Who will inherit Greg Tate’s mantle of Black cultural critic-in-chief? I have a candidate

- Share via

The recent loss of Greg Tate, who wrote pioneering, lyrical essays and criticism for the Village Voice, gives us occasion to assess the evolution of the genre he and a handful of other talented Black writers transformed in the 1980s.

Tate, who died Dec. 7 at age 64, did for Black culture what Galileo did for the sun: He put it at the center of the universe. Whether he was writing about film, literature, music or pop culture, he made us the Big Idea to contend with, rather than an ornamental signifier of Blackness relegated to the footnotes. And around that center spun, well, everything. His Voice columns were a masterclass in deploying an insatiable thirst for knowledge to feed associations, connections no reader ever saw coming. (And this was pre-Google!)

It would be inappropriate to call Tate the Dean of Hip-Hop criticism, although he is one of its architects, because Tate wasn’t tethered to genres. Even if you disagreed with his polemical stances, you had to do your homework before stepping in the ring, checking all his sources if you were serious.

His death made me think of what he wrote on Miles Davis’ passing in 1991:

“Pronouncing the death of Miles Davis seems more sillyass than sad. Something on the order of saying you’ve clocked the demise of the blues. . . Miles is one of those works of art, science, and magic whose absence might have ripped a chunk out of the zeitgeist big enough to sink a dwarf star into.”

Greg Tate, who has died at age 64, brought rigor, energy and a polymath intelligence to writing about hip-hop and much more.

It was that alchemy of poetry, vernacular speech and cosmic awareness that made him one of our great bards, on the same plane as Toni Morrison, James Baldwin and Amiri Baraka. It is fitting in a way that he did not die alone — that in that cold month we collectively mourned not only Tate but also bell hooks, Sidney Poitier and what felt like a phalanx of Black excellence following him into that unknown country on the other side.

It feels safe to say that whole careers wouldn’t have existed without Tate and a couple of his peers. Mark Anthony Neal, James B. Duke distinguished professor of African and African American Studies at Duke University, says it was Tate at the Voice and Nelson George in Billboard magazine that taught him what cultural criticism was. “Because I had Greg and Nelson as models, I recognized that I could make a living doing this and bringing some of Greg’s [writing] style into the academy,” he said.

The writer and activist Kevin Powell calls Tate “one of my literary superheroes. As a young writer, I read him religiously. I loved Richard Wright and James Baldwin, but they were dead. Amiri Baraka was alive, but he was … an elder. Greg Tate was immediate, accessible, younger, hip, cool… one of the things I learned from him is that you have to be a student of the world and integrate it into your writing.”

Powell’s invocation of those other names reminds us that while Tate was a star — something I would never dispute — what made him important was that in the firmament of Black thought, he was part of a constellation. Or in literary terms, a tradition. Baraka was heavily influenced by W.E.B DuBois and Black music. During readings, he freestyled bebop between poems. His classic text, “Blues People,” was — and still is — a blueprint for music critics.

Tate studied that blueprint; he knew that whenever our music changed, our material conditions changed — from work songs on the cotton fields to the blues to R&B to rock ‘n’ roll to hip-hop. Tate was simply elevating the latest iteration of popular Black music from a purported nuisance to an artform.

It follows naturally that the tradition continues, that Tate was not the last star in the firmament. So many tributes have already asserted that there will never be another Greg Tate — another position I won’t dispute. But who is the new standard-bearer; who is carrying his tradition of breaking traditions, refusing to tick the boxes and bursting forth with something new?

I have a candidate. Hanif Abdurraqib, the author of five books, two collections of poetry, and three works of nonfiction, is the literary heir to Greg Tate. Like Tate, Abdurraqib is a fellow Ohioan. Unlike Tate — and perhaps this owes to some incremental progress in the world — he is already winning broader acclaim; his pan-cultural 2021 book, “A Little Devil in America: In Praise of Black Performance,” was nominated for both a National Book Award and a National Book Critics Circle Award. (Winners of the latter will be announced Thursday.)

