They say California stole their ancestors’ land. But do they qualify for reparations?

- Share via

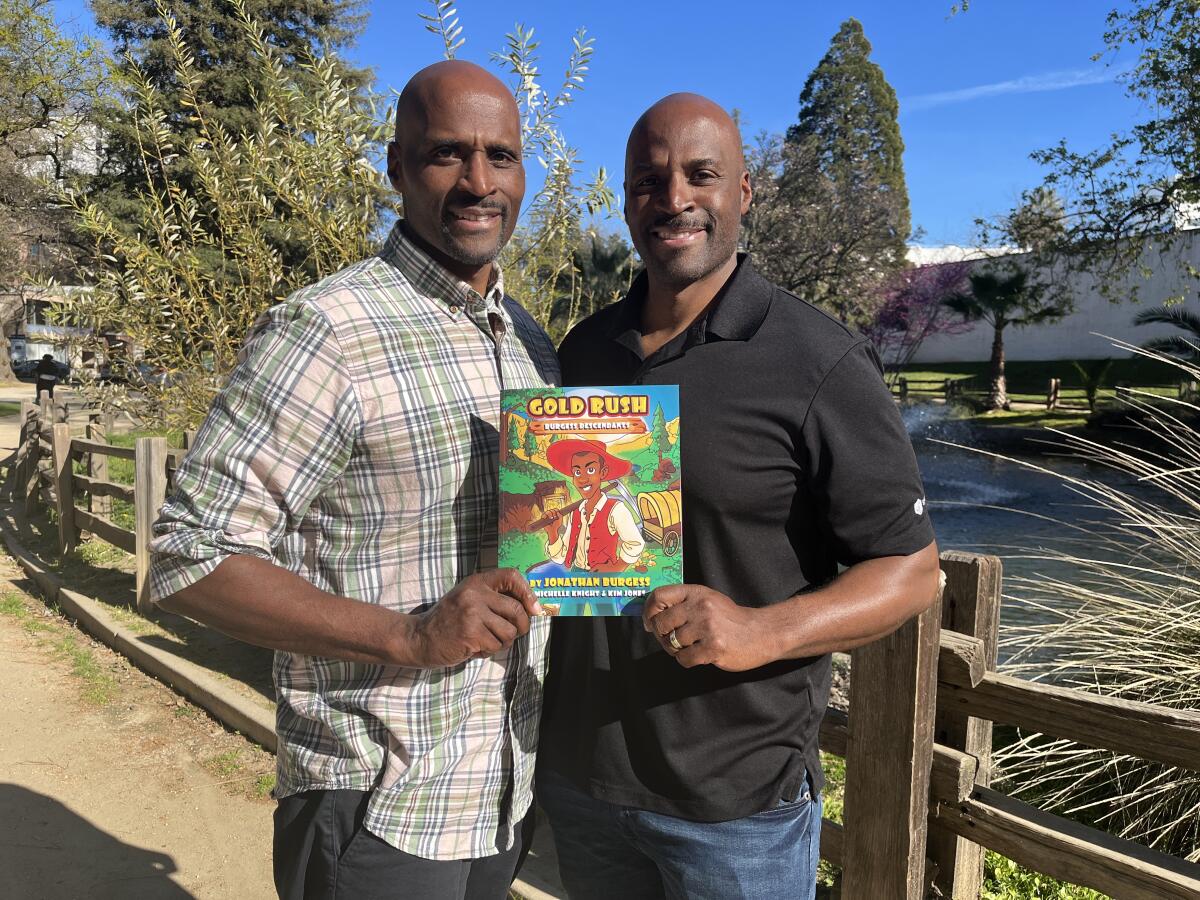

SACRAMENTO — Jonathan and Matthew Burgess had a story — well, a truth — to tell, and they wanted to tell me at Sutter’s Fort State Historic Park.

It seemed appropriate.

