What’s in illegal drugs? A UCLA team takes testing to the streets to find out

- Share via

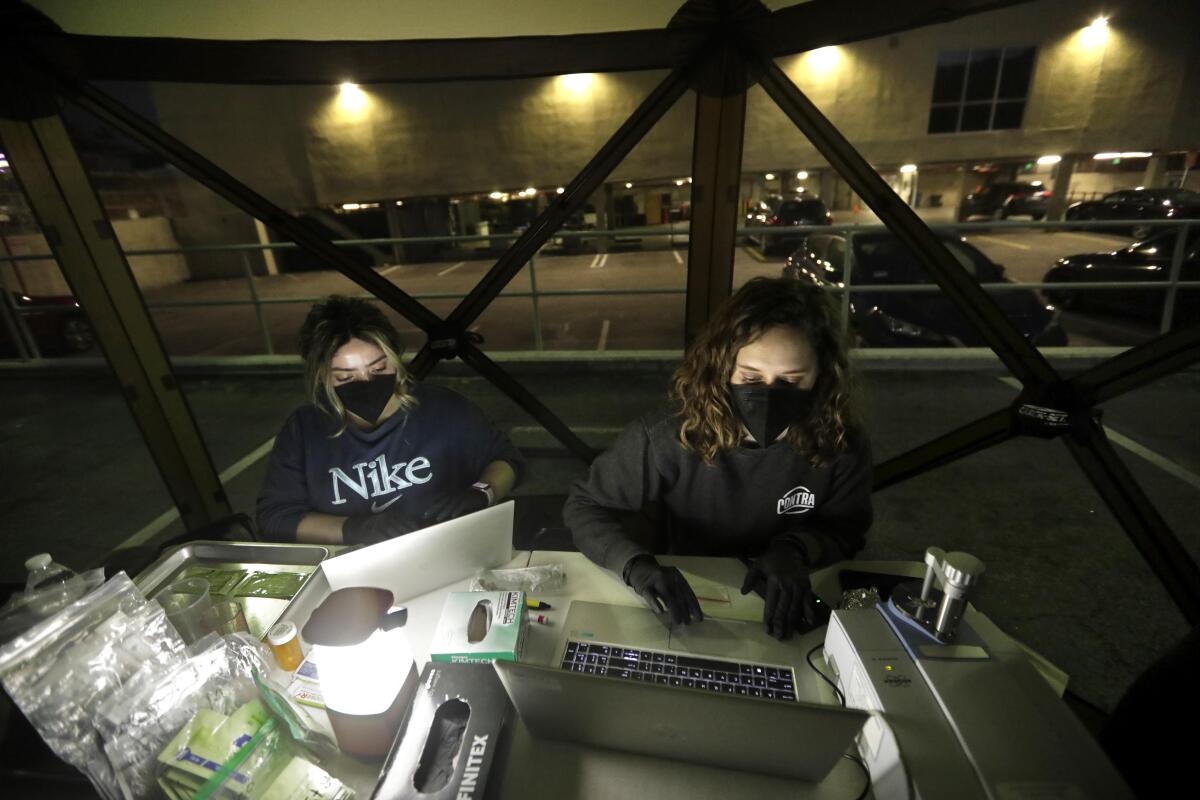

Under a tent pitched in a darkened parking lot in Los Angeles, a 21-year-old man handed pills to Ruby Romero.

“Can you test all of them?” he asked. “I’d rather be safe than sorry.”

Romero, a UCLA project director, started to ask questions for an ongoing study as the young man shifted in the evening cold from foot to foot in his sandals. He told Romero that the vividly orange pills, which were shaped like rounded triangles, had been sold to him as ecstasy.

But before he headed to a rave in San Bernardino, the man wanted to make sure that he wasn’t accidentally giving something else to his brother or his brother’s girlfriend. His biggest worry was fentanyl, the powerful synthetic opioid that has driven up overdose deaths in Los Angeles County.

“I don’t want that on me,” he said.

The man had driven from Downey to Los Angeles to find test strips to detect fentanyl that were being handed out by a syringe program in the parking lot. But the UCLA team stationed nearby was offering him a chance to unmask other hidden threats by analyzing a tiny sample of a drug to reveal its components.

To do so, the team is bringing a sophisticated machine traditionally used in laboratories to the streets, road-testing a public health strategy that has gained more attention as deadly overdoses have surged. The UCLA team sets up at sites where Angelenos ordinarily access clean syringes and other health supplies. Their machine, which uses a technique called Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, is roughly the size of a computer scanner.

“The real promise is using this technology to understand something that’s really been mysterious for a long time — what the heck is in the illicit drug supply?” said Chelsea Shover, assistant professor in residence at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine and lead investigator for the pilot study.

In Los Angeles County, a growing number of deadly overdoses involve a mixture of drugs. In 2021, roughly 64% of overdose deaths among homeless people in the county involved more than one drug — up from 45% three years earlier, according to a county analysis.

