A documentary about a wrongfully incarcerated Korean immigrant unearths an essential, buried history

- Share via

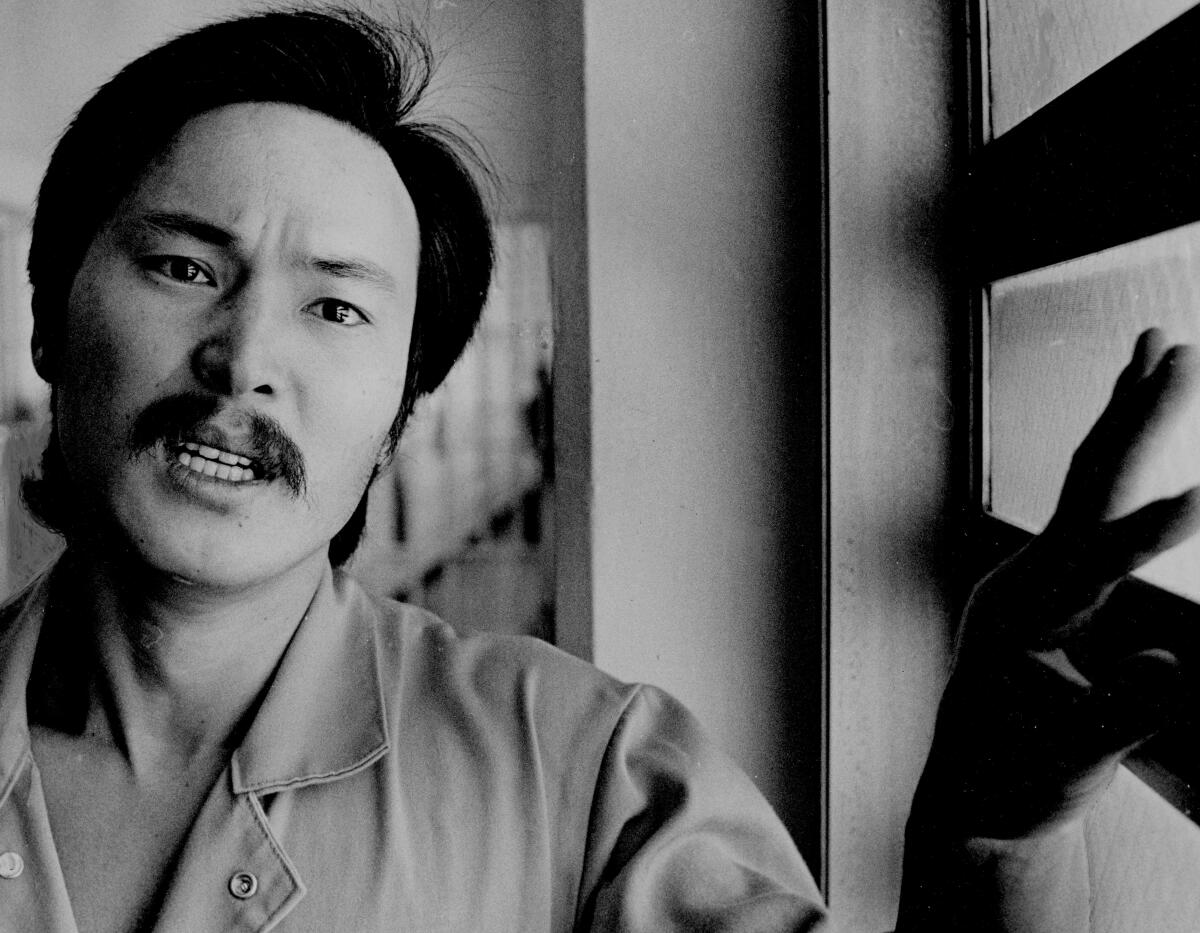

K.W. Lee, a pioneering Asian American journalist, helped free Korean immigrant Chol Soo Lee with a series of investigative news articles in 1978.

But he had never expected to outlive Chol Soo, who had become like a son to him. At his funeral in 2014, K.W. Lee delivered a raw, aching eulogy that was also an angry call to action, said Julie Ha, a journalist who was in the crowd that day and one of the creators of a new documentary, “Free Chol Soo Lee.”

Update:

6:44 p.m. Aug. 26, 2022This article has been edited to correct the spelling of Eugene Yi’s name as well as to clarify details about the creation of the documentary “Free Chol Soo Lee” and reactions to it.

The aging journalist ignored the podium and faced the crowd of activists, public servants and community organizers gathered at a San Bruno Buddhist temple to remember Chol Soo, dead at the age of 62. He gripped a Buddhist monk’s walking stick in one hand, and punched the air as he spoke in a voice cracked and hoarse.

“He wanted to know why Chol Soo’s story was still underground after all these years,” Ha said. “Why this history of a landmark Pan-Asian American social justice movement had been all but forgotten.”

There was a heaviness in the room that went beyond grief, Ha said. That day planted the seed of “Free Chol Soo Lee,” a documentary that would take over the next seven years of her life.

With co-director Eugene Yi, the documentary tells the story of Chol Soo, his immigration at the age of 12, his early years in San Francisco, his wrongful imprisonment for the 1973 murder of a Chinatown gang member and his later struggles with addiction and mental health.

It is a masterful reporting of a story that, despite receiving national attention at the time, was largely forgotten.

