Dine with history at L.A.’s landmark restaurants, founded in 1935 or earlier

- Share via

Is a restaurant worth a visit simply because it’s been around longer than that bottle of yellow mustard in your refrigerator? Longer than your oldest living relative? Maybe. Proper respect should be paid to an institution.

Los Angeles is home to restaurants celebrating a century in business. About 36,500 days in operation. The feat alone is something to marvel at.

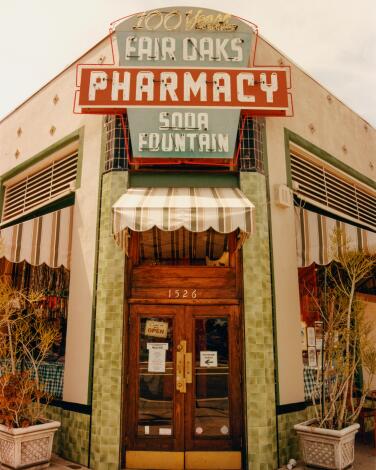

What is Hollywood without the martini culture built around Musso & Frank Grill? The Long Beach bar scene without the Schooners of cold beer and pickled eggs at Joe Jost’s? A South Pasadena stretch of Route 66 without milkshakes and phospate sodas at Fair Oaks Pharmacy? Over decades in business, these restaurants have become landmarks synonymous with the cities themselves.

Some of L.A.’s most popular attractions are our food halls, with Grand Central Market in downtown and the Original Farmers Market in Fairfax drawing millions of visitors each year. Grand Central Market opened in 1917 with nearly 100 food merchants. Its oldest running restaurant is Roast To Go, a walk-up counter that’s been around since 1952 and serves one of the best tacos in L.A.. In 1934, about a dozen farmers and other vendors started selling produce at the corner of 3rd Street and Fairfax Avenue, where the Original Farmers Market still operates today. Magee’s Kitchen, its oldest restaurant, began when Blanche Magee started serving lunch to the farmers in the ‘30s.

1. El Coyote founder Blanche March. (El Coyote) 2. The counter at Fugetsu-Do in 1904. (Fugetsu-Do Bakery Shop) 3. Alicia Mijares, left, daughter of Mijares founder Jesucita Mijares, with Maria Guzman in 1984. (Mijares Restaurant)

Many of the restaurants on this list were built by immigrants from every corner of the world, their American dreams realized in a mochi shop in Little Tokyo, a French restaurant in downtown L.A. and a taste of Jalisco, Mexico, in Pasadena.

If you’re looking for the oldest restaurant in Los Angeles County, you’ll find it in Santa Clarita, a city about 30 miles northwest of downtown. Originally called the Saugus Eating House when it opened as part of a railway station in 1886, the Saugus Cafe boasts a history rich with Hollywood film stars, U.S. presidents and a train network that helped establish towns across the state.

In 1916, the cafe moved across the street to where it sits now, one long, narrow building that includes a dining room and a bar. It has closed, reopened and changed hands numerous times over the last 139 years. Longtime employee Alfredo Mercado now owns the restaurant.

It’s a place that exists in a cocoon of nostalgia. The history embedded in the walls, the decor and the friendly staff are the main draw. If you’re searching for the best breakfast in town, you may want to keep looking.

The following are decades-old restaurants that have stood the test of time, shrinking wallets and fickle diners. In operation for 90 years or longer, these 17 destinations (listed from oldest to newest) are worth the trip for both the history, and whatever you decide to order. — Jenn Harris

