Judge blocks county watchdog investigation into sheriff deputy gangs, tattoos

- Share via

In a 42-page ruling that is sure to be contentious, a civil court judge effectively blocked the county watchdog from thoroughly investigating deputy gangs that operate within the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

The lengthy decision, dated Monday but released a day later, is the latest development in an ongoing lawsuit over whether suspected members of deputy gangs can be forced to answer questions and show their tattoos to county oversight investigators.

The Assn. for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs — which filed the suit in May — said requiring its members to reveal ink or submit to interviews would violate the 4th Amendment’s ban on unreasonable searches and the 5th Amendment’s protections against self-incrimination, as well as state labor law.

Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge James Chalfant partially agreed — for now. But it was the arguments relating to labor law that he found most compelling, so this week’s preliminary injunction will only halt the Office of Inspector General’s investigation until the labor issues are resolved.

Given how long the county’s efforts to investigate deputy gangs have already taken, the judge said there was no urgency in moving forward with the probe immediately.

“The county will face little to no harm from a preliminary injunctive relief because the tattoos are permanent and will be available for inspection after a trial on the merits,” Chalfant added.

Still, civil rights experts worry the decision could have broader implications for efforts to hold law enforcement accountable, effectively undermining a 2021 state law aimed at eradicating deputy gangs.

“It could have a chilling effect,” said Andrés Kwon, senior policy counsel with the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. “The law mandates all law enforcement agencies to clearly prohibit deputy gangs and to cooperate with investigations into deputy gangs, essentially. It’s a clear mandate, and ALADS is trying to block this law from being implemented.”

In Los Angeles, the ruling presents a significant roadblock to the Office of Inspector General’s investigation.

“I’m disappointed that deputy gangs will remain for now, and I expect the county will appeal,” said Inspector General Max Huntsman.

“It’s been a year and a half since California outlawed the gangs without meaningful investigation by law enforcement,” he added. “My office will continue to work toward the day when the Sheriff’s Department is no longer above the law.”

The Sheriff’s Department deferred comment to county counsel, and the county deferred comment to the inspector general. Richard Pippin, ALADS president, said the union was “glad to see the court has issued an injunction,” but declined to comment further before reviewing the document in full.

To the families of those killed by sheriff’s deputies, the ruling came as a disappointment.

The ruling is honestly not surprising,” said Stephanie Luna, whose nephew was killed by deputies in 2018. “But it’s concerning because it shows no matter what the deputies do, the system is always going to work to protect them.

For nearly half a century, the Sheriff’s Department has been plagued by rogue groups of deputies allegedly running roughshod over certain stations and promoting a culture of violence. A Loyola Marymount University report released in 2021 identified 18 such groups that have existed over the last five decades, commonly known by names such as the Executioners, the Banditos, the Regulators and the Little Devils.

A new report by the Civilian Oversight Commission condemned the “cancer” of violent deputy gangs in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and urged a ban on the secretive groups.