Like many a Sacramentan, the twin brothers had walked through the preserved stone buildings, dirt paths and old trees as schoolchildren. It’s where they learned about John Sutter, the pioneer who founded what would become California’s capital city and who controlled land 45 miles away in Coloma, where an employee named James W. Marshall discovered gold in the American River, starting the Gold Rush.

Or so the whitewashed story goes.

The Burgess brothers insist the truth — based on old records, photos and stories passed down from generation to generation — is a lot more complicated.

They say that it wasn’t just Sutter who had land in Coloma. Free Black people did, too, including their formerly enslaved ancestors, before it was unfairly seized by the state. For that, the brothers say their family is owed reparations.

“If there were descendants of Sutter right now, talking about this ground that we’re on and how it was taken from them, would we be having this conversation?” Jonathan fumed as Matthew, digging his heels into the dirt at Sutter’s Fort, nodded in agreement. “Or would their land already have been given back to them?”

I understand the brothers’ frustration.

Back in September, Jonathan was one of the first people to turn his story into official testimony before California’s Reparations Task Force, which is investigating and recommending remedies for the history of injustice against Black people.

Those were heady times. Gov. Gavin Newsom had just signed a bill to return a swath of oceanfront property in Manhattan Beach to a Black family that lost it through another racist act of eminent domain. Anything seemed possible.

Since then, though, the brothers have gotten bogged down in the bureaucratic realities of reparations, as the governor has moved on and the task force has taken the lead on the issue. And now the Burgess brothers’ case has been pulled into the most important policy question that the task force has tackled to date — the question of eligibility.

If California does decide to pay reparations, who should get it? All Black people? Or only Black people who can trace their lineage to chattel slavery?

A lot is riding on the answer. That’s probably why, even after two hours of heated debate, the task force couldn’t come to an agreement last month. They postponed a vote until their next meeting later this month.

Meanwhile, Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D-Los Angeles) has introduced a bill that would give the task force, of which he is a member, another year to do more research and finish its work.

“We need to not just hear from the American descendants of slavery,” he told me. “We need to hear from every African American if we can.”

The Burgess brothers are upset. And impatient. It’s obvious, they say, that lineage should determine who is eligible for reparations.

“I don’t know why it’s such a big question. We can’t expect California to solve the problem of racism,” Jonathan said. “That’s always existed. It will continue to exist. There’s nothing we can do about that. But what we can do is we can make some fundamental repairs to the foundational people that built this country, built this state and had everything taken away.”

I wish I was as convinced.

::

As far as I know, some of my ancestors were enslaved. That’s what my oldest relatives recall being told by their oldest relatives anyway.

Most of my family, from what I’ve heard, hails from Mississippi and Alabama. Which towns and cities? Other than Sardis, Miss., I have no clue. Names and exact relations also have been largely lost to history.

This sort of guesswork is pretty common for Black Americans. Even with genealogy kits and the internet, inaccurate and nonexistent public and private records complicate efforts to track our lineage. I found this out while trying to trace my great grandmother’s relatives in New Orleans. I came away with nothing.

The Burgess brothers are different, though. They can recount, with almost encyclopedic detail, the history of their family going back almost 200 years.

“We came from a family that could read and write. That was a privilege,” Matthew told me. “And that was something that allowed us to put the pieces together because of the writings that they left behind for us, in addition to the oral narratives that our mother had provided.”

They were taught “even the history that wasn’t taught in school,” Jonathan added.

Most lessons started with trips to Coloma, a small town in El Dorado County not far from Placerville, where a good percentage of residents still want a noose to be the city’s symbol and “hangtown” to be its nickname.

With high housing prices driving people inland, a deep-seated fear has taken root in pockets of red California that they’re being invaded by liberals.

The brothers say their great-great grandfather, Rufus Burgess, was brought to Coloma in the mid-1800s as a slave. Eventually, he was able to save enough money to buy his freedom and send for his son, Rufus M. Burgess, and purchase a home.

