police practices before large crowds. According to watchdog groups, the hundreds of attacks against journalists documented on U.S. soil this spring amount to the most serious threat to 1st Amendment protections in recent history.

In Los Angeles, the images and videos showing journalists being targeted by law enforcement carried an extra prick of pain for anyone who knows the name of Ruben Salazar.

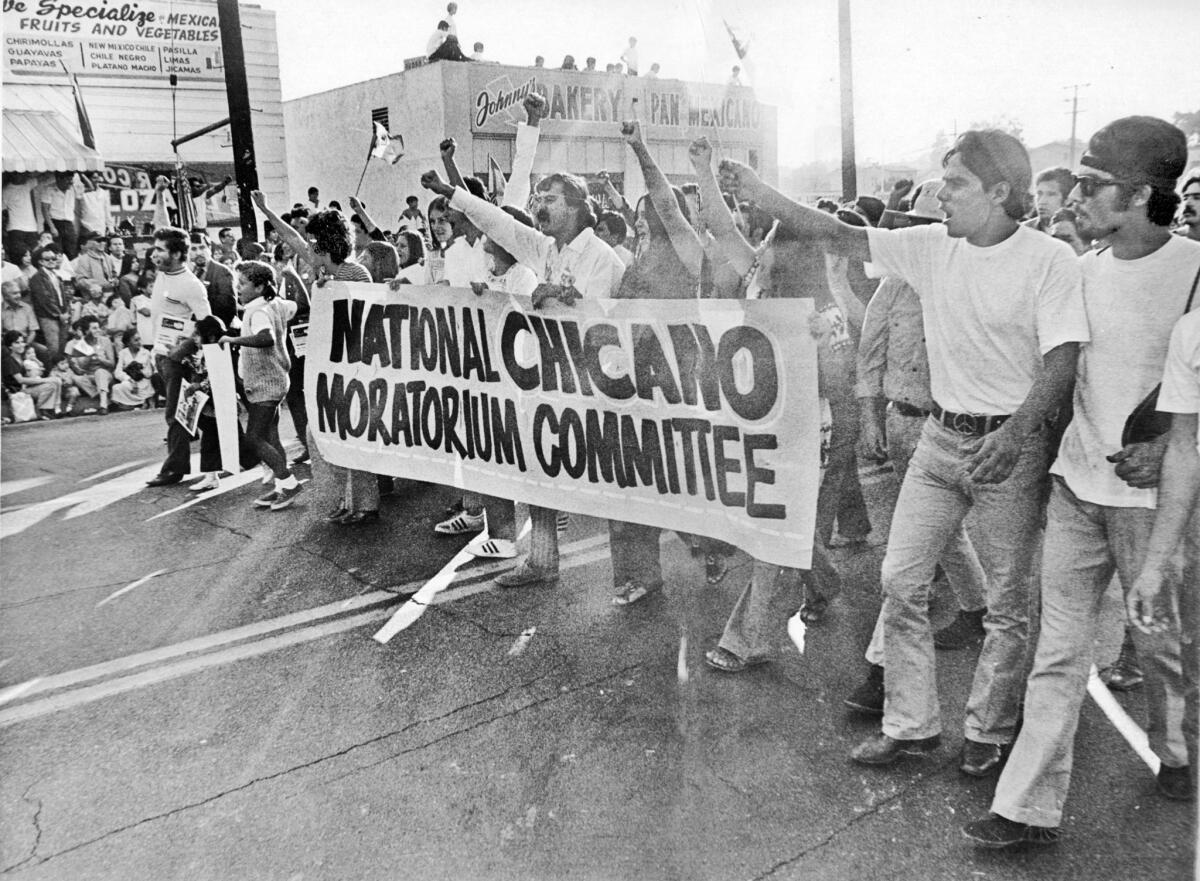

He was the Mexican American journalist whose trailblazing career at the L.A. Times coincided with the revolutionary fervor of the Chicano movement, the youth-led wave of activism and art that coalesced around opposition to the Vietnam War. On Aug. 29, 1970, Salazar was killed when a sheriff’s deputy shot a tear gas projectile into the covered doorway of a bar in the chaos of the police melee that followed the Chicano Moratorium march in East Los Angeles.

