Netflix’s bad week shows the challenges of the streaming business

- Share via

Welcome to the Jan. 25, 2022, edition of the Wide Shot, a newsletter about the business of entertainment. If this was forwarded to you, sign up here to get it in your inbox.

People know the streaming business is hard. So when Netflix reported subscriber additions that missed projections and said its growth would slow down significantly in the current quarter, Wall Street was super chill about it.

Yeah, right.

Netflix’s stock tanked 22% on Friday after the Los Gatos streamer reported disappointing subscriber numbers and projections, wiping out almost $50 billion in market value. It continued to slide Monday, dropping $10.35, or about 3%, to $387.15.

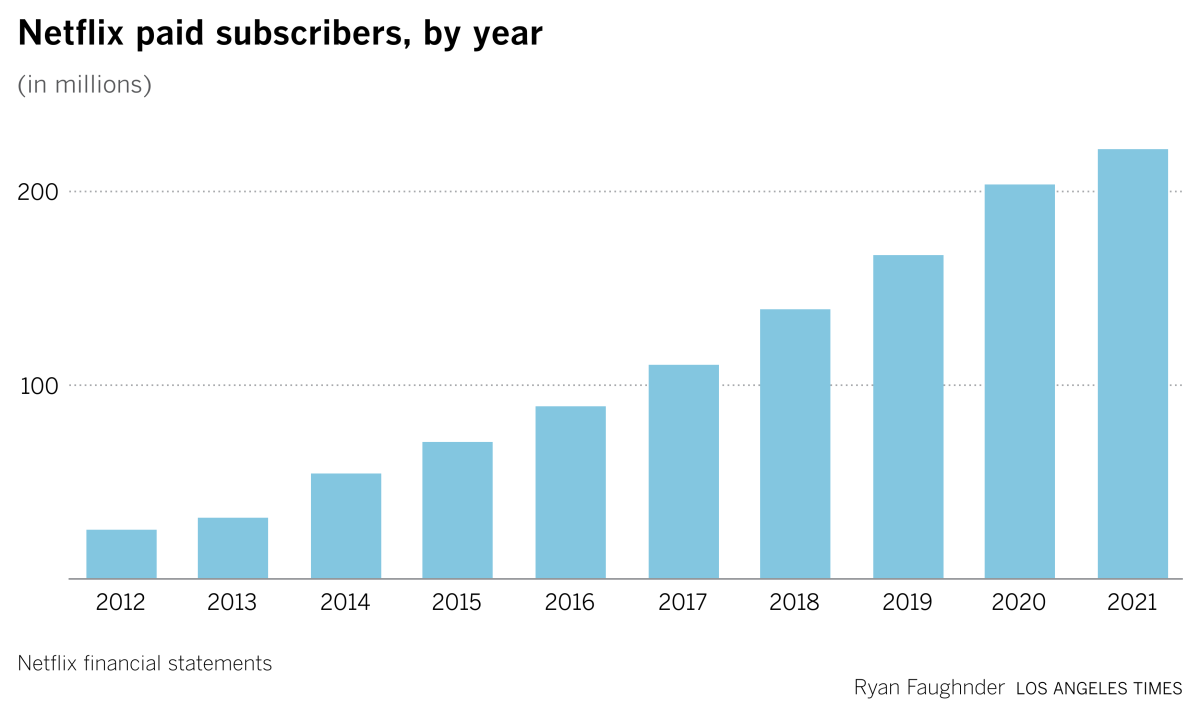

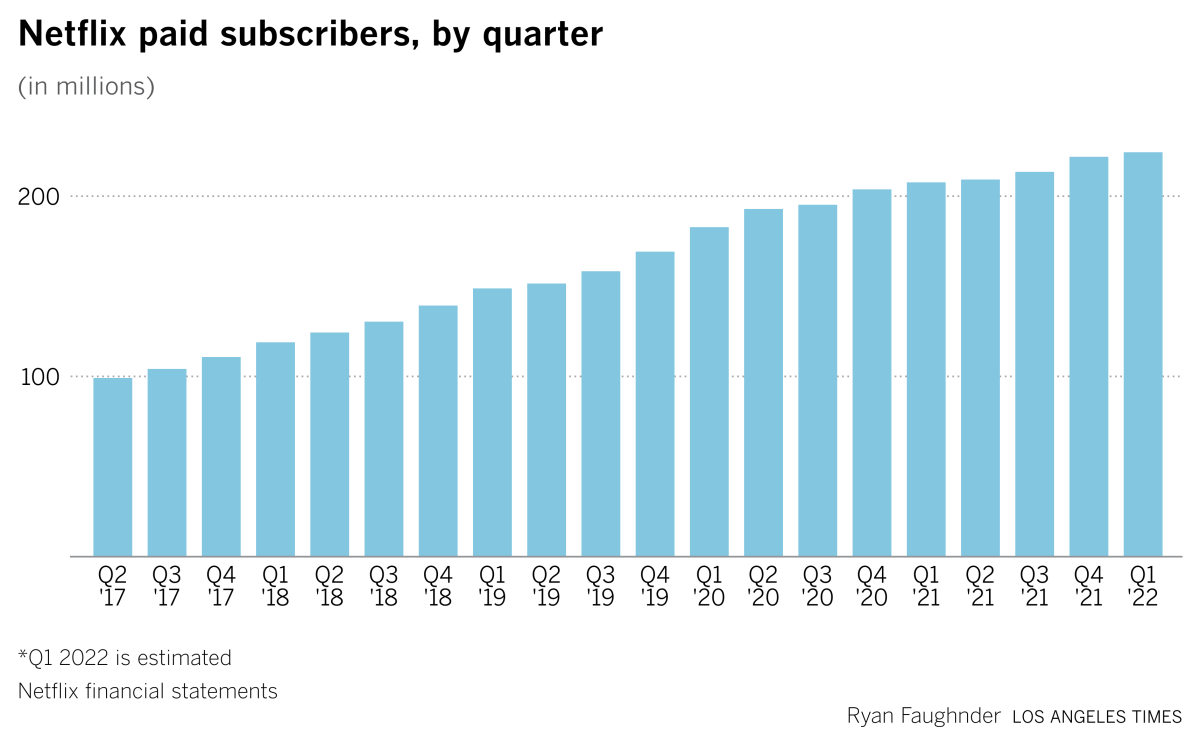

This, of course, happened after the company said it expects to add just 2.5 million subscribers worldwide in the first quarter in of 2022. During the fourth quarter, Netflix grew by 8.28 million subscribers, slightly shy of the 8.4 million analysts had expected.

One quarter doesn’t usually mean all that much, but the numbers are the latest sign that Netflix’s growth is tamping down. This probably shouldn’t be surprising. Netflix and other streaming services enjoyed a big boost in signups during the pandemic, and that effect was bound to wear off at some point, even with the recent COVID-19 surge.

But there might be reasons for the slowdown other than the waning effects of the pandemic — and that has investors skittish.

First, Netflix is facing a lot more competition, with Disney+ and HBO Max trying to grow their subscriber counts and spending billions of dollars to do it. Analysts have long said that people will only be willing to pay so many monthly fees for entertainment, and the industry may be hitting that wall.

Netflix executives tend to say that their biggest rivals are video games and sleep, rather than other streamers. They’ve previously cited Nielsen data showing streaming’s relatively low share of total U.S. TV viewing — 28% compared to cable’s 37% — as evidence that the business has room to grow.

Executives actually acknowledged the increased competition this time when discussing the firm’s earnings, while still kind of downplaying it. “There’s more competition than there’s ever been,” said co-Chief Executive Reed Hastings in a prerecorded video interview. “But we’ve had Hulu and Amazon for 14 years. So it doesn’t feel like any qualitative change there.”

