‘More lemongrass, please’: Vietnamese home cooking and monthly meal services thrive during quarantine

- Share via

Mimi Truong took some time to scour Westminster’s T & K Food Market for ingredients to make her spicy beef salad (an in-demand dish among her 11 private customers), adding fresh mint, shallots, sprouts and crispy cucumbers to her cart.

Back in a makeshift kitchen in the garage of her rented home, she began whisking together fish sauce, lime juice and sugar in a small bowl, blending in salt, pepper, chile paste and lemongrass. Then she heated oil in a worn skillet and sliced the steak into thin strips before gently laying them in the sizzling pan and adding the vinaigrette.

As she worked, a radio blared with a message from a doctor, assuring seniors that the county vaccination schedule would proceed in an appropriate manner — that they would be protected. Soon, Truong’s phone rang with extra orders, asking for “more lemongrass, please,” so she scampered around her Garden Grove garage, opening more Styrofoam containers.

“My kids told me it’s time to retire. They say it’s not safe to keep going to the store. But I don’t know what else to do to earn an income,” said Truong, 66, who lives with her husband and his relatives. “I’m limited by language. And I actually like feeding people.”

Truong offers com thang, a meal service prepared by independent cooks or restaurant cooks, consisting of rice and savory dishes with a selection of broths. Her average meal costs $10; customers pay in cash.

While the coronavirus winds its way through Little Saigon and beyond, Vietnamese home cooking and monthly meal services are thriving. In Orange County, home cooks are supposed to apply for a yearly license via the county’s Health Care Agency. But enforcement is uneven and, like most street vending, selling com thang is typically part of an underground economy. Some cooks find legal loopholes but many reason that their enterprise is only temporary or that they’re satisfying an enormous need.

Kim Xuyen Ngo and her Westminster family of four are regular com thang customers. Depending on her cravings, she orders from different suppliers, choosing “things I never learned how to cook or are too labor-intensive, like egg rolls. Sometimes I look at posted pictures and email. ... It’s fast, easy, convenient.”

