‘Meeting with the enemy’: Was the leader of the Mongols motorcycle gang a double agent for the feds?

- Share via

Drunk and despondent, David Santillan called his wife to beg for forgiveness.

The president of the notorious Mongols motorcycle club promised he’d put his infidelities behind him, get sober and be a better father to their children.

Then the conversation, which she was secretly recording, turned to John.

“John told me already — I have one year,” Santillan said. “One year, he’s retiring ... and he can’t protect me. He told me. So we have to have an exit strategy.”

“John” was John Ciccone, an agent with the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives who had investigated the Mongols for decades.

Livid at her husband — and the fact that his mistress had been harassing her and her children — Annie Santillan texted the June 2021 recording to two members of the Mongols. Her husband, she wrote, “has been working with the government [this] entire time.”

“He is simply a CI,” she wrote — a confidential informant. “Or in other words, he is a rat.”

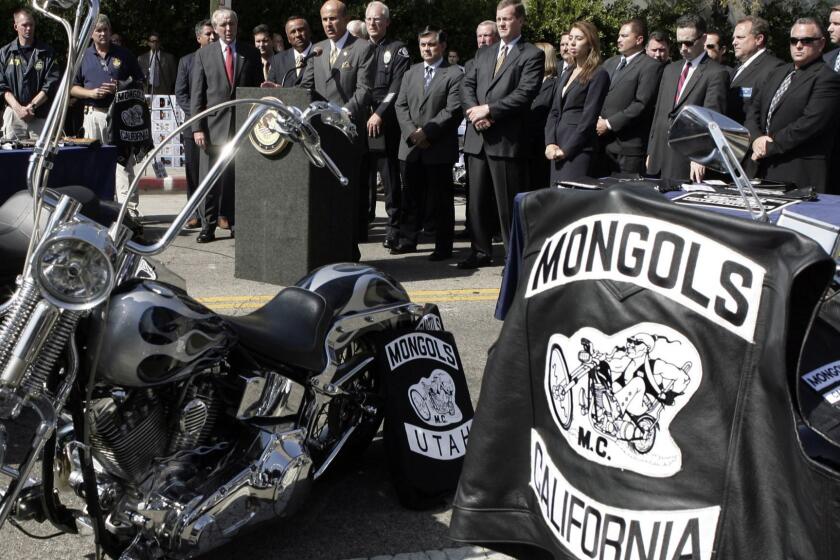

A federal judge Friday slapped the Mongols motorcycle club with a sizable fine and probation as punishment in a racketeering case, but rebuffed another attempt by prosecutors to strip the notoriously violent group of trademarks it holds on its logo.

It was an explosive claim. Three years earlier, a federal jury had convicted the Mongols of racketeering, finding that the group was a criminal organization whose members had beaten and killed rivals and trafficked in drugs.

Now, here was evidence suggesting that their leader had a secret relationship with the agent who led the investigation.

Attorneys for the group asked U.S. District Judge David O. Carter to set aside the jury’s verdict, which had sent no Mongols to prison but cost the club a $500,000 fine. As “a mole in the defense camp,” they claimed, Santillan had shaped the Mongols’ trial strategy in ways that helped prosecutors and passed inside knowledge of it to Ciccone.

Carter, who oversaw the trial, ordered the two sides back into his Santa Ana courtroom recently for a hearing to determine what, if any, relationship existed between the ATF and the president of one of its perennial targets.

What ensued was an ugly airing of the Mongols’ dirty laundry. In one corner was the group’s longtime attorney, Joseph Yanny, who could hardly conceal his contempt for a former client he now considers a double agent. In the other was Santillan, who noted bitterly that he’d been drummed out of the Mongols and unfairly labeled a rat without “due process.”

Founded in Montebello in the 1970s, the Mongols are what the ATF has dubbed an “outlaw motorcycle gang,” along with the Hells Angels, Pagans and Vagos, among others. Though their members insist they are little more than social clubs, authorities say they murder one another in bitter rivalries and deal drugs and guns.

A short, well-built man with tattoos that climbed above the neck of the collared shirt and blue suit he wore to court, Santillan, known as “Little Dave,” testified that he joined the Mongols in 1997. A year later, he was admitted to “Mother Chapter,” a governing body within the club.

After spending a year in Lompoc penitentiary for mail fraud, Santillan returned in 2000. Ten years later, he was tapped as president.

Yanny asked Santillan what his current status was within the club.

“I don’t have one,” Santillan said.

Wasn’t it true he was what the Mongols called “out bad”?

“So you say,” Santillan shot back. He preferred the term “in limbo.”

After his wife circulated what he called “the infamous video” and labeled him as an informant, Santillan was stripped of his title and excommunicated, he said angrily.

He said he has not mended relationships with his onetime biker brothers, about a dozen of whom sat stonily in the courtroom as Santillan testified. But he has reconciled with his wife; the two have set aside their divorce proceedings and are living together.

Must Reads: Could a notorious biker club’s survival hinge on a trademark? The feds are betting on it

When federal prosecutors finally managed to put mobster Al Capone behind bars, it wasn’t for murder or bootlegging, but tax evasion.

