Behind the story: Discovering the brotherhood of the Navy’s bomb squad

- Share via

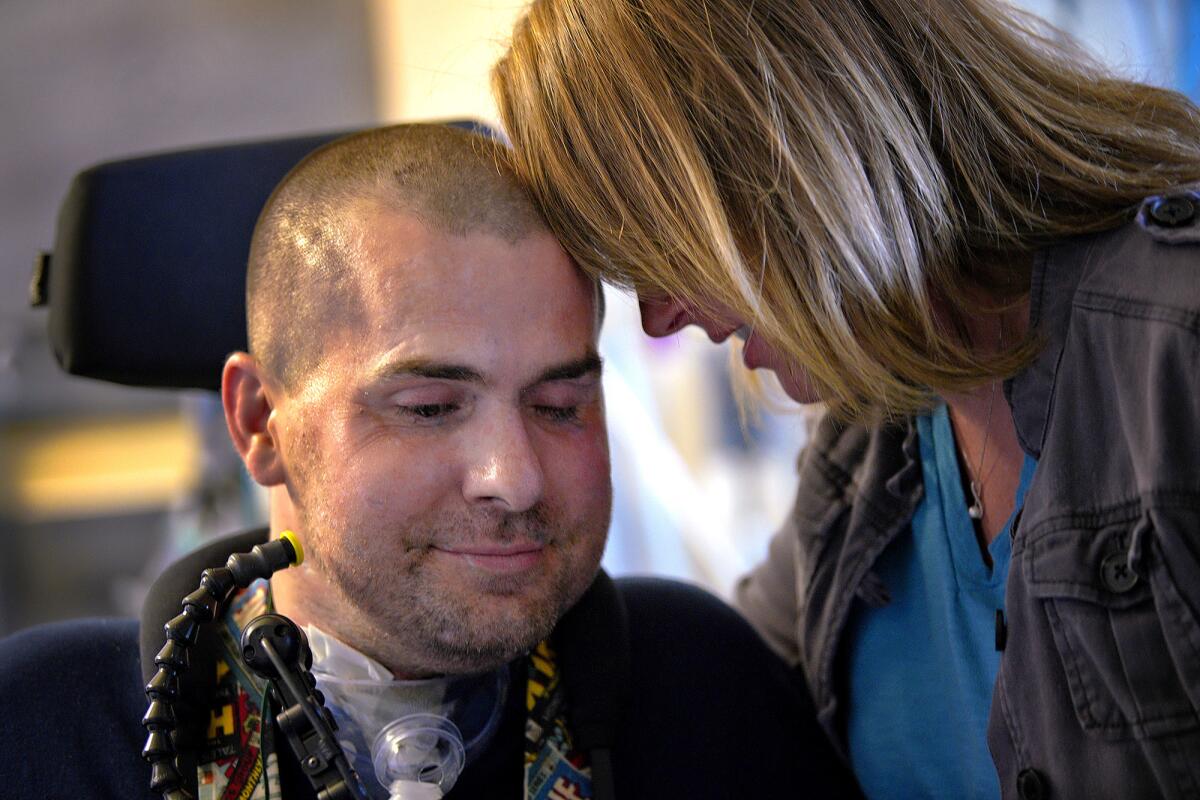

Reporting from SAN DIEGO — When I first visited Kenton Stacy at the Veterans Affairs hospital in La Jolla, I knew his wife, Lindsey, would be there. I’d been told to expect his mother, too, out from Ohio.

Geoff Shepelew surprised me.

He’s a Navy bomb technician, and as I quickly learned, part of an unbroken chain of support that started right after Kenton was injured by a bomb in Syria 18 months ago.

The Navy’s Explosive Ordnance Disposal team is a tight-knit group of about 1,800 enlisted sailors and 550 officers. Theirs is a bond forged by the work they do, underlined by a kind of gallows humor that shows up occasionally on T-shirts — “initial success or total failure” — and bumper stickers.

Since 9/11, about 150 bomb technicians in all branches of the service have been killed and 250 others injured, according to the EOD Warrior Foundation, a Florida nonprofit group.

“When there’s an injury, we all feel it,” Mark Brittain told me. He’s a Navy master chief who oversees bomb units on the West Coast. “What happened to Kenton could happen to any of us.”

So after the explosion, commanders assigned someone to be there with him in his hospital room. First in Texas, then in California. Every day. “We wanted him to know that he won’t be forgotten,” Brittain said.

The assignment was rotated, one week at a time. Except it wasn’t really an assignment. People volunteered, and not just the EOD techs. Special forces team members who had been on deployments with Kenton showed up, too. So did other Navy personnel. They hung out in his room for hours at a time, ran errands for the family, played with the kids.

Some flew in from the East Coast, and some came from San Diego. Some had worked with Kenton and knew his family. Some had never met him.

Shepelew, assigned to an EOD mobile unit based in Imperial Beach, walked into Kenton’s room at the VA in La Jolla in early March, carrying an electric massager. Kenton had been having trouble with neck pain the day before, and Shepelew thought the massager might help. He went out and bought one.

“There’s a camaraderie in this group that’s hard to articulate,” Shepelew said. “We’d do anything for each other. I know if something happened to me, they would be there for me, too.”

The Stacys welcomed the company. “It shows good support,” Kenton whispered. His wife: “What it tells me is they’ll always be there for him.”

A bomb blast, a phone call, and a Navy family forever changed »

The caring came through in other ways, too. An EOD parachute-rigger who had worked with Kenton and admired his strength and resilience got a tattoo in his honor. Squad members in Virginia pitched in to repair a house the Stacys owned in Chesapeake, Md., after a tenant trashed it. They helped make other fixes so it could be sold, and the real estate agent handling the sale donated her commission.

The EOD Warrior Foundation provided grants so that the Stacy grandmothers could fly out from Ohio and help take care of the couple’s four children. It held a fundraising run in San Diego last November and has another one scheduled this year.

“We’re a family,” said Nicole Motsek, the group’s executive director, “and families take care of each other.”

Sounds simple. Often isn’t.

Wilkens writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.