- Share via

SAN DIEGO — Imperial Beach surfers and swimmers have long complained about foul odors along the city’s shoreline during summer months. For years, those concerns were swept aside as the Mexican sewage plaguing the town rarely spills over the border through the Tijuana River unless it’s raining.

A new report out of UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Stanford University and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency now confirms what many have suspected: A crumbling wastewater plant south of the border is daily discharging millions of gallons of raw sewage into the ocean that routinely carry pathogens up the coast.

“I’m embarrassed to admit [it], but we used to get complaints from surfers along Imperial Beach when there would be these strong northward currents,” said Doug Liden, EPA environmental engineer and co-author on the paper. “We’d think, ‘Six miles south of the border, that’s a long way for wastewater to travel.’”

The study, published in the American Geophysical Union journal GeoHealth, found that thousands of beachgoers in the city, particularly in the summer, are likely contracting norovirus through untreated wastewater. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, headache and diarrhea.

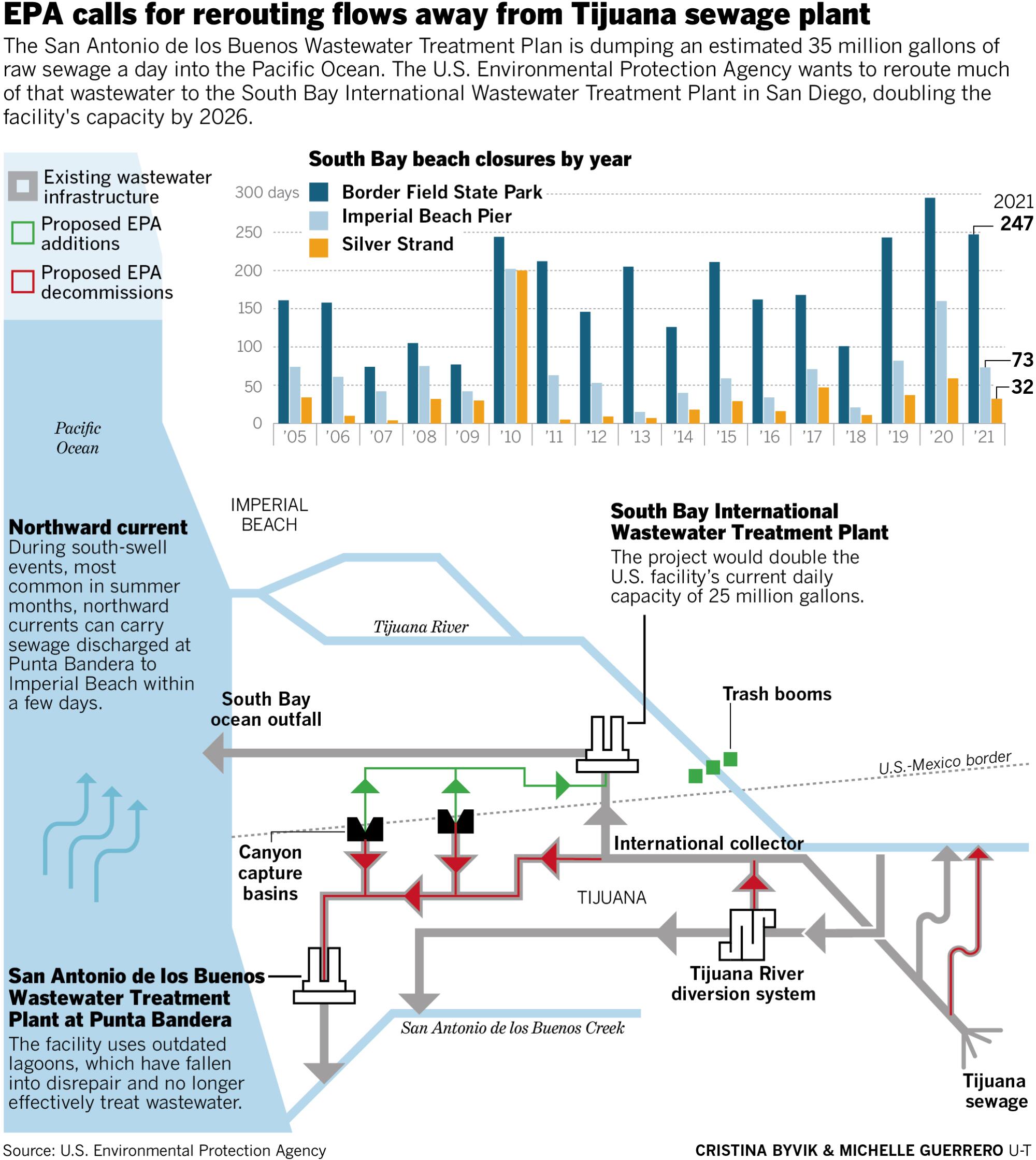

While some of those pathogens come through the Tijuana River — especially when rain and sewage spills overwhelm a diversion system that otherwise sucks flows out of the concrete channel — the lion’s share of illness during summer months can be traced back to discharges from the San Antonio de los Buenos Wastewater Treatment Plant in Punta Bandera, Mexico, according to the study.

“We saw with our own eyes: You pump in dye, and it’s rapidly transported along the coast,” said Falk Feddersen, the study’s lead author and hydrodynamics expert at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “They’re putting in 35 million gallons a day of essentially raw sewage.”

Baja California’s top water officials have acknowledged that the more than 30-year-old plant is in disrepair and spewing untreated wastewater into the ocean. They’ve said a rehabilitation project is going out to bid this year.

However, U.S. officials aren’t waiting for Mexico to replace the facility. The UCSD study was undertaken specifically to inform a major EPA initiative aimed at overhauling wastewater infrastructure along the border.

Congressional leaders secured $300 million in late 2019 to help address the issue, under the United States-Mexico-Canada trade agreement. Since then, the EPA has workshopped several concepts for spending the funds, with the overall goal of reducing beach-closure days in San Diego’s South Bay.

After reviewing the recent study, federal and local officials prioritized efforts to reroute much of the wastewater currently pumped to Punta Bandera. Instead, that sewage would be sent to the South Bay International Wastewater Treatment Plant along the border in San Diego. The facility uses a more modern treatment technology compared with the plant at Punta Bandera, which relies on a system of outdated lagoons.