With its 222 million global subscribers, it’s possible that Netflix is getting close to market saturation, meaning it’s only ever going to get so big. It’s already pretty much there in the U.S. and Canada, where it added 1.28 million subscribers during all of 2021. More than 90% of its subscriber growth was international last year, compared to 83% during 2020.

In total, Netflix added 18 million subscribers in 2021, less than half of the 37 million it brought in during the year before. During the past five years, Netflix has added an average of around 27 million subscribers annually.

Netflix executives seemed a little stumped about the drag on growth. “It’s tough to say exactly why our acquisition hasn’t kind of recovered to pre-COVID levels,” said Chief Financial Officer Spencer Adam Neumann during the video.

The more interesting thing about Netflix’s earnings report, though, is what it says about the challenges of the streaming business in general. A couple weeks ago, we borrowed a theme from analyst Michael Nathanson when we asked, “are we sure streaming is a good business?” I didn’t expect to come back to this so soon, but here we are.

Nathanson, in a report, called Netflix’s quarter “a worrying data point for the rest of the streaming industry on multiple fronts.”

Netflix had a very strong (and expensive) content lineup last year, with its two most-watched movies ever in “Red Notice” and “Don’t Look Up,” a game-changing international series in “Squid Game” and the return of older faves like “The Witcher.” What happens when the shows aren’t as compelling and there’s a not a pandemic raging?

Because of the audience’s appetite for new shows and the speed at which we binge them, streamers are spending more and more to produce and acquire content.

But that spending eats into Netflix’s financial results. Free cash flow was negative in 2021 (-$159 million on nearly $30 billion in revenue, compared to positive cash flow of $1.9 billion the year before). The company said it expects to be cash-flow positive this year and beyond, which executives say proves its business model is solid.

The streamer spent $17 billion on content last year and is expected to spend about $19 billion in 2022, Nathanson estimates.

Still, competition is too high for Netflix to cut spending. Raising prices too quickly carries the risk of subscriber churn. Netflix recently hiked the monthly fee for its standard plan by $1.50 to $15.49.

There are signs that investors think the streaming difficulties are not just a Netflix problem. Shares of Disney, Roku and ViacomCBS also fell on Friday amid a broader market selloff.

Streaming video is basically all Netflix does. If it’s this tough and expensive for Netflix to keep growing, it’s probably not going to be any easier for Disney, WarnerMedia, Discovery or ViacomCBS. Imagine what it means for companies that also have to try to run theme parks and maintain cable channels.

Netflix doesn’t even have to worry about how much streaming is cannibalizing revenue from old businesses like box office sales and cable advertising. Disney and its ilk do.

Netflix may be entering a period of slower growth for a while. That might mean analysts will put more emphasis on profits than they did during the years of torrid expansion. That’s not necessarily a bad thing for Netflix. But it means people will be looking at Netflix’s business differently.

Sundancing in the dark

“Flip it to a streamer” has become the go-to cliché of independent film financing, and it’s easy to see why.

With the box office for art-house cinema in a precarious situation, investors need some kind of justification for putting money into the types of films that populate the Sundance Film Festival, which kicked off virtually last week. Their best bet to recoup their investment is to sell to a streaming service like Netflix or Apple.

Now one of Hollywood’s top financiers says he doesn’t want to back indie movies made exclusively for theaters. Jason Cloth, the chief executive of Creative Wealth Media, knows many filmmakers and producers want to see their work on the big screen and believe their picture is the next “Little Miss Sunshine.” It’s just not a good bet for his business. (Here’s our full story.)

“I need to understand what everyone’s thinking in terms of exit before I’m comfortable putting up money,” said Cloth, who has backed movies such as “House of Gucci,” “Licorice Pizza” and the upcoming “Cyrano.” “And now, I’m not all that comfortable seeing independent film pitched to me with a theatrical exit, and I’m quite vocal to people, telling them, ‘I think you’re delusional.’”

The streaming services have been the ones able to write big checks for independent productions. Apple paid a record $25 million last year for the comedy-drama “CODA,” which is getting Apple TV+ into the Oscar conversation.