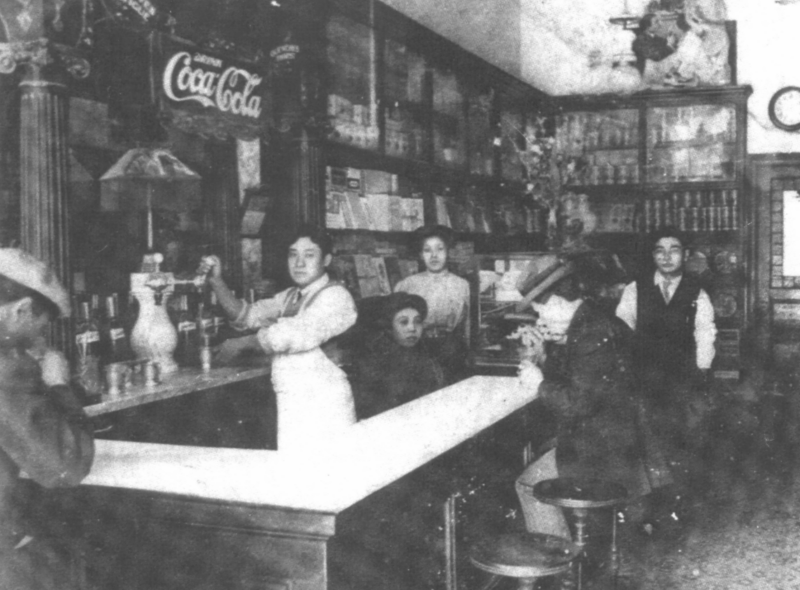

Fugetsu-Do, 1903

Behind the glass case in the tiny store, which is also crammed with shelves of Japanese snacks and rice crackers, are seasonal varieties of the filled mochi dumplings. In the springtime that includes kusa mochi made from the herb mugwort, and pale pink cherry-blossom mochi wrapped in the leaves of the tree. But the most popular is Fugetso-Do’s signature mochi topped with a fresh strawberry.

Cole’s French Dip, 1908

The 21st century iteration of Cole’s dip sandwich is your choice of roast beef, braised pork or lamb, or pastrami, served on a crusty roll lined with melted cheese (Swiss, cheddar, American or goat), an atomic pickle spear and a cup of au jus for dipping. Cocktails at the Red Car bar hew classic: an old fashioned, daiquiri, Manhattan, Irish coffee. During happy hour, add a Negroni to your dip for $7, “as mentioned in the Lincoln Lawyer,” the menu notes.

Philippe the Original, 1908

At Philippe’s second, current home — where it’s stood since 1918 — there’s vintage charm and vestiges of history everywhere you look: the antique wooden telephone booths you’ll pass near the entrance, the scattering of sawdust on the floor (a tradition of the restaurant), decades of articles and news clippings that date back to the start proudly displayed on the walls. Make your way through the zigzag of the queue to get to the counter, where staff carve roast meats, dunk crusty-exteriored French rolls into rich, meaty jus, and scoop hearty portions of salads onto plastic cafeteria trays. Opt for breakfast, magenta-hued pickled beets, or a rainbow of pies (some with meringue poised 2 inches over the filling), but a French dip of any meat is requisite for a first-time visit, as is the hot mustard. Pick up a bottle to bring the flavor of this icon home.

Fair Oaks Pharmacy, 1915

Musso & Frank Grill, 1919

On most tables are Musso’s famed martinis — stirred, not shaken, never with vermouth, and always served with “the dividend,” a mini carafe, or pony, of extra gin set into a diminutive ice caddy so that you can top off your sensibly sized glass and ensure your cocktail stays chilled as long as it lasts.

Executive chef J. P. Amateau (fittingly, a onetime Hollywood stuntman) and the restaurant’s team of kitchen pros have brightened and streamlined the menu established by original chef Jean Rue while maintaining key classics. I miss the lamb chops hot off the grill and finnan haddie (smoked haddock), but if you ask, you can still get hearts of romaine with a side of Roquefort vinaigrette. The sand dabs and creamed spinach are as good as ever, Jonathan Gold’s favorite Welsh rarebit remains on the menu and though Musso’s is no longer open during the day, flannel cakes, paper-thin and with a flavor reminiscent of fortune cookies, make a fine dessert.

As for the name, the Musso was Joseph Musso and the Frank was Frank Toulet. But at first there was only Toulet, who on Sept. 27, 1919, opened Frank’s Cafe on Hollywood Boulevard. Musso came along in 1923 and added his name to the enterprise. In 1927, John Mosso and Joseph Carissimi bought the place and later moved the restaurant one door down to its current location. So we might be talking about Mosso & Joseph if the two had wanted their names immortalized.

Mijares Mexican Restaurant, 1920

One of the underappreciated pioneers of California’s classic Mexican food is Jesucita Mijares. She came to the U.S. from Jalisco, Mexico, and in 1920 opened a tortilla and tamale business called Jesucita’s from her home on Pasadena’s Fair Oaks Avenue. She quickly started serving tacos, enchiladas, chilaquiles, tostadas and other Mexican dishes, using a stone grinder for the masa in place of her metate when demand increased. Her mole and other sauces were especially prized and her reputation as a cook grew. In 1949, she moved the operation, renamed Mijares, to the corner of Palmetto Drive and Pasadena Avenue. Since then, the sprawling, hacienda-style restaurant, which can seat more than 600 customers and has four patios, has been a gathering spot for family celebrations and couples wanting a relaxing night out. Paul McCartney is often mentioned as a Mijares fan.

