Amid new revelations, Alex Odeh’s assassination in O.C. remains unsolved

- Share via

On the morning of Oct. 11, 1985, Santa Ana Police Officer Hugh Mooney received an urgent call from the department’s watch commander about a bombing. Around 9 a.m., a thunderous blast demolished the second story of an office building on 17th Street and left one man, Alex Odeh, critically injured.

Mooney sent homicide investigators over to Western Medical Center in Santa Ana, where doctors desperately tried to save Odeh’s life.

“The information I had was that he had a traumatic amputation of one of his legs,” said Mooney, who hasn’t spoken publicly about that day until now. “It didn’t look good for him. I wanted to get a dying declaration if one was available.”

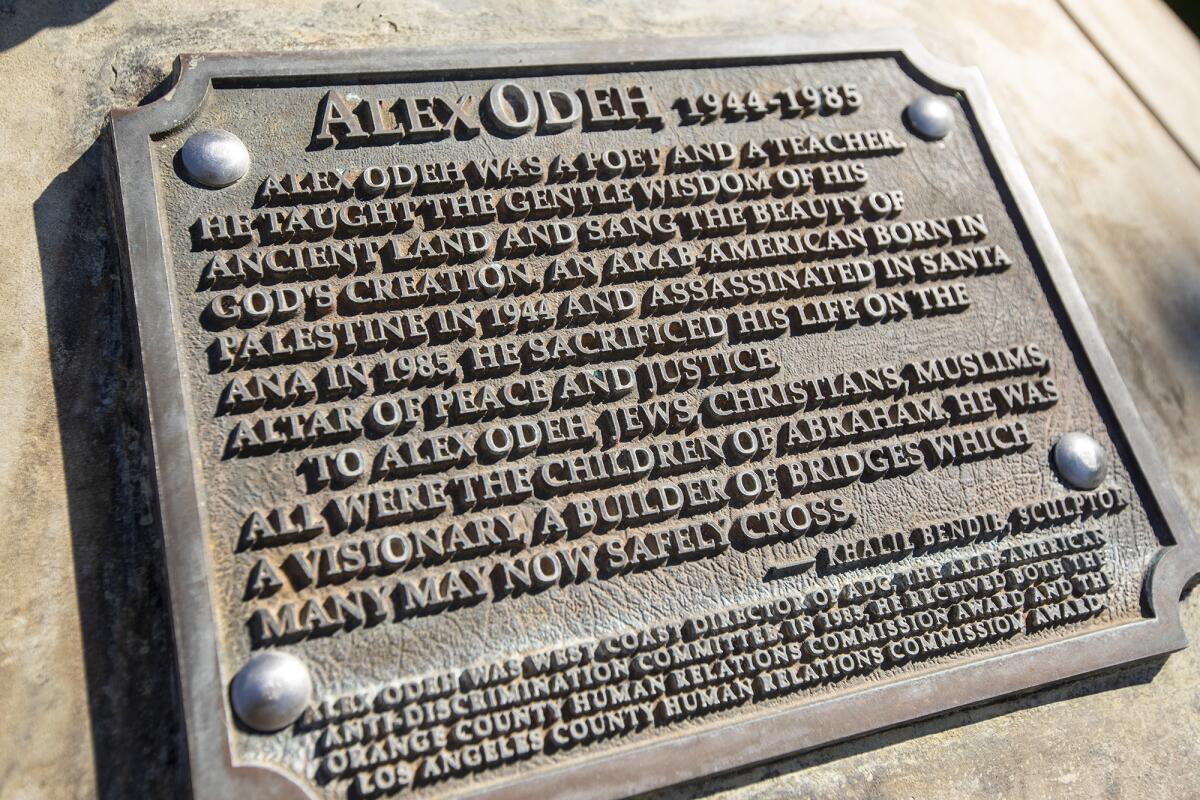

But Odeh, a Palestinian American activist, never regained consciousness and died two hours after a rigged pipe bomb detonated when he opened the door to the Santa Ana office of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. Odeh served as West Coast regional director of the civil rights organization formed in 1980 to combat anti-Arab stereotypes in U.S. media while promoting balanced reporting on Middle Eastern affairs.

A deputy chief assigned Mooney to manage the crime scene; he didn’t know it at the time, but “Area B,” the police-designated section of the city he commanded, became a smoldering site of a seemingly far-removed Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Santa Ana police and the city’s Fire Department established a command center at an office across the street. About 20 minutes after taking control of the scene, Mooney noticed a helicopter hovering overhead before it landed on a vacant lot.

Four men exited the chopper.

“These guys come out and they come walking over to us — a couple of FBI agents and a couple of LAPD Joint Terrorism Task Force members,” Mooney said. “They told us that they had been tracking a couple of guys from New York out to Los Angeles and they lost them at LAX. They were probably responsible for the bombing. At that time, they gave us two names.”

An anonymous “police official,” which Mooney says wasn’t him, previously disclosed similar details to Village Voice reporter Robert Friedman more than 30 years ago, an account that disclosed the names of Andy Green, Robert Manning and Keith Fuchs.

Mooney recalled being told about Manning and Fuchs.