For Apple, which can spend $200 million on a Martin Scorsese film without blinking, it might be worth it to get the prestige and the bump in Apple TV+ subscribers a big film can bring. The major tech companies may eventually curtail their spending on movies, but for now they’re the buyers most willing to throw around silly money.

“It’s hard to compete against somebody that is really acquiring these things for other purposes than to make money,” Cloth said. “When your motivation is financial, then you cannot compete against somebody whose motivation isn’t.”

Stuff we wrote

— Pay TV operators are dropping Trump-loving cable networks. Far-right channels One America News Network and Newsmax are losing distribution. Pay TV providers say it’s not politics that drove their decisions, but the upended economics of their business.

— Disney rejiggered its streaming leadership. Michael Paull will oversee Disney+, Hulu, ESPN+ and Star+. Joe Earley was named Hulu’s new president. Also, CEO Bob Chapek’s pay doubled to $32.5 million as cash bonuses returned to Disney’s top executives. But former executive chair Bob Iger actually make more money than Chapek, with a $45.9-million compensation package.

— YouTube is retreating from the original programming business. Susanne Daniels, its global head of originals, is resigning. I’m constantly having to remind myself that “Cobra Kai,” now a big hit for Netflix, was once a YouTube Original.

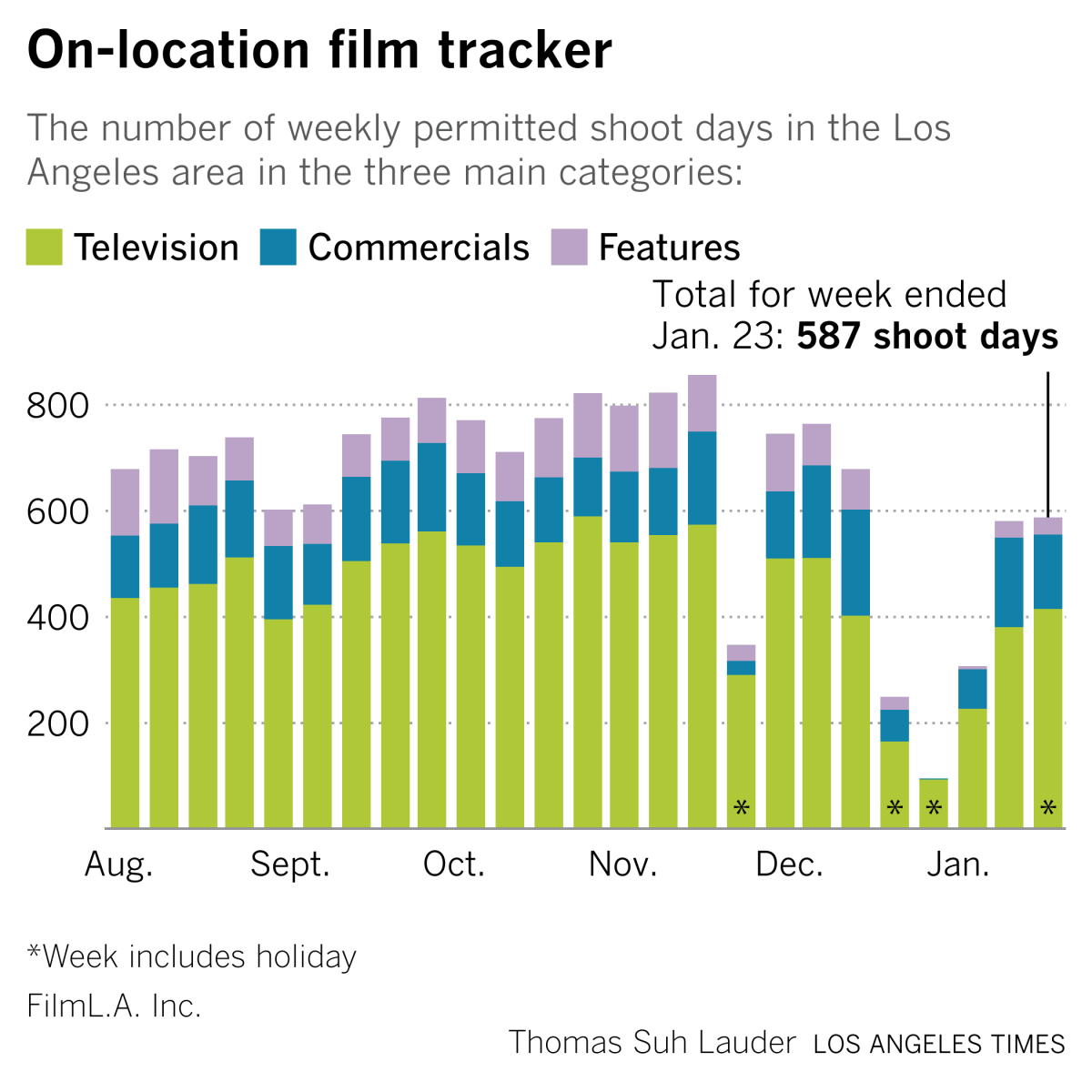

— FilmLA reported a record quarter for production in Los Angeles. But data for the full year reflected a more complex narrative for the business of local film and TV production, with uncertainty continuing into 2022. While 2021 generated 37,709 shoot days, up about 3% from the pre-pandemic year of 2019, film activity in 2021 was down 1.6% from the average of the four years preceding the pandemic, FilmLA said.

And the numbers were grim for feature films. Last year ended with a total of 3,406 shoot days for features, down 19% from the annual pre-COVID-19 average, FilmLA reported.

On the bright side, television contributed a record 18,560 shoot days for the year, up 37% from 2019. In fact, nearly half of the shoot days recorded by FilmLA last year were for television production, the group said.

