Pedro Bell, artist who created Funkadelic’s cosmic album covers, dies at 69

- Share via

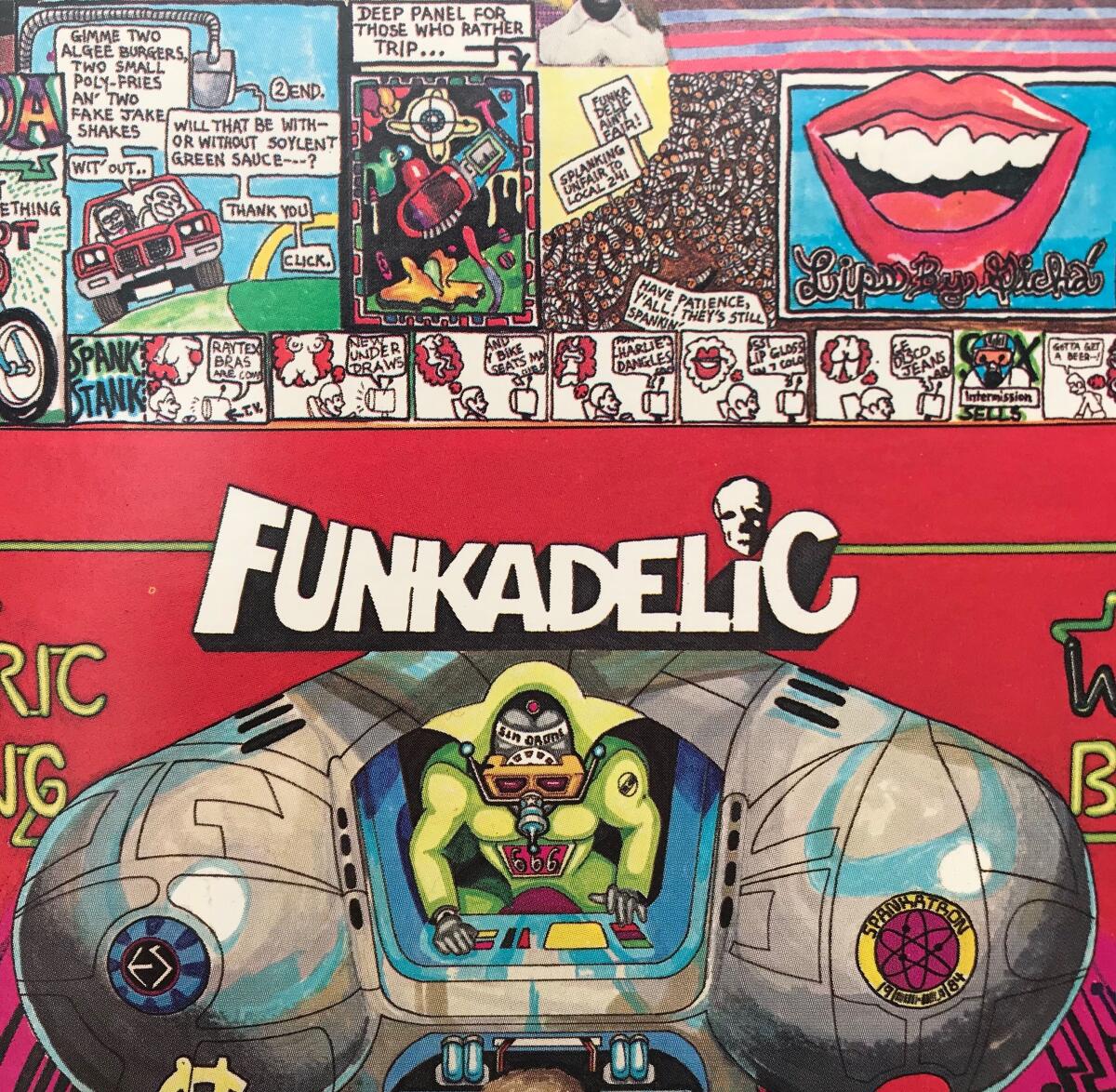

Pedro Bell, whose wild, psychedelic album covers for Detroit cosmic funk band Funkadelic defined the influential group’s aesthetic, died Tuesday. He was 69.