Salazar, 42, worked as an L.A. Times columnist and news director of the upstart Spanish-language news station KMEX at the time. He was sitting inside the Silver Dollar Bar and Cafe and was instantly killed when the projectile struck his head.

No journalists have been killed so far in the Black Lives Matter protests this year, but several have suffered serious injuries. And for many in Southern California, analogous elements between 1970 and 2020 are hard to ignore.

“When I saw Adolfo Guzman-Lopez post that picture of him shot in the neck, the first thing that popped into my mind was Ruben Salazar,” said Mekahlo Medina, a local broadcast journalist and a former president of the National Assn. of Hispanic Journalists.

“It worried me a lot,” Medina added, particularly because this year is the 50th anniversary of the movement known as the National Chicano Moratorium Committee Against the Vietnam War. “We certainly didn’t want to see another [case like] Ruben Salazar.”

Salazar, one of the earliest nonwhite reporters ever published in the Los Angeles Times, built a storied career at the newspaper. He amplified issues facing the Mexican American community, which had long been demonized in the pages of the newspaper, and served for a time as bureau chief in Mexico City.

His death was ruled an accident after a public inquest that year and was reconfirmed as unintentional after an official review by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department in 2011. Yet doubts about those conclusions linger five decades later. Today, the Ciudad Juarez-born Salazar is memorialized on a U.S. postage stamp and in a display in the Globe Lobby of the old L.A. Times building downtown. He is one of four Times journalists who’ve been killed while reporting in the nearly 140-year history of the newspaper.

On Tuesday, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors passed a motion unanimously that asserted the 1st Amendment rights of working journalists to document and investigate publicly relevant news events. The motion states that the board “opposes the targeting, harassment, use of excessive force, and arrest of members of the free press by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Los Angeles Police Department, or any other law enforcement agency in Los Angeles County.”

The supervisors named specific cases of L.A.-based or L.A.-representing reporters who were injured or suffered damage to their equipment during the George Floyd protests in late May and early June, including Cerise Castle of KCRW (FM 89.9); Lexis-Olivier Ray, a photojournalist and reporter with L.A. Taco; UCLA student journalist Jintak Han; and L.A. Times staff photographer Luis Sinco, whose camera was destroyed by a rubber bullet.

“There was no warning, no,” Castle said of her case, in which Los Angeles police struck her at the May 30 protest in the Fairfax district. She spent several days on crutches afterwards. “No order to disperse, no one saying this was an unlawful assembly.”

The resolution also made note of injuries suffered by two other L.A. Times journalists while covering a protest outside a police precinct in Minneapolis, where Floyd was killed May 25. National correspondent Molly Hennessy-Fiske and veteran photojournalist Carolyn Cole documented their own injuries at the hands of the Minnesota State Patrol in pieces subsequently published by the newspaper. They said they were clearly identifiable as members of the press.

“An officer came so close I could feel the full force of the pepper spray go into my left ear and eye,” wrote Cole, a Pulitzer Prize winner who has covered conflict zones around the globe. “I’m very fortunate that this is the first time in 25 years at the L.A. Times that I’ve been injured. My left cornea has been damaged by the pepper spray, but I’m hoping it will heal quickly so I can get back to work.”

- Share via

Times photographer Carolyn Cole is struck with pepper spray by Minneapolis authorities Saturday while covering protests over George Floyd’s death.

Hennessy-Fiske was hit about six times in the leg by either rubber bullets or a tear-gas canister, she said, leading to swelling and bruising, seen in images she posted on Twitter. She’s back to work this week and is intent on staying focused on the story at large.