At the time, coverage of Chol Soo’s case in this newspaper and elsewhere tended to highlight J. Tony Serra, an eccentric former civil rights attorney who took on his case. A Los Angeles Times story called Serra a “true believer,” a phrase that later became the title of a 1989 film dramatizing the events of Chol Soo’s exoneration.

I saw “True Believer” for the first time last week. I thought it was a sincere, idealistic film full of charismatic rants about racism and a flawed criminal justice system.

A charitable interpretation of the film might argue that Serra is an interesting character, and casting James Woods and Robert Downey Jr. as the true heroes and Asian Americans as silent observers may have helped get the film a wider release. It would note that even though the film came out after Chol Soo was freed in 1983, the film’s existence likely brought positive attention to the case that was helpful to Chol Soo’s cause.

But too often this is how Hollywood obscures history, intentionally or not. A white-dominated industry took an Asian American story, edited out the Asian people, and made two white guys the heroes, earning everyone millions of dollars in the process.

Ranko Yamada, one of Chol Soo’s earliest supporters and an organizer of his defense committee, called it “so sanitized.”

“That’s what the public would like to hear. That one is pretty much a clean story,” Yamada said. “You don’t walk away feeling bad about anything or knowing that a whole people go through this kind of treatment. That wasn’t our movie.”

The film paints an easy-to-condemn caricature of white racism. The bad guys are clearly identified with giant red Nazi flags, members of the murderous, antisemitic Aryan Brotherhood. And that choice, intentionally or not, steals focus from the real, widespread and systemic racism that defined Chol Soo’s case.

A central flaw in Chol Soo’s prosecution was that the San Francisco Police Department lacked the connections in Chinatown needed to interview most witnesses at the scene — a crowded Chinatown intersection.

A white detective with no Chinatown contacts identified three white men as key witnesses. And though it is later shown that these men were unable to tell the difference between different types of Asian people, their testimony puts Chol Soo in prison with a life sentence.

The Hollywood version sidesteps these difficult racial discussions by changing the race of the killer to a non-Asian person. Chol Soo is portrayed as a man grateful to his attorneys but uneasy with the support drummed up by his community. K.W. Lee, whose dogged coverage of the case brought national attention to it, was excluded entirely.

I think the film is a textbook example of the ways Hollywood obscures history. There are no violent neo-Nazis with obvious, visible swastika tattoos, torching historical archives as they shout racial slurs. Systemic racism more often looks like regular people making decisions that seem convenient, practical and profitable.

So “Free Chol Soo Lee” is more than a documentary. It is an act of historical restoration. It skips easier narratives in favor of the hard work of telling a true, complicated story. And it’s through that unglamorous, unselfish work that history is restored.

A few months ago, Ha heard from K.W. Lee, who had been her mentor in journalism since she was 18 years old.

“Now I feel that Chol Soo Lee is finally truly free,” he said in an email.

All Asian Americans should learn Chol Soo’s story. It makes me angry that we forgot it, because it is full of the things this community is still searching for today.

Chol Soo Lee was not an ordinary civil rights hero. He was a convict who killed an inmate, a member of the Aryan Brotherhood. He was a drug addict who continued to struggle with drugs after his exoneration. He was a man created by the system and destroyed by it.

But he never forgot his humanity or the injustice of his situation. In his prison memoir, “Freedom Without Justice,” he questions his belief in the “purity and greatness of justice in America.”

“How do we mistakenly believe something even when the contrary reality is written right in front of our eyes in big letters?” he writes of his experience in the criminal justice system. “No matter how painfully that reality is hurting us, we have our reasons for refusing to see it clearly.”

And he was embraced by an Asian American community that saw past his missteps. He convinced conservative, church-going Korean American immigrants and pot-smoking activists alike to show solidarity for the incarcerated. Supporters wrote him letters and visited him in prison when even Chol Soo’s own mother was convinced of his guilt. Some students — including a young Jeff Adachi, the late public defender of San Francisco — recorded a protest song about his plight and attempted to get it on the radio.

Yamada even convinced her parents to put their home up as collateral for Chol Soo’s bail. They threw him a party when he got out of prison.

That radical care and love between Chol Soo and his community is what Yamada hopes people remember more than anything else.

“I just hope people learn to not judge so quickly and to take a closer look. To not be so suspicious and paranoid and closed. To see that great things can be accomplished when you extend yourself, a little bit,” Yamada said.

“Asian American” was just coming into use as a term around the time of Chol Soo’s case. But Asian Americans around the country didn’t need a perfectly defined term to start caring about Chol Soo.

And that care created its own legacy. Organizers of Chol Soo’s defense would later go on to create service centers and legal aid funds that today help immigrants in similar situations.

Adachi’s early involvement with the case inspired his legal career and later work as a public defender. And it was the same for Mike Suzuki, who currently works as a division chief at the Los Angeles County public defender’s office.

“I think about Chol Soo every day,” Suzuki said. “I just miss him. I would not have anything I have gotten in the last 36 years if it were not for Chol Soo.”

Why do we remember Vincent Chin, the Chinese American killed by two autoworkers in Detroit, but not Chol Soo Lee? Is it because Vincent died and Chol Soo lived, and one story was easier to tell than the other?

“Sometimes we just have to take a hard look in the mirror,” Ha said. “Sometimes we buy into our own model minority myth. Why did we choose not to talk about this movement, arguably the first of its kind?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.