Here’s our weekly production chart, which shows that shoot days so far this year may have been affected by delays due to the Omicron variant.

Number of the week

Especially compared to box office, video games are huge. Video game content sales are expected to surpass $200 billion this year, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. Worldwide movie ticket sales peaked just above $42 billion before the pandemic did its thing.

Xbox generated more than $15 billion in revenue for Microsoft in fiscal 2021, and the Redmond, Wash., tech behemoth wants to get even bigger in the space. It’s buying “Call of Duty” maker Activision Blizzard for nearly $69 billion.

Yes, this is about consolidating power in the gaming industry. Take-Two Interactive just announced its deal to buy “FarmVille” creator Zynga earlier this month.

Also, Microsoft wants to grow its Xbox Game Pass subscription business, which has about 25 million accounts, and content from Activision Blizzard could help. At the same time, Microsoft has its eye on the hypothetical virtual reality shadow economy known as the metaverse.

I know. When executives talk about the metaverse, it can sound like they’re just latching onto the latest buzzword. NFTs, crypto, sure, whatever. But in the world of video games, the metaverse talk makes more sense. The gaming industry has had online universes for years through roll-playing hits like “World of Warcraft,” another Activision franchise.

Microsoft’s deal was opportunistic. Activision’s stock has been depressed amid a workplace scandal. California regulators sued the Santa Monica company last year over sexual harassment and discrimination claims. The Wall Street Journal reported in November that Activision CEO Bobby Kotick knew about allegations of employee misconduct that he didn’t tell the board about, sending shareholders running. Kotick has disputed many of the allegations.

There’s no guarantee this deal happens, with U.S. regulators looking to apply increased scrutiny to big mergers. Gaming rival Sony Corp.’s stock plunged on the news, in a sign that the market sees the deal as a serious problem for Activision’s competitors.

People have speculated about Amazon’s $8.45-billion purchase of MGM getting blocked. The Microsoft-Activision one is eight times that size.

You should be reading...

