- Share via

On the Shelf

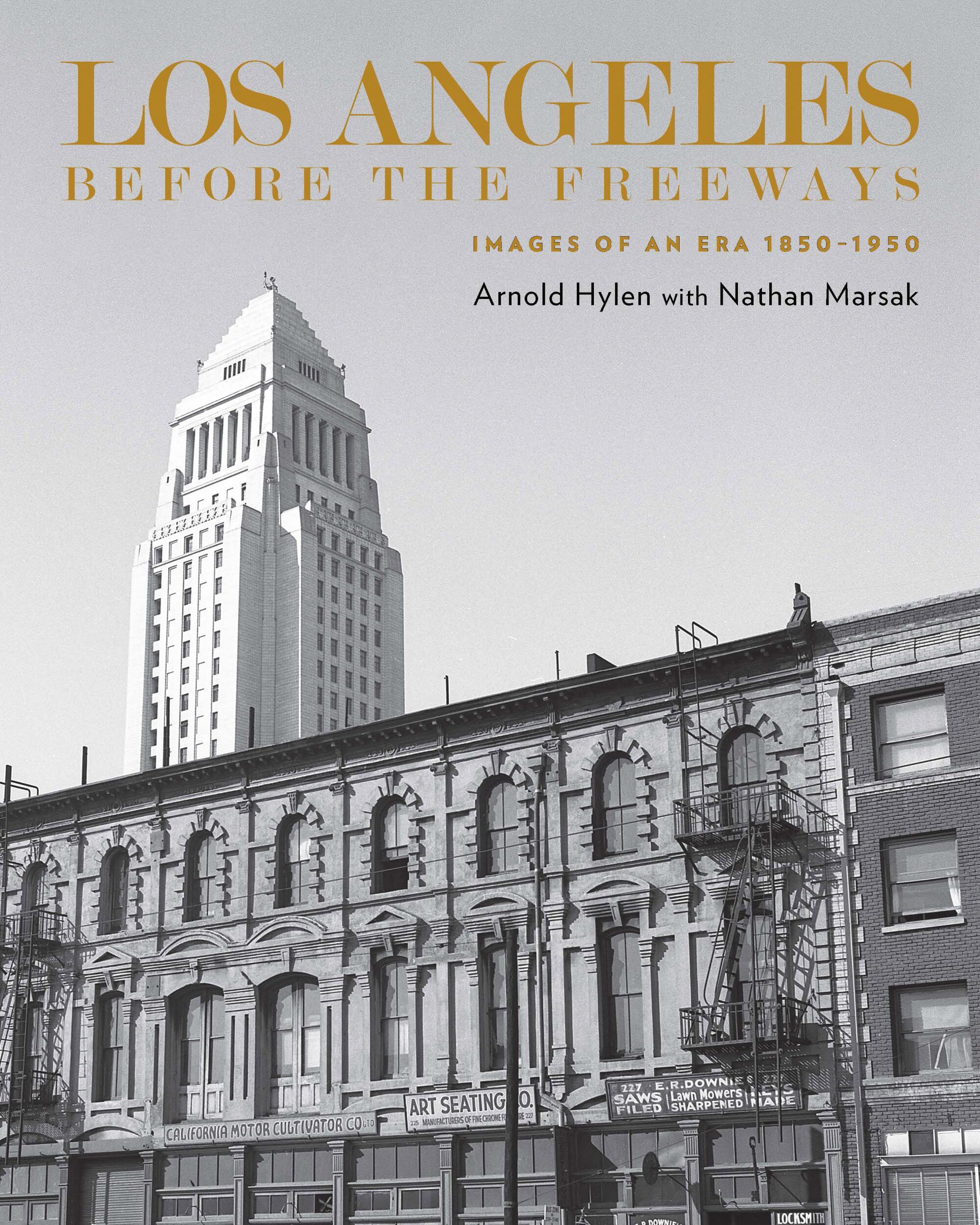

Los Angeles Before the Freeways: Images of An Era 1850-1950

By Arnold Hylen with Nathan Marsak

Angel City Press: 192 pages, $45

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Not long after his arrival in Los Angeles three decades ago, Nathan Marsak bought a 1949 Packard, the kind of car best suited for old-timey gangsters and detectives, not an architectural historian who left Wisconsin to move to the city of his dreams. But he wanted to live “the L.A. noir life,” he says, and no other vehicle seemed more appropriate.

“The L.A. bug just bit me. I wanted to look for the world of James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler, and I did,” he says. “I drove my Packard around, looking for signs of the old, decrepit, dissolute Los Angeles, and I found it in spades. I had lots of adventures.”

From the old suits he wears to the big Highland Park house where he lives with his family, Marsak has a deep affection for vintage things. (He does have an iPhone, though, and his wife did talk him into a microwave — but the design had to be retro.) Marsak’s affection for the past extends to Arnold Hylen, a solitary, mild-mannered Swedish émigré, whose book of mid-20th century photos and an essay about old Los Angeles, “Los Angeles Before the Freeways 1850-1950: Images of an Era,” was recently reissued by Angel City Press in a new edition curated and expanded by Marsak.

