This county voted to recognize Black Lives Matter. Then it OKd 310 more Tasers

- Share via

MENLO PARK — As Bay Area communities adopt resolutions supporting the Black Lives Matter movement, one Silicon Valley county this week voted to stockpile its Sheriff’s Department with nearly $1 million in new Taser guns.

On Wednesday, the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors approved a budget that includes the purchase of 310 new Tasers. The approval of the Taser purchase is coming under fire, in part because it occurred just minutes after the board adopted a resolution supporting the Black Lives Matter movement.

“We have heard from our community and from protesters across the nation that enough is enough,” wrote Warren Slocum, the board’s president, in a statement posted on the county supervisor’s website. “We need to take concrete steps to address this injustice.”

In 2018, three unarmed people died after officers used Tasers on them within county limits.

By Friday evening, none of the five county supervisors could be reached for comment.

Video from a board meeting in early May, prior to George Floyd’s killing in late May in Minneapolis, shows the board approved the acquisition unanimously, and it was seen as a necessary expenditure required to replace the department’s aged, 15-year-old Tasers.

David Canepa, a supervisor for the county’s District 5, which includes South San Francisco, Daly City and San Bruno, said the expense was “a matter of common sense.”

The May vote came less than one year after county law enforcement officials revised their use-of-force policies, which included limiting the number of times a Taser can be used against a person to three and narrowing the justifications for use from “active resistance” to “causing immediate physical injury or threatening to cause physical injury.”

The new devices are considered safer than earlier versions, limiting the amount of time the Taser operates after it hits its target to five seconds, according to board minutes.

The department rejected recommendations by the American Civil Liberties Union to ban the use of carotid restraints, or chokeholds.

Across the San Francisco Bay Area, Black Lives Matter protests have erupted since Floyd’s killing on May 25.

In Oakland, nooses and effigies have been found hanging from trees, while state and local politicians are promising systemic reform and change.

In Menlo Park, a wealthy tech community on the San Francisco Bay Peninsula, the city’s chief of police retired abruptly during a virtual town hall meeting last week. He did so after listening to community members complain about his force’s racial profiling, alleged racism and his department’s cozy relationship with the social media behemoth Facebook.

“It’s confusing and crazy and totally not surprising,” said Faraji Foster, an artist and activist from East Palo Alto, referring to the San Mateo board’s votes and the chief’s retirement.

“The police have been terrorizing us for years,” he said while attending a Black Lives Matter demonstration in Palo Alto on Thursday night. “They don’t know any other way.”

Foster said the BLM movement calls for a reduction in law enforcement funding and police violence against Black communities and people. It also calls for investment in educational, recreational and senior care in Black communities.

“They say they support Black lives, but how can we believe it if they’re investing in more weapons for the police?” said Tenedra Julian, a resident of East Palo Alto, who was at the Thursday demonstration.

Palo Alto, part of Santa Clara County, has a median property value of $1.99 million and 56% of the population is white, 31% Asian, 4% Latinx, and just 1.2% Black.

In East Palo Alto, part of San Mateo County, the median home price is $600,200 and 60.7% of the population is Latino, 10.6% Black, 10.3% Pacific Islander and 8.9% white.