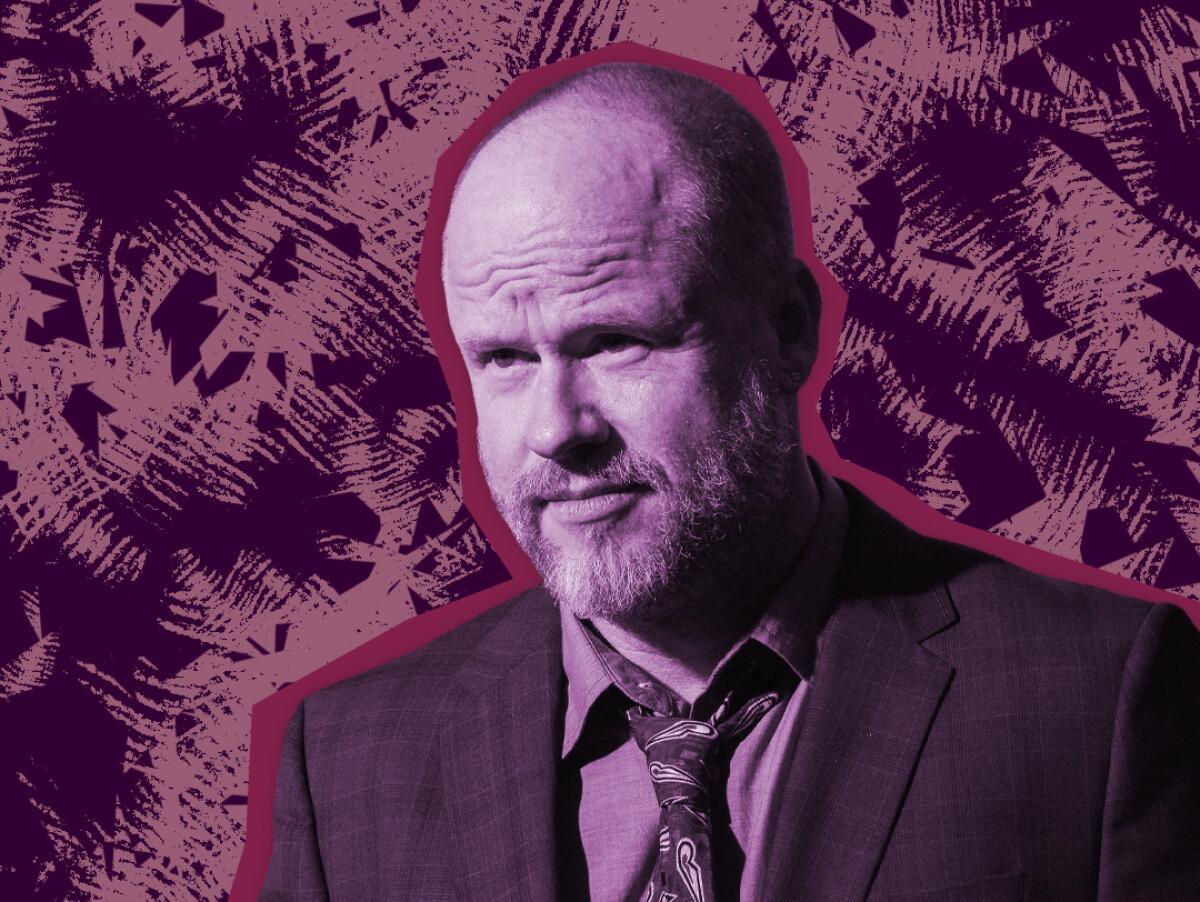

— The undoing of Joss Whedon. The “Buffy” creator, once an icon of Hollywood feminism, is now an outcast accused of misogyny. How did he get here? (Vulture)

— What the kids are reading. Paul Musgrave wrote an interesting analysis of the new generation and its media consumption. (Substack)

— Kathy Griffin is trying to get back on the D-list. Ever since her Trump joke went wrong in 2017, Griffin has been seeking a professional rebirth and wondering who among the canceled gets a second chance. (New York Times)

— The future of agenting isn’t in Hollywood. Take it from United Talent Agency head Jeremy Zimmer. (Vulture)