Deeds and other records indicate the family owned several properties there, including an old church and a blacksmith shop.

The brothers say additional acres that belonged to their ancestors sit across the American River from where Sutter ordered Marshall to build a sawmill before finding gold.

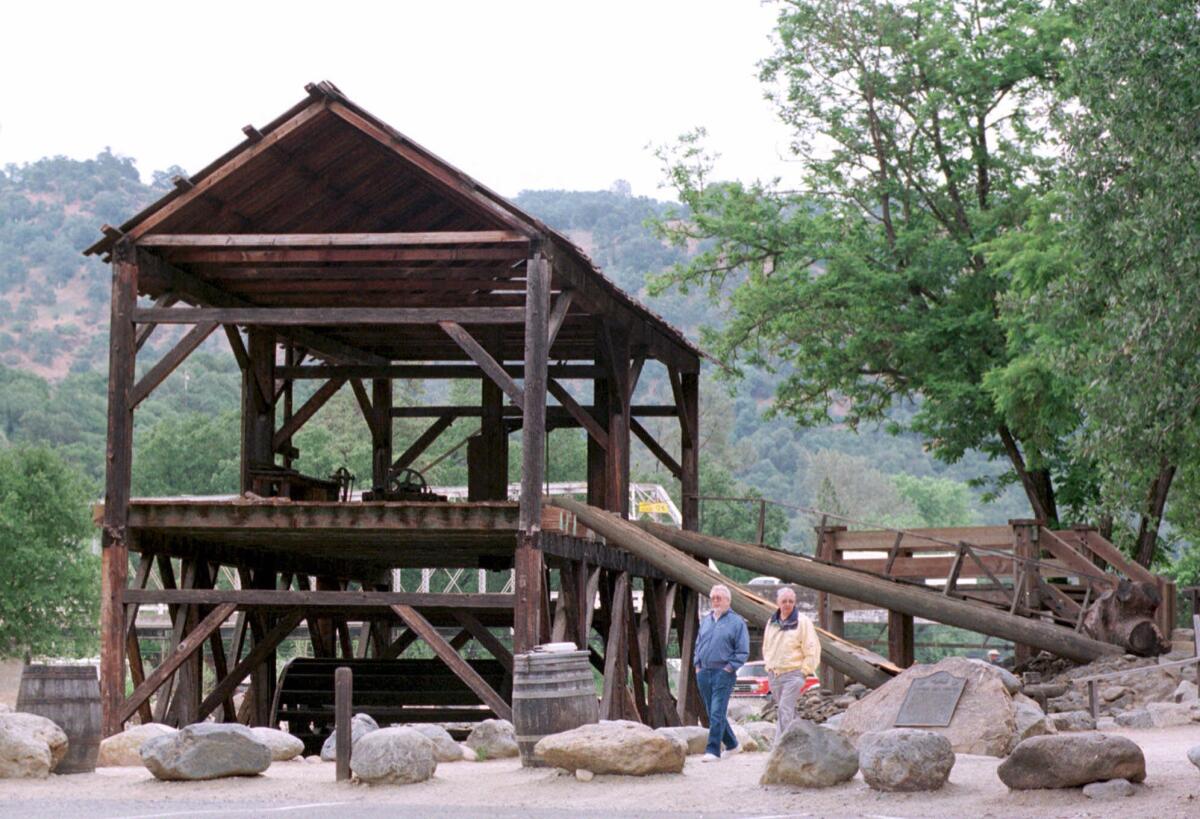

Today, most of that land — indeed most of Coloma — is part of Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park, a tourist-ready collection of Gold Rush-era businesses, churches and cemeteries, surrounded by a handful of private residences.

To build the park, the state took the land by eminent domain. Rufus M. Burgess Jr., the brothers’ grandfather, was among the last of his line to live in Coloma. The rest of the family had little choice but to relocate to Sacramento, where Jonathan is now a firefighter and Matthew is a cop.