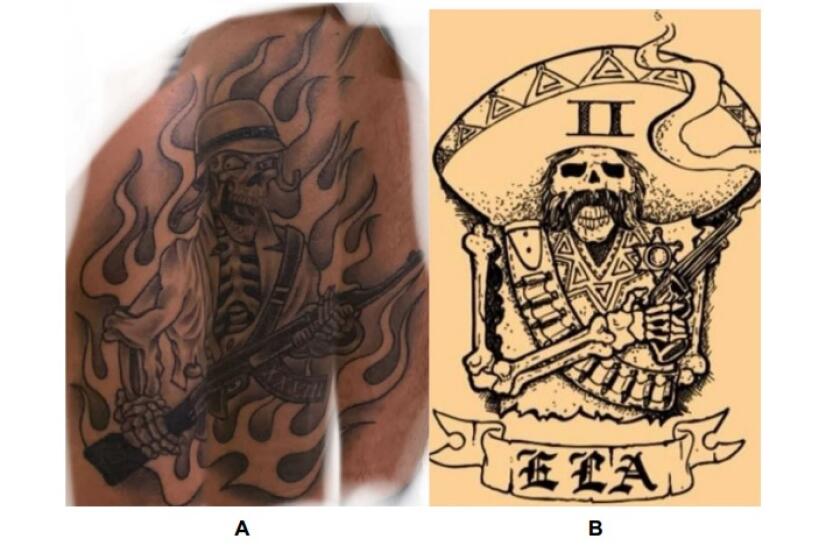

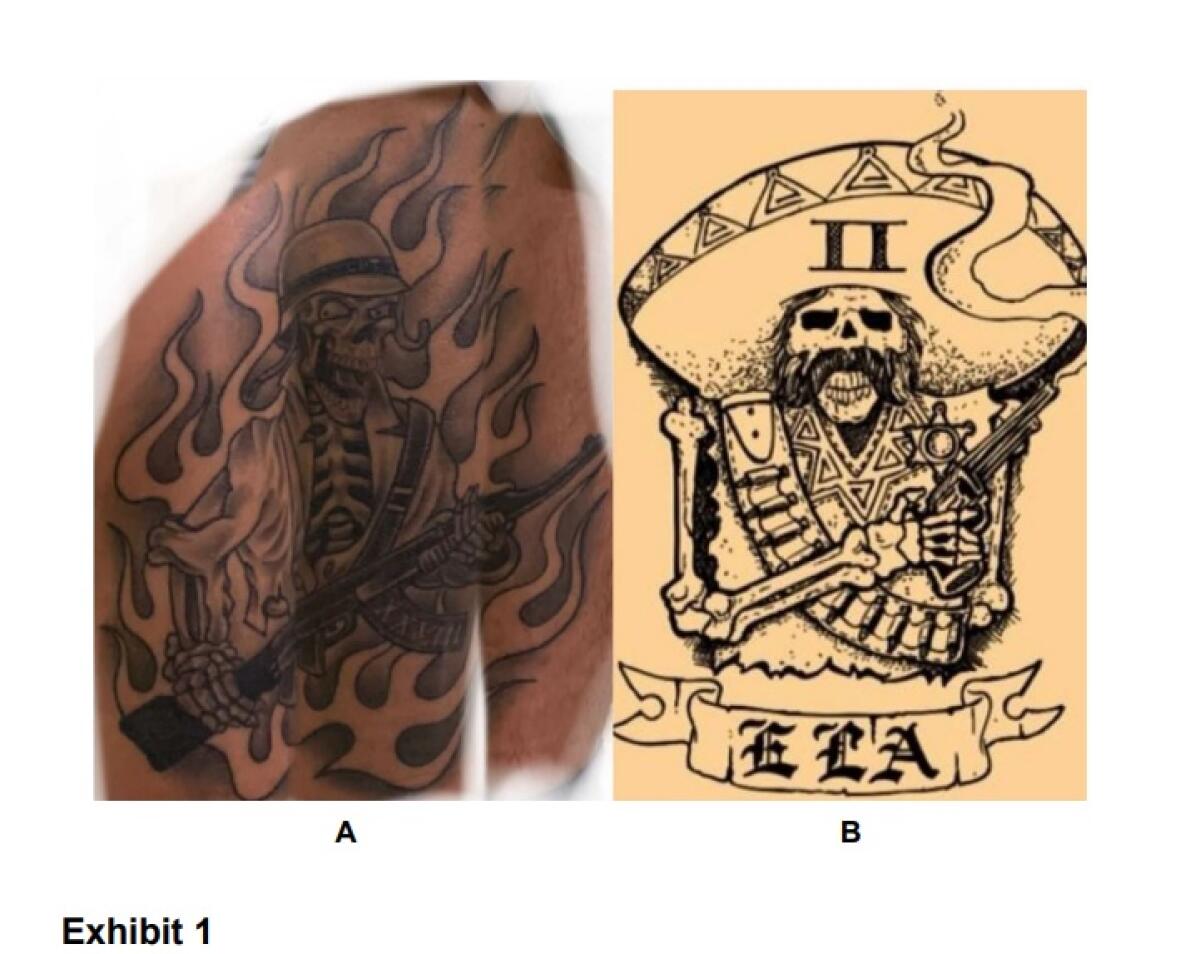

Members of the groups are alleged to have matching, sequentially numbered tattoos, such as the flaming skeleton wearing a Nazi-style helmet associated with the Compton station group or the sombrero-wearing skeleton with a bandoleer and pistol linked to the East Los Angeles station group.