Finally ... sound and fury

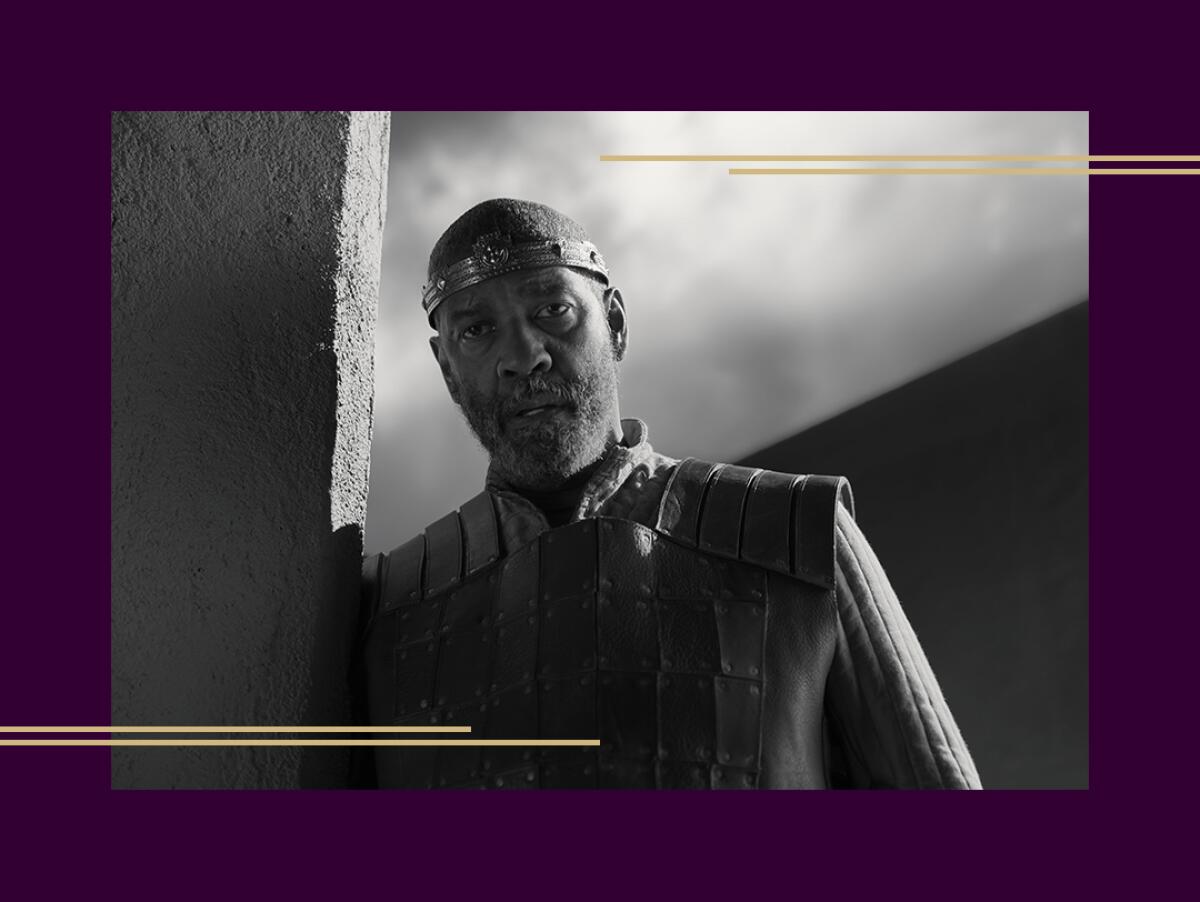

I watched Joel Coen’s “The Tragedy of Macbeth,” and seeing Denzel Washington’s take on the Scottish play was everything my inner English major wanted. But my favorite viewing decision was immediately streaming Akira Kurosawa’s “Throne of Blood,” the Japanese legend’s samurai Shakespeare adaptation. What a finale!

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.