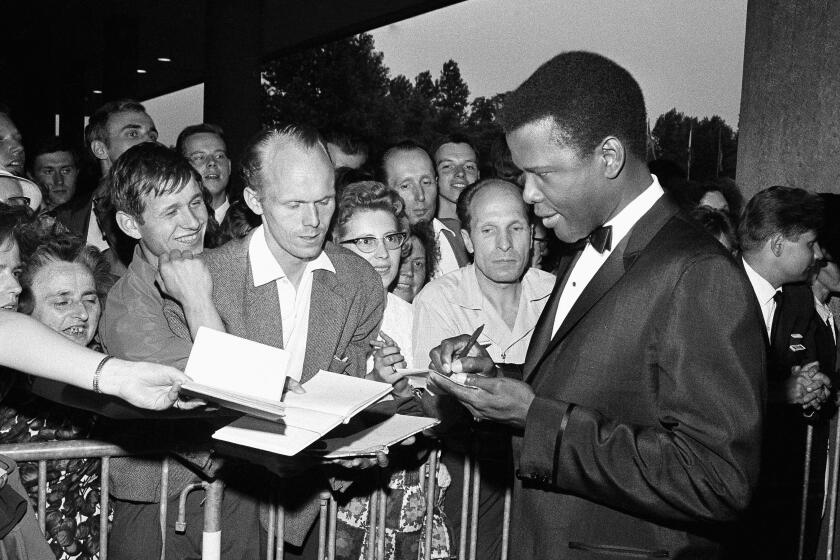

The actor who helped break down Hollywood’s onscreen color barriers before becoming one of the top box-office draws of the 1960s has died at 94.

Abdurraqib’s poems and essays are marked by their masterful use of scenes and pauses. Never is he not his complete, vulnerable self on the page. Even in his author photos you can see a Black man in full possession of himself, rocking skate-boarder sartorial choices. He’s unapologetically Midwestern, Punk, Emo. I can’t imagine his necessary voice without Greg Tate’s.

Abdurraqib’s 2019 book, “Go Ahead in the Rain,” displays his mastery as a poet, spinning lyrical sentences like gold thread. As a critic, he sees and contextualizes without sentimentality. In a marvelous paragraph that closes the first chapter, he weaves cultural and personal history together with such style and feeling that you can only think of Tate:

“So this is the story of A Tribe Called Quest, proficient in many arts but none greater than the art of resurrection,” he begins, documenting their explosive popularity and then panning out: “Here, a story begins even before jazz. Like all black stories in America, it begins first with what a people did to amend their loss in light of what they no longer had at their disposal. With an open palm against a chest, or a closed fist against a washboard, or a voice, echoing into a vast and oppressive sky, or an album teeming with homages — here is the story of how, even without our drums, we still find a way to speak to each other across any distance placed between us.”

I confess I found myself getting emotional reading these words, stung as if by a papercut, in that I only registered pain a moment after I’d finished reading.

Abdurraqib, however, was just getting started. A 2021 MacArthur fellow, the editor at Tin House and the writer-in-residence at Butler University, he is well poised to pass down the tradition of DuBois, Baraka and Tate essay by essay, student by student.

“A Little Devil in America” is probably the most autobiographical of his books, weaving his life stories into meditations on dance. It seems at first a curious choice of subject, until dance becomes both a thematic through line and ultimately a form of narrative. What we get is a contemporary “Souls of Black Folk” opening up into the Black cultural multiverse. Abdurraqib plumbs performance in topics like death and ritual; Aretha Franklin; blackface; Whitney Houston; Black people in space; Josephine Baker; spades; Beyonce; Mike Tyson. He charts his own playlist, a new cultural geography of the Black experience.

‘Didn’t We Almost Have It All,’ by Gerrick Kennedy, casts Whitney Houston in a warmer light and asks: What if she had come up in a more tolerant era?

And in time, his work will be another time capsule, another mark on the journey toward whatever and whoever comes next. Abdurraqib’s closing line in “Go Ahead in the Rain” could very well close a piece about the legacy of Tate and the one Hanif is building.

“When the time comes for the generation after mine to talk about what’s real,” he writes, “they’ll pull a Tribe CD out of their pockets, worn down from a decade’s use and perhaps an older sibling’s. I hope they’ll put it in a CD player and let the room be carried away.”

Ali is a poet and essayist living in Baltimore.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.