The three men belonged to the Jewish Defense League, an extremist group founded by the late Rabbi Meir Kahane that the FBI initially suspected of carrying out a series of bombings that year, including in Santa Ana. A month after Odeh’s killing, FBI spokesman Leon Bonner publicly attributed the attack to the JDL — a claim that disappeared from all future comments made by the agency.

The case remains open and unsolved 36 years later, with the FBI having never publicly named suspects despite the immediate intelligence Mooney says he received at the scene.

Without arrests, every anniversary since the bombing has become a ritual of frustration for the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, known as the ADC, as it continues to press for answers and accountability. In 1986, Rep. John Conyers, a Michigan Democrat, chaired a congressional hearing on Odeh’s assassination. Ten years later, the Justice Department and the FBI announced a $1-million reward for information leading to a conviction in the crime.

The case continues to grow colder by the day despite all efforts.

Ahead of the Alex Odeh Memorial Conference this weekend in Garden Grove, the ADC is again asking questions, this time of a new White House administration. The group feels more optimistic with U.S. Atty. Gen. Merrick Garland at the head of the Department of Justice.

“If any attorney general over the past 36 years should have a deep-rooted understanding of the importance of prosecuting these cases, it’s him,” said Abed Ayoub, ADC’s National Legal and Policy Director, citing Garland’s past as a federal prosecutor in the Oklahoma City bombing.

The ADC is demanding Garland make public the names of any suspects and their whereabouts along with other key details of the case.

Manning is considered a person of interest in the case, and his location is well-known. He’s serving a life sentence at the Federal Correctional Institution in Phoenix.

After Manning was extradited from Israel in 1993, a jury convicted him for a mail-bomb murder that killed a Manhattan Beach secretary in 1980. During the Obama administration, the Justice Department took an extraordinary step in 2016 and recognized the ADC and the Odeh family as Manning’s victims.

“It’s kind of a paradox where they recognize us as a victim but they haven’t charged him with the crime that they recognize us of being a victim of,” Ayoub said. “What’s the holdup?”

The internal classification cleared the way for Helena Odeh, Alex’s eldest daughter, and Samer Khalaf, ADC president, to speak at Manning’s parole hearings in 2018 and 2020.

In addition to the campaign for justice, a proposed resolution from Rep. Lou Correa (D-Santa Ana) seeks to memorialize Odeh as a matter of record. On Sept. 30, he introduced HR 695, which expresses “profound sorrow” over his death as a victim of domestic terrorism. It recounts Odeh as a poet and a lecturer at Coastline College in Orange County in addition to his ADC activism.

“This is a man [who] was murdered, it would appear, because of his anti-discrimination activities,” Correa said. “This is something that is not tolerated in America.”

Michigan Democratic Rep. Rashida Tlaib, the first Palestinian American woman ever elected to Congress, co-sponsored the resolution. Correa hopes that more of his House colleagues do the same, not just as an act of remembrance but also to renew interest in the investigation. He plans a House floor speech in that effort.

“This is a cold case, and in murder there’s no statute of limitations,” Correa said. “We want to find out what happened. There’s a lot of allegations. It becomes even more critical what the answer is given our concern with domestic terrorism.”

More than a decade passed before Mooney got another close — and final — look at the Odeh case. In 1996, he accompanied Santa Ana Police Department homicide Det. Ferrell Buckels as they traveled to the FBI’s Los Angeles office for an hourlong meeting about it.

Alongside Buckels, the lead Santa Ana police investigator on the case, Mooney recalled being seated at a table with FBI agents, New York Police Department officers and a State Department official.

The FBI appeared frustrated with the prospects of prosecution. Earlier on, they allegedly enjoyed some cooperation with Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security service, in the effort to locate Green and Fuchs, both long rumored to have lived in Kiryat Arba, an Israeli settlement near the West Bank city of Hebron.

But after the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in November 1995 by an Israeli right-wing extremist, the working relationship cooled. The Arab League briefly arose as a possible alternative at the meeting. According to Mooney, the State Department official intervened around that time with a lecture about the “bigger picture” of international relations.

“That was the end of it,” Mooney said.

The FBI, citing the ongoing 36-year-old investigation, declined to confirm or deny Mooney’s accounts from the scene in 1985 or the 1996 meeting.

Both Santa Ana police officers left the FBI office that day feeling like their time had been wasted.

Buckels “was visibly upset when we were coming back,” Mooney said of the long ride home. “His idea of the law was that the law is the law, regardless of who you are.”

Later that year, Buckels retired from the Santa Ana Police Department. He died in 2017. Nobody on the force is currently assigned to the Odeh case.

Mooney retired as a lieutenant in 2002 and is transparent about the case’s gaps, too: According to him, no witnesses were interviewed, no surveillance footage existed, nor were any fingerprints found at the scene.

How the bomb made its way to Santa Ana before being planted remains a mystery.

For all questions left unanswered, Odeh, a local resident, husband and father of three daughters, was assassinated and the investigation languishes on — not for an apparent lack of leads.

“It was a very solid case and easy to prosecute,” Mooney said. “I feel really sorry for the family, especially the kids. They were so young. [Odeh] was a good man — a man of peace.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.