The Cure’s Robert Smith: ‘The ’80s were awful, and yet we flourished’

- Share via

Few years have been as confounding to the Cure’s Robert Smith as 2019. The British alternative rocker often jokes that the band’s four-decade career has come in spite of his best efforts to be dark and contrarian, but the accolades have only accelerated, including the Cure’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in March.

“Sometimes when you’re feeling miserable and you listen to miserable music, it comforts you, because you feel there’s someone who understands. You’re not alone,” says Smith, who turned 60 in April.

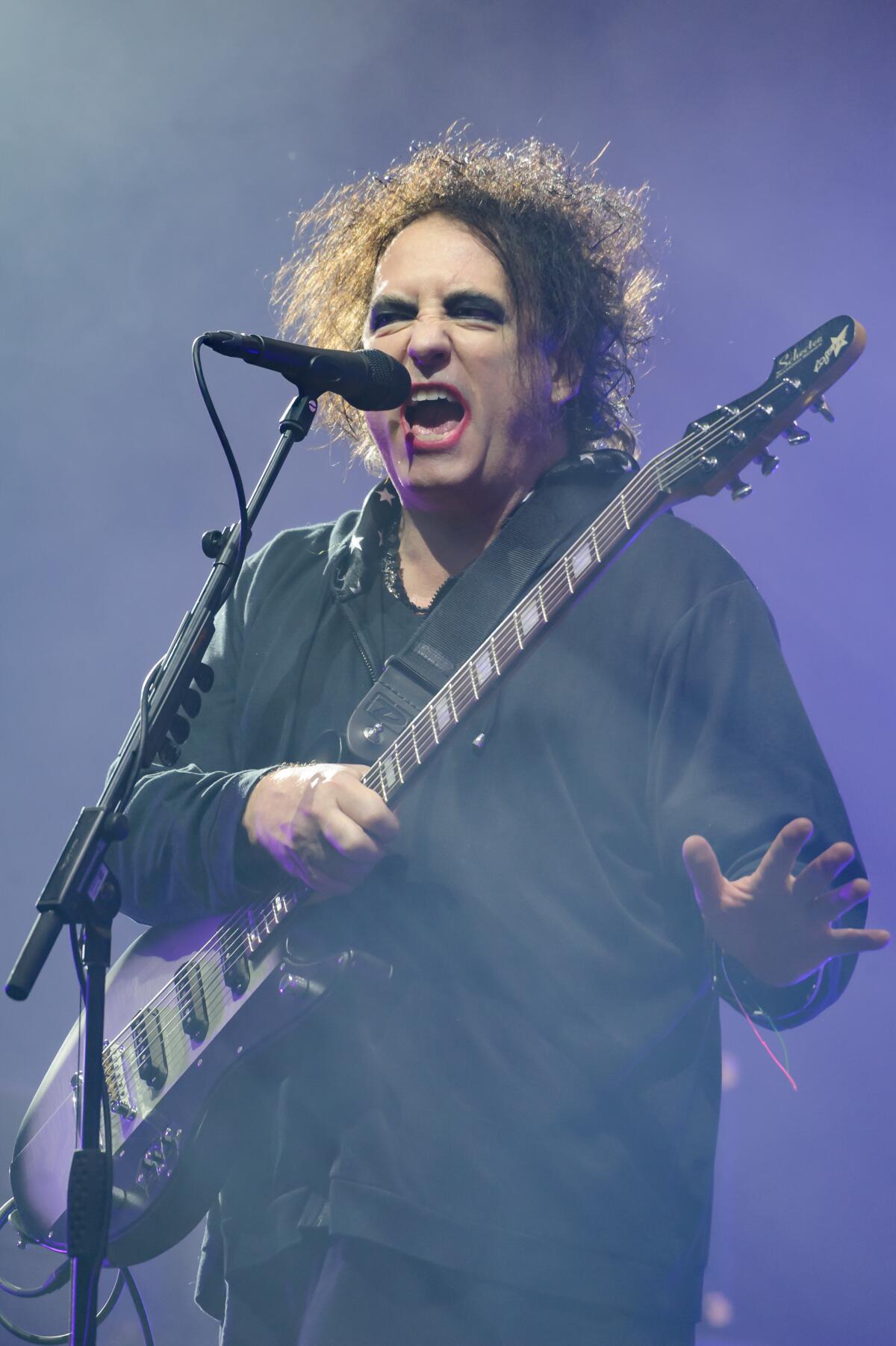

In smeared lipstick, eyeliner and an eruption of unkempt black hair, Smith has been rewarded with a career of platinum record sales and stadium crowds for music of playful melodies (“The Love Cats”) and angsty, Gothic gloom (“Disintegration”). That history is being celebrated on the Cure’s summer tour, which ends Saturday with the Pasadena Daydream Festival, curated by Smith himself.