“It used to be the theory as long as we kept those flows in Mexico, it didn’t matter what happened to them,” said Liden with the EPA. “Thanks to the Scripps study that’s been shown clearly not to be the case. We really have to treat the flows before they reach the coast.”

The project, which would double the U.S. facility’s current daily capacity of 25 million gallons, could be completed as soon as 2026, according to the EPA. The new system should also help Baja save on pumping costs since the treatment plant in San Diego is at a lower elevation than Punta Bandera.

A second phase of the roughly $630-million blueprint, which still requires additional funding, would focus on building another treatment plant in San Diego to take flows from the existing diversion system in the Tijuana River. As part of that effort, another intake in the channel would be built north of the border to catch flows that overwhelm Mexico’s pumps.

Imperial Beach Mayor Serge Dedina welcomed the report and the new vision.

“This is all a sea change from six years ago, when there was almost no acknowledgement of what was coming out of Punta Bandera,” he said.

Part of the issue can be chalked up to limitations in water-quality testing, which don’t identify norovirus specifically but human fecal bacteria known to carry such pathogens.

Feddersen of UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography said that bacteria can break down under sunlight as the sewage makes its way up the coast, a journey that can take two to three days. As a result, testing often comes back negative even when pathogens persist.

“There are many things that can be in sewage that can be really bad for you, but the reason why norovirus is particularly troublesome is because in seawater it likes to live for a long, long time,” he said.

San Diego County’s Department of Environmental Health and Quality monitors water quality, determining when beaches should be closed and warning notices posted. Since 2019, it has conducted daily water-quality testing at several locations from the border up through Imperial Beach and Coronado. Officials said results usually take about 24 hours.

The county expects to roll out a new rapid-testing technology this year that would provide results within eight hours or less. Having already secured EPA approval, it probably will be the first such agency in the nation to use the method.

Lifeguards in Imperial Beach said they have another way of bracing for summertime pollution. They monitor ocean and wind conditions, looking for northward currents, often called south swells.

“If you get south swell with a south wind, we’ll probably be shut down in the next couple days,” said Jason Lindquist, captain of lifeguards at Imperial Beach. “It’s pretty fast.”

Lindquist said that while people have known for years about the summertime pollution, attitudes have recently started shifting.

“It used to be, ‘I grew up here. I’m immune,’” said the Imperial Beach native. “Nowadays, more and more people are reporting that they got sick.”

Union-Tribune reporter Wendy Fry contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.