Fentanyl has ramped up overdose deaths since it pervaded the drug supply in L.A., but health officials have also warned about the emergence of other threats such as xylazine, an animal tranquilizer that can cause gruesome wounds and that started showing up years ago in illegal drugs on the East Coast. Shover and her team detected xylazine in drug samples earlier this year, confirming that the drug also known as “tranq” had made its way to L.A. County.

The UCLA study is also assessing whether more-refined forms of drug checking are helpful for consumers on the street. The kind of machine the team is using can cost between $35,000 and $50,000 depending on its software, Shover said. It needs a skilled staffer to run it and interpret the results.

Shover said that programs that consider investing that kind of money want to know, “Are people going to use it? Is this going to give us new information, beyond what we can get from just asking people?”

So far, “we’ve been able to show this is something that clients are interested in,” Shover said.

Romero gloved up and shaved a bit off one of the orange pills with a razor blade, then crushed it inside a plastic bag, which she handed off to UCLA project manager Caitlin Molina, stationed behind the machine. Molina, also in gloves, spooned out

a tiny bit of the sunset-colored powder onto the center of the spectrometer.

“It’ll just take a second for it to shine the light through,” she assured the young man.

What showed up on her screen was a jagged line that Molina described as a kind

of fingerprint, the result of wavelengths produced by chemicals within the drug sample. A computer program offered up suggestions for the closest matches, which Molina could then compare to the peaks and valleys of that line.

If a particular drug such as methamphetamine looks like a match, Molina can then analyze what the ridged line would look like if the distinctive pattern from that drug were eliminated. If telltale peaks indicating another substance continue to show up after doing so, she can check for another match.

“We keep matching until there are no more good matches,” Shover said.

The result is a short list of the chief components in the drug sample. Shover cautioned that the machine would not detect substances that are present in small amounts — 5% or less of the sample — so the team also checks samples with test strips for fentanyl and benzodiazepines, both of which can be dangerous even at smaller concentrations. When test strips for xylazine became available this year, the UCLA team started using those as well.

The orange pills, for instance, plainly contained MDMA, also known as ecstasy. The squiggle on the screen also seemed to hint at an additional element, something Molina couldn’t easily match to common fillers like sugar. Romero checked a bit of the same powder with test strips, finding it negative for fentanyl and benzodiazepines.

It was unclear whether anything else might have been in the sample in small concentrations, but the results nonetheless reassured the 21-year-old as he prepared to go to the rave. His biggest worry was fentanyl.

“It’s not something you can prepare yourself for,” he said.

Testing each sample with the machine and test strips typically takes 10 minutes or less, according to the UCLA team. The researchers also send swabs of residue to an outside lab for additional testing. That involves an even more precise machine, and it can take roughly a week to return results.

Molina said the pilot study has been welcomed enthusiastically by people stopping by syringe programs, some from as far away as Palmdale or Orange County.

Such on-the-street analysis could help untangle one of the questions that

has nagged researchers and officials in L.A. County: Whether the growing number of overdoses involving more than one drug is because people are mistakenly consuming something or because they’re intentionally mingling drugs.

As of mid-July, the UCLA team had analyzed more than 300 samples at community sites. The researchers are still carrying out their work, but so far have found that the vast majority of samples that users expected to be meth alone have turned out to be just that. None of the samples that were believed to be meth alone contained fentanyl or other opioids, according to testing done as of mid-July.

If that pattern persists as testing continues, it could indicate that many L.A. County residents are purposely using meth and fentanyl together, rather than being blindsided by meth contaminated with the synthetic opioid. Public health officials found that in 2021, more than 40% of overdose deaths among unhoused people in L.A. County involved a combination of drugs that included both meth and fentanyl, according to a county report.

Drug contamination is “a huge problem,” but there is probably more intentional mingling of drugs than is reported because “certain substances are more stigmatized than others,” said Meghan Hynes, a harm reduction consultant in Los Angeles. In some cases, “folks are intentionally using both, but they don’t want to admit it.”

Another possibility is that mixing is not being done intentionally as drugs are made, but is happening accidentally right before they are used, possibly through shared equipment.

There is also the question of how checking drugs might change the way people consume them in L.A. Even if testing detects something unexpected or unwanted in a drug sample, some people may go ahead and use it because they don’t have other drugs at hand. But knowing what is there could spur people to change the way they take the drugs — by smoking rather than injecting them, for instance, or by ensuring someone else is nearby to watch over them.

“Ultimately, I want drug checking to be available to people so they can can make informed decisions,” said Amy Judd Lieberman, a senior attorney at the Harm Reduction Legal Project, which is part of the Minnesota-based Network for Public Health Law.

That was what kept the Downey man waiting for the results that brisk evening under the tent as the UCLA team checked each of his orange pills.

“If you’re going to party,” he said, “at least party safe.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.