“I’m not going to stop reporting because this happened,” Hennessy-Fiske said. “If the message is, ‘Go home, don’t be reporting,’ my response is, ‘I’m going to keep reporting, and part of what I’m going to keep reporting on is you.’”

The Times is now sending reporters to cover demonstrations with helmets, in addition to the masks required because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Local reporters and photographers said the chaotic days of late May and early June saw multiple incidents of police not respecting 1st Amendment freedoms as they sought to disperse or contain demonstrators. In some instances, police seemed unable or unwilling to differentiate between protesters and press. In addition, the reporters struck by law enforcement in L.A. County and cited by the county supervisors are all nonwhite.

Virginia Espino, a researcher who teaches at UCLA about the Chicano Moratorium and Salazar’s death, said the L.A. press attacks carried an undeniable racial factor. “I think some of those journalists got shot at because they weren’t blond,” Espino said. “Even if they had their press passes showing, they were viewed as one of the masses protesting at that time.”

“It’s something I’ve experienced, where law enforcement or people in authority question my credentials often,” said Castle of KCRW. “And it’s something I’ve seen happen to other journalists of color.”

Samanta Helou Hernandez, an L.A. freelance journalist and photographer, found herself detained by Los Angeles police June 2 after being chased by officers while covering a demonstration outside the Getty House, the official L.A. mayoral residence in Windsor Square. She said she repeatedly told police she was press. But as a freelancer, she was not carrying credentials issued by a news organization. So Helou Hernandez was corralled with demonstrators.

After talking to an officer, she said, “He basically said, ‘If you’re press you should have run toward the police,’ which to me sounded ridiculous. You’re telling me to charge toward the police while they’re in full riot gear, come on.”

She was also told that because she didn’t have credentials, she’d have to be taken downtown to “plead her case.” At that moment, she saw a colleague, Ray of L.A. Taco, who stepped in and pulled up journalistic work by Helou Hernandez to prove she was working press. “That’s when the tone really changed with how I was treated,” Helou Hernandez said.

In all, she was held for about an hour and a half.

The Committee to Protect Journalists is investigating at least 280 cases of attacks on U.S. news workers since May 29, “a number we have never seen in the United States,” the group said in an open letter to mayors and governors. The L.A. chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists also sent a statement to local law enforcement leaders urging them to respect press freedoms. The organization also called on Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey to prosecute offending officers.

In a statement, Los Angeles Police Capt. Giselle Espinoza, a commanding officer in the Media Relations Division, said the LAPD was “committed” to protecting those freedoms.

“The relationship with the media is very important to the LAPD,” Espinoza wrote. “We have made extensive efforts to work with reporters ensuring not only their safety, but also their ability to cover this important story.”

The Sheriff’s Department said it also stood by news media protections.

“The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department strongly believes in the First Amendment and the right for our working press to safely cover events,” the department’s Information Bureau said in a statement.

But for Guzman-Lopez and others, questions remain. The images this year also recalled the so-called May Day melee of 2007, in which LAPD officers from the Metropolitan Division began attacking reporters and demonstrators, including families, after the customary May 1 festivities and rallies at MacArthur Park. After decades since the death of Ruben Salazar, have police agencies truly adopted a culture of protection for 1st Amendment rights?

“If you think about it, while I was being detained, I was unable to take photos, unable to report, so think about that information that was lost,” Helou Hernandez said. “You are hindering the press from doing their job, and from getting information out to people, so it’s incredibly dangerous.”

The officer who shot Guzman-Lopez has not been identified, said Arantxa Chavarria, a public information officer with the Long Beach Police Department. “Our chief of police, Robert Luna, spoke directly with Mr. Guzman-Lopez to express our apologies and to gain further insight into the circumstances of the incident,” she said.

“What was I doing to get shot at with a rubber bullet?” Guzman-Lopez asked. “Did the police officer miss? Was he aiming at someone behind me? Was he aiming at the African American man next to me? These people are pretty good shots, I suppose.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.