Not merely a facsimile, the new edition has been augmented with additional text, notes, fresh layouts and more Hylen photos of an old city on the verge of being swallowed up by the new — a process of cultural erasure that crops up in many criticisms of Los Angeles as a superficial place with no deep sense of itself. Marsak disagrees — sort of.

“It’s deserved, and it’s undeserved,” he says. “I’ve been all over, and it’s unfair to pick on Los Angeles alone. But I think the city’s been an easy target just because we’ve had so many high-profile losses of distinctive architecture here. That stands out in people’s minds. Hylen was certainly aware of those losses and they worried him. If they hadn’t, I don’t think he would’ve felt an obsessive drive to chronicle the old city.”

Hylen lived a quiet bachelor life, Marsak says, and never imagined his photos would one day be among those by William Reagh, Leonard Nadel, Theodore Seymour Hall and Virgil Mirano. He was born in 1908 and arrived in Vermont from Sweden when he was still a baby, relocating to Southern California with his family in 1917. As a teen he studied art at the Chouinard Art Institute in L.A.’s Westlake neighborhood and found work in World War II as a photographer and designer of sales materials and trade show exhibits for Fluor Corp., an oil and gas engineering and construction firm.

As he photographed refineries, his eyes opened to the surrounding city. As Marsak describes in the book’s introduction, he’d “spend the day walking the streets, camera in hand, which fed his interest in the fast-disappearing downtown area, Bunker Hill in particular.”

“I think he knew the value absolutely of what he was doing for himself and other like-minded spirits,” Marsak says, “but I don’t think he knew what to do with the photos.”

Thankfully, Glen Dawson did. An iconic figure in L.A.’s literary landscape, Dawson used his small press to publish two books of Hylen’s photos. Marsak learned about them (thanks to an enthusiastic barfly he encountered in an L.A. dive) and found both in the used bookstores once existing on 6th Street: “Bunker Hill: A Los Angeles Landmark” (1976) and “Los Angeles Before the Freeways,” the latter published not long before Hylen’s 1987 death. Marsak spent many years persuading the photographer’s relatives to sell him the rights to republish Hylen’s work — selling his beloved Packard to fund that purchase.

- Share via

Los Angeles Before the Freeways was originally published in 1981, then went out of print.

Marsak’s dedication has paid off: “Los Angeles Before the Freeways” is an engrossing collection of black-and-white images of a city in which old adobe structures sit between Italianate office buildings or peek out from behind old signs, elegant homes teeter on the edge of steep hillsides, and routes long used by locals would soon be demolished to make room for freeways. These images are accompanied by Hylen’s book-length essay, which runs like a documentarian’s voice-over throughout the collection.

Two notable changes for this edition: More photos and the decision to use Hylen’s uncropped photos, which provide a richer sense of locale and more photos. There were 116 photos in the original book; Marsak went through Hylen’s negatives and found more photos, resulting in 143 images in the new edition.

Marsak supplies an introductory essay and an invaluable guide to the many architectural styles belonging to L.A.’s past. His footnotes and captions also enhance our understanding of the photos: In some cases, he uses them to correct some false claims that Hylen makes in his essay (for instance, that a long stone trough on Olvera Street was a Gabrielino relic when in fact it was actually created by a local rancher).

There are no special effects or gimmicks to Hylen’s photos, no staging or posed imagery — he lets these forgotten edifices speak for themselves. They range from the magnificent, Romanesque detailing of the Stimson Block (the city’s first large steel-frame skyscraper on Figueroa Street) to the multi-gabled, Queen Anne charm of the Melrose, a home built on Bunker Hill by a retired oilman.

Occasionally, though, Hylen’s lens does give us something a bit more impressionistic and emblematic of his thesis about L.A.’s vanishing history. Take, for example, a photo of the Paris Inn on East Market Street. The little French-style inn, which opened in 1930, stands in sharp relief in the foreground while City Hall hovers like a faint ghost in the background, suggesting that a more modern version of L.A. is on the verge of materializing out of thin air.

For Marsak, who spends his time researching old L.A., giving lectures, serving as an Angels Flight operator and working with local preservationist groups, Hylen’s work fills an important gap in L.A.’s past. He hopes readers, especially Angelenos, will come away with a deeper appreciation for their city.

“There’s a saying that when something’s gone, it’s gone for good, and 98% of the stuff in this book is gone,” he said. “Anyone who looks at this book probably already has a preservationist impulse, but if they don’t, if I can light the preservation fire under at least one of them, all the hard work will have been worth it. I really hope seeing this work will make Angelenos think more about their own neighborhoods. I think Hylen would appreciate that.”

Nathan Marsak on 'Los Angeles Before the Freeways'

Marsak will speak about the book as part of the Marie Northrop lecture series for the Los Angeles City Historical Society

Where: Taper Auditorium at the Central Library, 630 W. 5th St.

When: 2 to 4 p.m., June 8

Info: https://www.lacityhistory.org/events/2025/06/08/los-angeles-before-the-freeways-images-of-an-era-1850-1950-with-nathan-marsak

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.