Of course, not everyone believes the brothers or their evidence. Many point to Nancy and Peter Gooch as their main reason for skepticism.

As historians have long told it, a white man named William Gooch brought the Black couple to Coloma as slaves in the mid-1800s. Their son, Andrew Monroe, eventually joined them, and according to their descendants, they collectively owned hundreds of acres of land before the state took it all by eminent domain to build Marshall Gold Discovery park.

The Burgess brothers don’t doubt that Nancy and Peter lived in Coloma. They just believe that the Burgess family and the Gooch family were mostly the same people.

“Our paperwork says Nancy Gooch was our great-great-grandmother. But we don’t call her Nancy. Her name’s Annie,” Jonathan explained. They were “ridding themselves of their slave names.”

Where the federal government has failed, California enacted new laws that will finally address police misconduct and set an example for reparations.

Sorting out the truth from the well-worn stories of history will be a tough task. That’s one reason the brothers are working with Kavon Ward, the Los Angeles activist who helped persuade Newsom and the California Legislature to return that oceanfront property in Manhattan Beach to the Bruce family.

But this case, with its competing and overlapping claims to a specific lineage of formerly enslaved people in Coloma, illustrates why the question of eligibility for reparations can be so hard to answer.

“Anybody can say that they’re descendants of slaves. But how do you prove that? How do you validate that?” Jones-Sawyer asked. “How do we make sure that those who are most aggrieved, which are descendants of slaves, that they get the proportional amount of money they should get for that grievance?”

::

I’m all for reparations, but I fear there will be unintended costs.

There’s no doubt that using lineage as a prerequisite for distributing cash or land would be the safest, most legally viable option for California. Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of UC Berkeley’s School of Law, told the task force as much during a recent meeting.

Secretary of State Shirley Weber, who authored the bill that created the task force, also has made it known that this is her preference. “If we decide to solve all of the problems around the world, we will probably get 50 cents each,” she said. “This is about ... what the U.S. owes those individuals who built this country.”

But while reparations done this way will certainly make some Black families whole, the whole of the Black community — and its only-in-California multicultural kumbaya-ness — will almost certainly be torn apart. At least for a time.

On one side, there will be people who can prove they are the descendants of slaves. On the other side, will be people who cannot. Those who, for example, know very little about their families, or can’t afford a genealogy test for proof or are wary of government building a database of DNA. I can already imagine the conspiracy theories.

Then there will be the Black immigrants and the biracial Californians whose ancestors were slaves, but who have always identified as white. I’m really not looking forward to “Black enough” litmus tests.

And yet, expanding eligibility to cover all Black people in California carries a cost, too — namely a legal one. Reparations distributed based on race likely wouldn’t stand up to a court challenge, especially given the majority conservative U.S. Supreme Court.

Still, it’s hard to ignore what several task force members have said about the importance of addressing the harm being done to all Black people, regardless of their ancestry.

Discriminatory housing practices that have left a disproportionate number of Black people penniless and homeless. A biased criminal justice system that has led to over-incarceration and too many fatal shootings by police. And health inequities that have caused far too many deaths from COVID-19.

“This is what reparations is really about,” insisted Jones-Sawyer, whose uncle was part of the Little Rock Nine. “That we finally come to grips with systemic racism, the biggest crime that this country has ever done.”

Given all the back and forth, the Burgess brothers feel like they are fighting their own fight. So they keep telling their story — their truth — most recently in a children’s book, “Gold Rush: Burgess Descendants.”

They don’t want to wait years for the task force to decide if they are eligible for reparations and, if so, under what conditions. They want Newsom to return their land in Coloma immediately and to write them a check out of the state’s bulging budget.

“It was our ancestors that were here as foundational people who paved the way, and those people were not able to pass on generational wealth to their descendants,” Jonathan said. “That lineage thing is very important. It’s powerful.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.