His death was confirmed by longtime Funkadelic bassist Bootsy Collins. No cause of death was given. Funkadelic founder George Clinton acknowledged his collaborator’s passing on Facebook, referencing Bell’s backward-spelled nickname: “RIP to Funkadelic album cover illustrator Pedro Bell. Rest easy, Sir Lleb!”

Starting with the band’s 1973 album “Cosmic Slop” and continuing for the next decade, Bell’s densely populated LP covers were intrinsic to Funkadelic’s landmark concept albums. Musing on identity, commerce, Afro-futurism and sex, Bell mixed comic panels, photo collages, scribbled editorial asides, many aroused phalluses, music criticism, half-invented linguistic flourishes and politically driven invective to create his striking artwork. He captured the band’s wild energy by selling not just music but ideas.

“If you want to survive, you better have some visual concept, and if you really want to survive you better have more than that,” he told an interviewer in 2009.

In Bell’s Funkadelic universe, he wasn’t just an illustrator but an “electric marker heathen of speedomatic dabblings,” as he titled himself on the album “One Nation Under a Groove.” Funkadelic wasn’t a band but makers of “the sabre tooth, slippery tongued & most nastic mau-mau bootybusteroosters of noxious negrow, humpanotical moldy metal marching noise music.” Minutes weren’t measured in seconds but in “alembic time parsecs.”

Born in Chicago into a religious family, Bell’s earliest inspiration arrived during Bible-reading sessions with his father. “He used to read Genesis, and that turned me on to dinosaurs and Godzilla,” Bell said. “I also got turned on to Latin, and that’s where I came up with the idea of having a Rumpasaurus. Revelations was all about the future, which lead me to reading a lot of science fiction.”

Self-taught, Bell got his big break after sending what he described to Juxtapoz magazine as “a hand-designed envelope duplicating a dollar bill with the address where the serial number is supposed to go” to Funkadelic’s manager. The query led to his first project, Funkadelic’s “Cosmic Slop.” Said Bell of Funkadelic’s Clinton, “Back in those days, George knew nothing about UFOs and stuff. In the early ’70s, all that space thang came from me.”

“That space thang” would come to represent Clinton’s musical cosmology, one that celebrated blackness and space travel while mixing pop culture references with op-ed indictments. A small panel on the back cover of “Uncle Jam Wants You” (1979) slammed “Mick Jagoof of the Rolling Drones” for “Miss You” and its “2-D disco-sadistic lyrics of zero groovativity.”

On 1981’s “The Electric Spanking of War Babies,” issued by Warner Bros., Bell attacked the label’s “head spank-chief” on the album cover. That critique stood to reason, though. After promising creative autonomy for the album, Warner Bros. deemed Bell’s artwork too risque for public consumption. Perhaps the company had a point: The cover featured Clinton operating an erect-penis-shaped spanking machine whose subject was a naked woman. In response, Bell altered the album cover to mask the naughty parts and used it as a vehicle to decry the situation. “They paid me to censor the cover,” he told Juxtapoz.

Bell mixed his joyful incitements, though, with urgent calls for action. For decades, read one message on “Cosmic Slop,” “I have gazed upon the so-called highest life form on this planet with unbridled disgust! For the very source of life energies of Earth have become the castrated target of anile bamboozlery from homosapiens’ rabid attempts to manipulate the omnipotent Forces of Nature! Their directionless efforts to achieve the metaphysical state of godliness, eons premature to evolutionary destiny have, indeed, become an invitation to species extinction.”

The artist’s aesthetic made its biggest imprint with Funkadelic and its offshoot band, Parliament, and his collaborations with Clinton continued on the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer’s solo albums, including 1982’s “Computer Games.”

Bell struggled with health issues for decades, but during that time his art became celebrated not just among funk aficionados but in fine art circles. In 2007, his work was featured in a show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.

By the mid-1990s, the artist’s eyesight began to falter; he was legally blind for the rest of his life. Asked by an interviewer about the tragedy of being a visual artist lacking eyesight, he demurred with typical poeticism: “Ain’t no pity in checkerboard city.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.