Before he was ousted from office last year, then-Sheriff Alex Villanueva repeatedly denied the existence of such groups and blocked the inspector general’s investigative efforts, even going so far as to ban Huntsman from the department’s facilities and databases. After Sheriff Robert Luna took over as the county’s top cop in December, he restored Huntsman’s access and vowed to “eradicate all deputy gangs” from the department.

In May, the Office of Inspector General sent letters to 35 deputies suspected of being members of the groups commonly known as the Executioners at Compton station, or the Banditos at the East L.A. station.

Facing long-standing allegations of “appalling” conditions inside the county’s jails and violent deputy “gangs” operating on its streets, Sheriff Robert Luna announced a new office designed to combat those problems.

The letters ordered deputies to come in and show their tattoos, give up the names of any other deputies sporting similar ink and submit to questions about whether they’d ever been invited to join a group related to their tattoos. The ultimate goal was to develop a list of every alleged deputy gang members in the department, Huntsman said at the time.

Initially it wasn’t clear whether there would be any consequence for refusing to cooperate. Then, Luna sent a department-wide email, ordering his staff to comply with the inspector general’s request or face the possibility of discipline or termination.

In response, ALADS filed a labor complaint as well as the state court lawsuit that led to this week’s preliminary injunction.

At first, Chalfant issued a temporary restraining order in late May, blocking the county from forcing deputies to come answer questions or show their tattoos. Then in late June, the judge heard arguments from the county and the union about whether the terms of the restraining order should stay in place as an injunction or whether the inspector general’s investigation should be allowed to move ahead.

Days after the county’s inspector general demanded that dozens of deputies reveal their alleged gang tattoos, employee unions filed a both labor complaint and a lawsuit.

In court, the judge repeatedly expressed concern about the allegations swirling around deputy gangs, some of which he said sounded like “criminal behavior.” He also questioned whether 5th Amendment protections against self-incrimination would really apply, since it is not illegal to be in a law enforcement gang — even though it can be grounds for termination.

The union’s attorneys argued that forcing deputies to show their tattoos even by raising up a single pant leg would be an “unreasonable search” in violation of the 4th Amendment. Lawyers for the county explained that they’d narrowed the scope of the proposed investigation to focus on tattoos in visible places such as the face, neck and below the knee. They also questioned why showing a leg would be unconstitutionally invasive “unless you never wear shorts.”

The union’s lawyers also said that even though the new state law requires policing agencies to cooperate with inspector general investigations, the county needs to bargain over the parameters and logistics of any such investigation before ordering deputies to comply.

Lawyers for the county said there was a “fundamental disagreement as to whether there is a bargaining obligation” at this point in the process, and the judge questioned whether the law actually requires deputies to cooperate with investigations or whether it only requires the sheriff to cooperate as the head of the agency.

After last month’s hearing, the judge spent nearly two weeks weighing the harms of blocking the investigation versus the harms of possibly violating labor obligations.

“The harms to the public from gang activities are substantial and weigh heavily in balancing the interests affected by a preliminary injunction,” he wrote. “LASD deputy gangs also cause harm to the County by eroding public trust in law enforcement, undermine the chain of command, promote racism, sexism, violence, intimidate other deputies, and are a significant liability to the county.”

But Chalfant said the county is statutorily obligated to bargain with the deputies’ union before putting in place significant changes — such as requiring deputies to show their tattoos. And since the tattoos are permanent and county investigators have settled on a “cumbersome process” that will take some time, Chalfant came down in favor of the deputies and their labor concerns.

“While the OIG surely is impatient at the delay, there is no compelling need for immediate investigation,” Chalfant wrote.

The parties are due back in court in September.

Times reporter James Queally contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.