The Cure will be joined at Brookside at the Rose Bowl with an eclectic lineup of “fantastic live bands,” he says, including the Pixies, Deftones, Throwing Muses and Chelsea Wolfe, among others.

Smith spoke with The Times from his home near Brighton, England, before heading to France to perform two hours of songs lovesick and atmospheric, morose and fitfully hopeful, which the Cure’s audience has dependably embraced since the early 1980s.

“The best part about playing live is seeing how weird the audience has become,” he says. “The less mobile people with gray hair in the back, and down in front the people with glitter on their faces.”

What satisfaction do you get as the curator of a music festival?

Last year’s annual Meltdown Festival in London was 10 days and three venues, between six and 10 bands on every night. And I picked them all. It’s like a teenage dream, isn’t it? I’m trying to achieve — it’s very old fashioned, I suppose — a sense of community.

Do you still identify with the original punk and post-punk movements that first inspired you?

I still feel the same kind of frustrations as I did when I was at that age about how things are done, not just in the music business but the world in general. The ‘80s were particularly awful, and yet we flourished in it because we represented an alternative. Corporate greed became rampant in the ‘80s. I still feel angry about that kind of stuff, which is kind of odd because most of the people my age that I was growing up with don’t seem to care that much anymore.

At the Cure’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, Trent Reznor talked about how important your band was to him as a teenager growing up in small town Pennsylvania. Do you feel part of a continuum of artists with a certain point of view?

One of the most gratifying things is when another artist that you admire turns around and says they like what you do. When Bowie told me that he liked what I did, that was it for me. I could have stopped. Quite often it’s not about the music. It’s about how we’ve managed to do what we’ve done in the way we’ve done it. That gives hope to people that there isn’t just one way of doing things. I had heroes like Bowie, Nick Drake and Alex Harvey. I wanted to be distinctive and individual. So if I am part of that continuum, I’m very happy to be.

How far along are you on a new Cure album?

We’re going back in [the studio] three days after we get back from Pasadena for me to try and finish the vocals, which is, as ever, what’s holding up the album. I keep going back over and redoing them, which is silly. At some point, I have to say that’s it.

Has this been in the works for a long time or did you suddenly get to a point where it all came out at once?

I was offered the chance to curate the Meltdown Festival [in London] and I said yes. And then I realized I didn’t really listen to very much new music anymore. So I threw myself headlong into it and started listening to bands again and meeting kids who were in bands, and something clicked inside my head: I want to do this again. It came as a bit of a shock to me, to be honest. No one really believed me until we started recording.

Is there anything from your history that you would compare this new album to?

It’s very much on the darker side of the spectrum. I lost my mother and my father and my brother recently, and obviously it had an effect on me. It’s not relentlessly doom and gloom. It has soundscapes on it, like “Disintegration,” I suppose. I was trying to create a big palette, a big wash of sound.

Do you have a title?

The working title was “Live From the Moon,” because I was enthralled by the 50th anniversary of the Apollo landing in the summer. We had a big moon hanging in the studio and lunar-related stuff lying around. I’ve always been a stargazer.

In the past, when the Cure released an album, you’ve said the band was going to retire. How are you feeling this time?

Being the contrarian that I am, I’d be very unhappy if it was the last one. We’ll be onstage tomorrow and I’ll be saying to them, “This is the last time in Paris,” and they’ll look at me and shrug their shoulders. At some point, I will be proved right.

Pasadena Daydream Festival

Who: The Cure, with the Pixies, Deftones, Mogwai, Throwing Muses, the Joy Formidable, Chelsea Wolfe, the Twilight Sad, Emma Ruth Rundle and Kaelan Mikla

When: 1 p.m. Saturday, Aug. 31

Where: Brookside at the Rose Bowl, Pasadena

Cost: Ticket prices vary

Info: pasadenadaydream.com/

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.