How a digitized colonial codex reveals fresh stories about Mexican Indigenous life

- Share via

Halloween may be behind us, but I still can’t get enough of La Monja de la Feria. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, art and design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, and I’m here with all the best ghoulish dancing carnival nuns and essential arts news:

Mexico’s lost codex tells so many stories

Its length is exorbitant, the entries dense and the title wildly academic. But “La Historia General de las cosas de la Nueva España” — known as “The General History of the Things of New Spain” in English — is one of the most intriguing historical chronicles to emerge over the last 500 years.

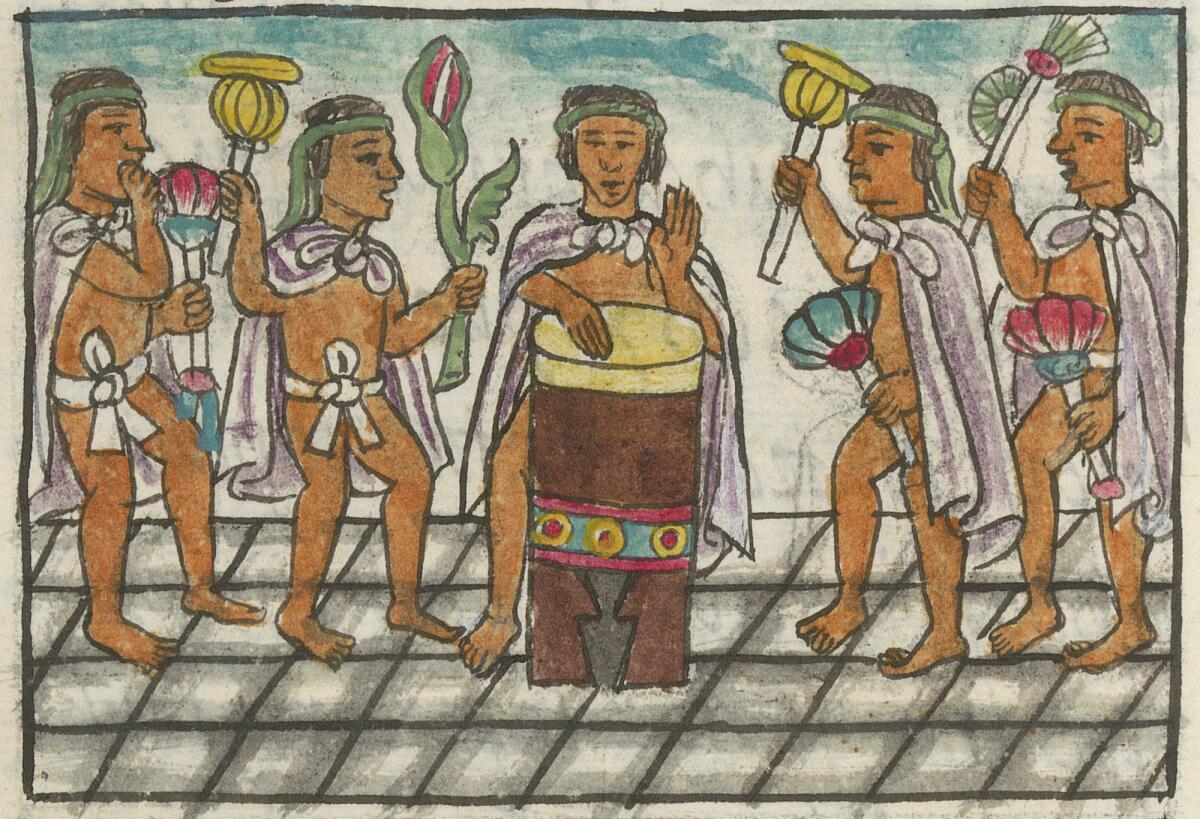

Better known as the Florentine Codex, it is a comprehensive colonial-era record of Mexican Indigenous life at the time of the conquest. And it is written in both Spanish and Nahuatl, the language of the Nahua (also referred to as the Mexica or Aztecs), making it the exceedingly rare chronicle to capture an Indigenous worldview in a Native language during this tumultuous period.

Now, thanks to an effort that was led in part by the Getty Research Institute, the Florentine Codex has been digitized, its nearly 2,500 hand-painted images tagged, so that it is not only broadly available but also easily searchable. “What is so revolutionary in the document,” says Bérénice Gaillemin, a Mexico City-based anthropologist and art historian who has worked on the digitization since 2020, “is being able to provide access to all the document, all the translations, and to understand the images, as well as enjoy the images by themselves.”

The story of the Florentine Codex is as remarkable as the document itself. (I wrote about it back in 2020.) It was conceived by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún and written and illustrated by a group of Indigenous scholars at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco. The aim was to create a compendium of knowledge (like Pliny the Elder’s “The Natural History”), but also a tool that could help the Spanish better understand Nahua culture and, therefore, more easily convert them to Christianity.

But its influence was short-lived — at least initially. