Mr. Ayers ends up in the hospital, a reminder that problems with nursing home oversight remain

- Share via

With a new violin in hand, I walked into a nursing home for seniors in southeastern L.A. County, eager to see the look on my buddy Nathaniel’s face.

A once-promising career as a classical musician was hijacked half a century ago with a diagnosis of mental illness. But a continuing love of music keeps him alive, and I had promised to replace his broken violin and cello.

When I arrived, a nurse informed me that Mr. Ayers, as I call him, wasn’t there. He’d been hospitalized after what appeared to have been a colossal screw-up. A month earlier, when he was transferred from a nearby facility to the nursing home, there’d been a miscommunication about his condition and treatment plan. As a result, his glucose levels were dangerously high.

California is about to be hit by an aging population wave, and Steve Lopez is riding it. His column focuses on the blessings and burdens of advancing age — and how some folks are challenging the stigma associated with older adults.

I drove to the hospital, worried and angry. Mr. Ayers has lived a hard life, spending the bulk of his 72 years in institutions and on the streets. When I met him in 2005, the Juilliard-trained musician was living on Skid Row in Los Angeles, playing a violin that was missing two strings. We’ve been close ever since, and I’ve tried my best to monitor his care as he’s bounced from one facility to another.

By chance, the same day I learned of Mr. Ayers’ hospitalization, my column on nursing homes was published. President Biden’s call to beef up staffing was a small step in the right direction, I wrote, but overdue inspections and delays in complaint investigations needed attention, as well. I quoted Tony Chicotel, of California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, who asked: “Has California nursing home oversight ever been worse?”

I found Mr. Ayers asleep in his hospital bed, sharing a room with two other patients who were also snoozing. I didn’t want to wake him, or them, so I left a note asking him to call me. A nurse advised I hold onto the violin so it wouldn’t get stolen.

Mr. Ayers was treated — crisis averted, thankfully — and later returned to the nursing home. But when I went back to give him the violin, the medical staff warned me to keep my distance. Mr. Ayers was congested and his eyes were glassy, and they were about to test him for COVID-19. I handed him the violin, which brought a smile to his face, and then I flagged down the nursing director.

She told me she would check the records and call me later. When she did, she confirmed that there had been some kind of communication breakdown regarding his condition and meds. She also said that after I dropped off the violin, Mr. Ayers was shipped back, yet again, to the hospital. He had tested positive for COVID-19.

While this was happening, L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer contacted me to push back a bit on my column about nursing home oversight. In L.A. County, she said, a host of improvements have been made since numerous deficiencies were cited by both the auditor-controller and the office of the inspector general. Many of the additional recommended reforms were beyond county purview, she said, and would need to be addressed by the state.

Ferrer put me in touch with two members of her team — Dr. Nichole Quick and Dr. Zachary Rubin. They said great strides had been made in controlling the spread of infectious diseases at nursing homes, and the complaint investigation backlog had been virtually eliminated.

But problems remain. Some facilities are antiquated, Dr. Rubin said, staffing is an issue in some places, and turnover rates are high. There are good owner-operators and bad operators, Quick said.

As I noted previously, lax state licensing controls have allowed owners with shoddy records to stay in business. And a $30-million court settlement earlier this year in a negligence and wrongful-death case against a nursing home highlighted an alarming reality — ownership webs involving private equity partners can put a squeeze on nursing home staffing and lower the quality of care in the interest of maximizing profits.

I do want to say that in my hundreds of visits with Mr. Ayers at multiple facilities over the years, I’ve been impressed by countless hardworking employees dedicated to the care of patients whose physical and mental challenges can make the job extremely difficult. That many of these employees — primarily women of color — take home puny paychecks, while investors line their pockets, is unconscionable.

It’s no surprise that workers at nursing facilities in Los Angeles, Montrose, Norwalk and Claremont have voted to authorize a strike. In a statement, Service Employees Union Local 2015 said members are “demanding an end to skyrocketing staff turnover” and insisting on safer staffing levels “to ensure that all residents receive the high quality care they deserve.”

I saw the risks play out when I visited Mr. Ayers several months ago on a Saturday and found him in distress, yelling out in vain for assistance. It took me close to an hour to find his nurse, and while I searched, housekeeping employees told me staffing is often low on weekends.

After the treatment plan confusion earlier this month, I filed a formal complaint with the county Department of Public Health and shared everything I knew with investigators who visited both facilities. (I’m withholding the names of those places as the investigation proceeds.)

Quick could not discuss an active investigation but told me a discharging facility “definitely has a requirement to make sure” that medical records are forwarded in a transfer. Quick said if that didn’t happen in this case, and there was no “medication reconciliation” on the receiving end, it wouldn’t be the first time.

“There’s a ways to go on this,” she said of the need to make hand-offs more seamless.

Unfortunately, many patients don’t get regular visits from family or friends and have no advocates. Quick said the work of the county’s Long Term Care Ombudsman program is critical because it collaborates with the county, conducts investigations and makes unannounced visits to check on care and conditions.

But Molly Davies, CEO of Wise & Healthy Aging, which runs the ombudsman program, told me she has funding for only 30 staffers and 17 volunteers.

“With over 1,800 skilled nursing, assisted living and board-and-care facilities to cover, this is not enough,” said Davies, who is advocating for a direct and adequate source of funding for her program. As it is, she cobbles together money from various sources.

Some of these issues are complicated by fragmented authority at federal, state and local levels, but ageism plays a role. We simply aren’t caring enough to smooth the way for our elders and let them age with dignity. How hard can it be to shore up the ombudsman program and put more eyes and ears in facilities that are, to many patients, not just clinics, but homes?

Let me end, though, on a more upbeat note.

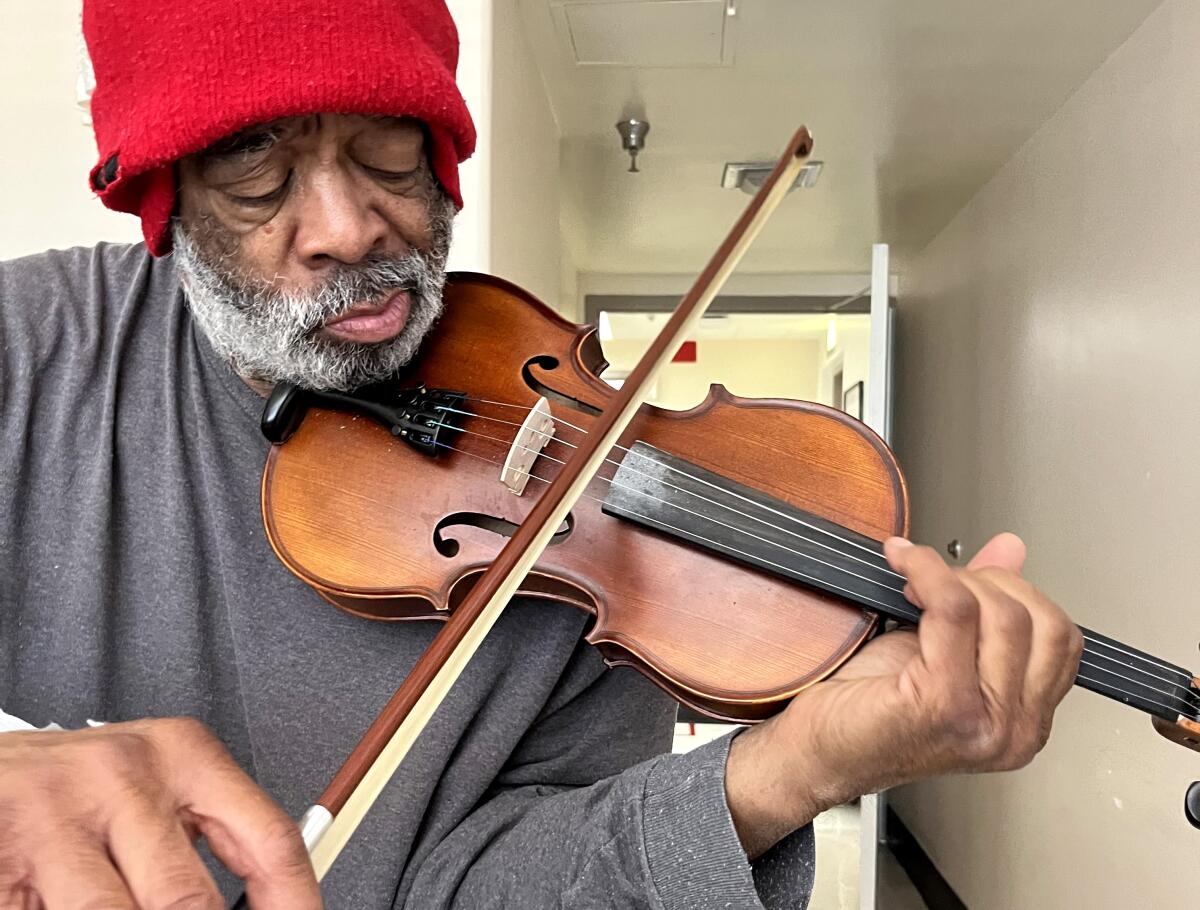

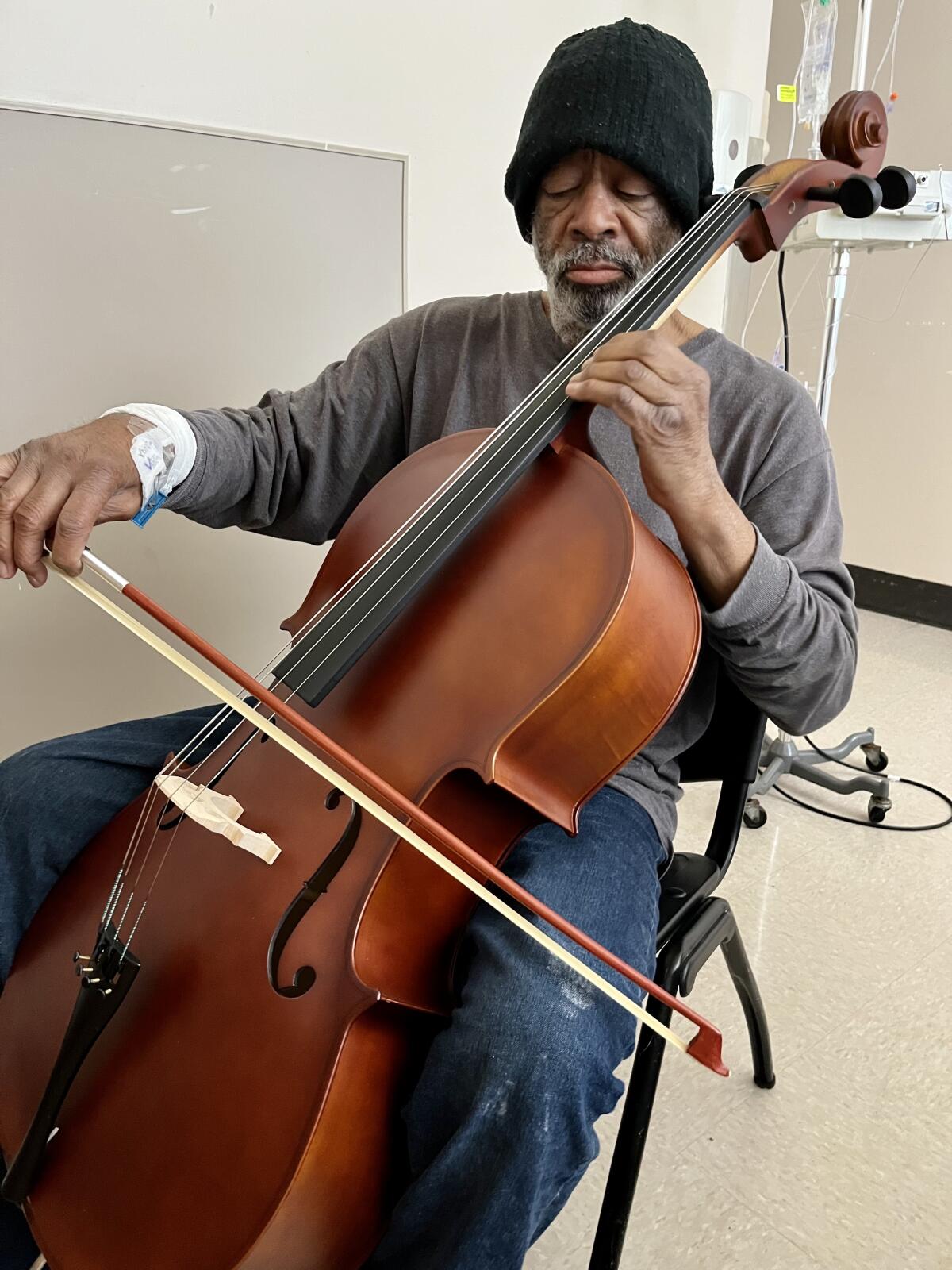

On Tuesday, Mr. Ayers called from the hospital, played his violin over the phone, and asked when I’d come by. He sounded well, and an administrator told me he was no longer positive for COVID. The next day, I took him a cello, and he treated me to a symphony.

First he played a portable keyboard he had lugged with him to the hospital, then the cello and finally the violin, turning a drab hospital room into a concert hall.

A couple of nurses came by and listened from the doorway. A doctor paused and smiled. The music traveled out of the room, down the hall and past the rooms of other patients, medicine for the soul.

steve.lopez@latimes.com

To file a complaint against a healthcare facility in California, visit the Department of Public Health website. You can also go to California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform at CANHR.org or call (800) 474-1116. In L.A. County, try the Wise & Healthy Aging Ombudsman page at wiseombudsman.org, or call (800) 334-9473 during working hours or (800) 231-4024 after hours.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.