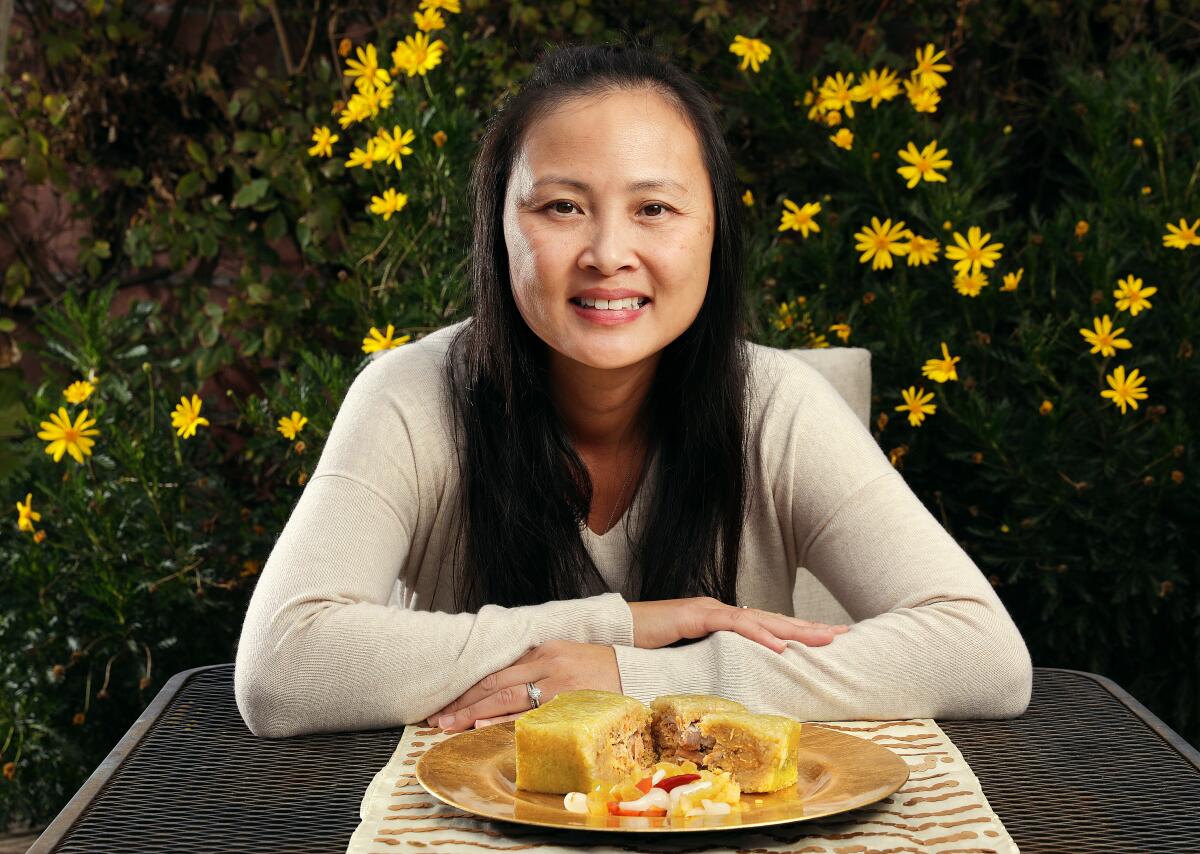

To get ready for festivities, when the lunar Year of the Ox unfolds Feb. 12, Ngo is sprucing up her house and buying the glutinous rice cakes known as banh chung, a seasonal staple. “The beauty of living where we live is you can take advantage of all the culinary delights around you,” said Ngo, a social worker with two young children. “I can spend more time with my kids and not have to worry so much about what we will eat.”

Ngo knows that “people have a question about if the food’s sanitized. I really believe these chefs put their whole heart into their cooking because a lot of time, they’re cooking for their families too.”

Catherine To, a UC Irvine graduate who wrote her master’s thesis on com thang and what she calls “gendered labor and the consumption of intimacy in the Vietnamese diaspora,” said she considers the service a “symbol of resilience.”

In the current economy, with prices for basic goods and groceries ballooning, home cooks “of course, make less profit, but they may want to prove themselves capable or to meet community needs, providing for those who aren’t able to care for themselves,” said To, who has a degree in Asian American studies. But, she cautioned, “To succeed at home, you really have to leverage your network. The only way to succeed is you have to have large orders.”

Some cooks have supplemented their earnings with side jobs, such as supplying face coverings. At the start of the pandemic, the shortage of affordable masks persuaded some to switch gears, sewing in their dining rooms and, when they couldn’t find enough retail fabric, scouting elastic and scrap material from family and friends.

Others started to give cooking lessons (Truong said she thought about it but concluded she doesn’t have the space), and some cooks make it a habit to share recipes and culinary adventures and advice online.

Ngoc Han Le is an administrator for Vietnamese Home Cooking Enthusiasts, a Facebook group that was created in 2019 and bloomed in the pandemic as more and more members isolated indoors. “During lockdown, people pass the time and reduce stress by cooking,” said the manicurist from Phoenix, who sees young people starting to try their hand with their elders’ recipes and non-Vietnamese cooks with a desire to whip up traditional meals.

“In this moment, people want to connect to those with interests like their own,” Le said. “They’re looking for support, they’re looking for friends, and they’re making friends in a larger circle.” The group has more than 71,000 members whose efforts to make dishes such as steamed tilapia with ginger and onions or fried fish laced in turmeric and dill are inspiring the photos and emoticons posted nonstop. “This is like a prescription; sharing can help us feel better when we cannot drive to Little Saigon like I do two or three times a year to binge on food,” she added.

To sees cooking as an antidote, a balm in a world ravaged by disease daily.

“There’s one basic reason why community members adjusted quickly, aiding each other in the face of COVID-19, Le said: “They’re always ready for a crisis because they’ve emerged from so much crisis.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.