Over the years, the menu has evolved. One recent weekend special was pescado primavera (grilled mahi mahi from Fish King with tomato-cilantro butter over asparagus), and the margarita and other cocktail variations are vast. On my most recent visit, I went for a blood orange margarita on the rocks, which our pro waiter offered with both salt and Tajín on the rim, plus the classic Platillo Mexicano — a tamale with nice chunks of pork, a chile relleno with the kind of fluffy batter that home cooks rarely achieve and a cheese enchilada. It was perfect Mexican comfort food.

The Derby, 1922

Tam O'Shanter, 1922

El Cholo, 1923

Credited with introducing now-iconic Mexican American dishes such as burritos to American palates, El Cholo remains a family affair with Ron Salisbury — Aurelia and George’s son, now 92 — at the helm. With six locations across L.A. (and a newly opened seventh in Salt Lake City), much of the staff has been in place for decades. Rosa’s recipes still anchor the menu, with sensible adaptations that reflect diners’ shifting tastes, such as red-sauced enchiladas with more chiles for a less mild take. The menu lists the date that each item was added so you can travel back in time with traditional albondigas and chile con carne, or try updated favorites including sizzling fajitas (1984) and pan-seared mahi mahi tacos (2001). The house margarita has been around since 1967 and is served on the rocks in a pint glass, but I prefer the blended coconut marg that’s rimmed with toasted coconut.

Joe Jost's, 1924

Its founder — a Hungarian barber, outdoorsman and future restaurateur — dreamed of immigrating to the U.S. and, at 16, he finally did. Eventually Jost traded his barber’s shears for an early iteration of his bar, first launching Joe Jost’s in Newport Beach with ice cream, beer, billiards, poker and candy. In 1924 he opened his business again, this time in Long Beach as a combination barbershop and pool hall with plenty of poker. When Prohibition lifted, Jost integrated beer into the offerings and with it, a food menu of sandwiches and those now-iconic pickled eggs. In order to avoid any alcohol-induced haircuts or injuries, Jost replaced his barbershop chairs with booths, which are almost constantly filled today.

Bay Cities Italian Deli & Bakery, 1925

Barney's Beanery, 1927

L.A.’s original location might be the most iconic but there are others in Santa Monica, Burbank, Pasadena, Brentwood and even LAX, each with their own programming and unique craft beer lineups. At the oldest outpost, vintage Harley Davidson bikes displayed as decor cordon off the dining room from the bar and there are TVs in nearly every corner. There’s a soft red glow cast from Coor’s-brand lamps, which hang over tables decoupaged with photos and newspaper clippings of celebrities. On one wall there’s a framed check from Marilyn Monroe, written to cover her tab 75 years ago. Barney’s is an iconic greasy spoon steeped in sometimes even greasier history, a mainstay during the Sunset Strip’s sleaziest decades and located just a short jaunt from legendary venues such as Whisky a Go Go. Long may the scene reign.

Taix French Restaurant, 1927

Eastside Italian Deli & Market, 1929

They introduced hot food to the sandwich menu, adding a stove that allowed for eggplant parmigiana, lasagna and sausage with peppers. Both the recipes and the owners became community fixtures, and while these brothers passed on, their legacy is alive and well. The next generation of Angiuli brothers still serves their same recipes, heaping soft, gargantuan rolls with cold cuts, house-made red sauce draped over pastrami and sausage, and more modern specials like a “The Bear”-inspired take on the Chicago Italian beef sandwich. All walks come through Eastside Italian Deli, but it’s especially popular on Dodger game days, given its proximity to the stadium. Grab some cannoli while you’re at it.

Canter's, 1931

Now run by the third generation of the Canter family, the late-night diner remains as reliable as ever, attracting celebrities, tourists and locals with its Art Deco-inspired interior and classic Jewish American staples such as corned beef hash, pastrami sandwich and matzo ball soup. Next door, the Kibitz Room is a dive bar that hosts karaoke and live bands. Note that takeout is available 24 hours but dine-in is from 6 a.m. to 11:30 p.m. on weekdays and becomes 24 hours from 6 a.m. on Saturday through Sunday night at 11:30 p.m. No matter what you get, stop by the bakery for chocolate chip rugula on the way out.

El Coyote, 1931

The menu features crowd-pleasing Mexican American standards, including nachos, burritos and a fajita plate. For me, it’s the house margarita and storied surroundings that make this classic haunt a must visit.

Cielito Lindo, 1934