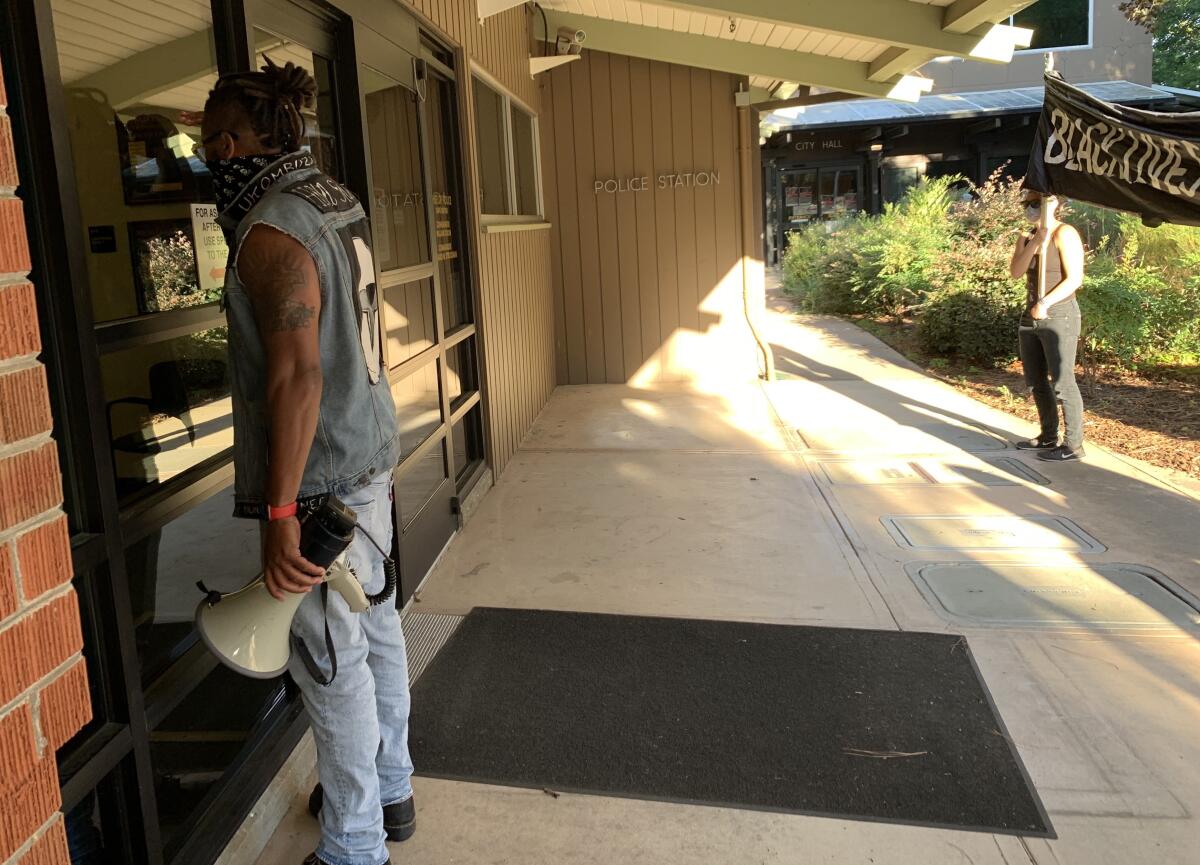

The demonstration, which started at Palo Alto’s City Hall, was convened by the Hood Squad, an activist group in East Palo Alto.

Hundreds of people marched north through the city’s streets to San Francisquito Creek, where they crossed into San Mateo County — passing through a thicket of dense redwoods and the memorialized 1769 campsite of Gaspar de Portola — convening in front of the city’s Police Department, where the demonstrators, led by Foster and Los Angeles rapper Milla, chanted, “Defund the police,” “Black lives matter” and “Hey hey, ho ho, these racist cops have got to go.”

Two police officers were seen leaving their patrol cars for the building. A few others were observed peeking out of the department building’s windows.

Income disparity in the Bay Area is higher than anywhere else in the state. According to an analysis conducted this year by the Public Policy Institute of California, residents in the 90th percentile of incomes earned $384,000 a year, compared with those at the bottom 10th percentile, who earned just $32,000.

The gap is striking as one drives from the west side of the 101 Freeway, in Menlo Park, to the eastern side, home to the city’s Belle Haven neighborhood and East Palo Alto. Or north along Middlefield Road from Atherton, which is one of the wealthiest ZIP Codes in the nation, to Redwood City.

Multi-acre estates, hidden by giant oaks, redwoods and magnolias, give way, almost immediately, to strip malls, car repair shops and abandoned industrial warehouses.

And for decades, the communities surrounding these wealthy enclaves have felt targeted by police, often afraid to venture too close.

“When I was a kid, East Palo Alto was considered the murder capital of the world,” Foster said. “Yet, I felt safer there than I ever did walking down the streets of downtown Menlo Park or Palo Alto.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.