Yanny grilled Santillan about Ciccone, a self-described “street agent” who retired in December after a 32-year career with the ATF, much of it spent investigating the Mongols and other motorcycle clubs. Santillan said he met Ciccone around 2013, while in court for an earlier racketeering case brought against the Mongols.

Santillan said he spoke with Ciccone only a handful of times over the years, mostly when the agent was surveilling Mongol gatherings.

“It was small talk, and I always had someone around me,” he testified. “It was very brief. Minutes, if that.”

Ciccone, he said, was a “fair” lawman who “never put no bullshit case on the club.”

When Ciccone took the stand, he told Carter there was nothing secret about his relationship with Santillan, which had been limited to “public safety issues.” He said he had developed “an open line of communication” with Santillan; to prevent violence at public events, the men would meet in front of other Mongols as a “deterrent.”

“That shows the Mongols the ATF are here,” he testified. The agent recalled telling Santillan and his subordinates, “We’ll let you have your fun; just keep your people in check, so to speak.”

“I’d do the same thing if I was meeting with some Hells Angels,” he added.

As the racketeering trial approached in 2018, however, prosecutors told Ciccone he should stop speaking with Santillan, he said.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

“We figured he was going to be the face of this case, so they said, ‘Hey, try not to have any more conversation with him,’ ” Ciccone recalled. He denied, however, that prosecutors ever told him his interactions with Santillan up to that point were improper.

Much of the hearing hinged on Santillan’s drunken comment to his wife that “John” would no longer be able to “protect” him. The comments, Santillan said, stemmed from a day he went to an ATF building to pick up boxes of Mongols property that were being returned after the trial.

He and Ciccone were “shooting the breeze” when the agent said he was retiring in a year. He suggested that Santillan consider doing the same, because “whoever takes his place might not be as nice,” Santillan recalled.

The agent, Santillan said, reminded him that he hadn’t been arrested for any serious crimes during his time as the Mongols’ president.

Santillan claimed that he had stayed out of trouble because he “cleaned house,” putting an end to the drug dealing and shootouts that invited indictments. “I figured I didn’t get indicted in 13 years, I was ahead of the game,” he said.

“Almost like you had a guardian angel?” Yanny asked.

Santillan didn’t reply.

Ciccone and Santillan denied having a secret alliance, but Yanny was intent on proving that the Mongols’ onetime president had tried to undermine the club’s defense at trial.

He grilled Santillan about an email he’d sent in the lead-up to the trial, in which Santillan demanded that Yanny remove himself and Ciccone from the defense’s list of witnesses.

The instruction bothered Yanny. He replied to Santillan that it put him in “a near impossible position,” and without Ciccone’s testimony, “we have no chance of winning this case.” The agent, he noted, supervised all of the informants and undercover agents who had infiltrated the Mongols. Failing to call the agent to testify, he added, would fall “below my duty to act as a zealous advocate.”

Now, in light of the recording, Yanny tried to paint the request as part of Santillan’s larger plan to undermine the Mongols’ chances at trial.

Why, he demanded, had Santillan wanted to keep the agent off the stand? Was he afraid of Ciccone?

“The whole club is,” Santillan said.

Santillan pushed back, claiming that Yanny was consumed by a “personal issue” between himself and Ciccone and prone to “ranting and raving” about the agent. He reminded Carter that during the trial, the lawyer had accused Ciccone of stoking conflict between the Mongols and the Hells Angels, then sitting back when they erupted into violence. The allegation, Santillan said, was “a conspiracy theory by Joe Yanny.”

Santillan said he hadn’t wanted Ciccone to testify because the jury would have been put off by Yanny’s deeply personal line of attack.

“You told me you were going to badger him on the stand,” Santillan told Yanny, “cut his head off and s— down his throat.”

Yanny denied this.

Ciccone remained on the witness list, but Santillan said that shortly before the Mongols rested their case, he, Yanny and the Mongols’ other attorneys voted unanimously in the hallway outside of Carter’s courtroom against calling him. Even if he had wanted to dictate the club’s trial strategy, Santillan said, he didn’t have the power to do so.

Yanny called it “an outright lie” that it was decided by a vote — and not by Santillan himself. He pointed to a text message Santillan sent to another attorney during trial: “Joe doesn’t call the last shot I do,” he wrote.

Yanny questioned Santillan about an encounter with Ciccone at a Starbucks near the courthouse, which a juror witnessed and reported to the U.S. Marshals Service. “There was nothing inappropriate,” Santillan said. “It was a chance encounter.”

Yanny also showed the court a photograph of Santillan sharing a couple of Bud Lights with Christopher Cervantes, a retired Montebello police lieutenant who partnered with Ciccone on investigations of the Mongols. Santillan explained that he was bowling last year with his grandchildren after being exiled from the Mongols when he ran into Cervantes at the bowling alley’s bar.

Asked what they discussed, Santillan again said they were “just shooting the breeze.”

“You didn’t see a problem meeting with the enemy?” Yanny asked.

“I’m a civilian now,” Santillan said.

After two days of testimony from Santillan, his wife and Ciccone, Carter continued the hearing without ruling on the Mongols’ request for a new trial. Ciccone will resume testifying July 22, and Yanny has indicated that he intends to call witnesses who will dispute some of Santillan’s account.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.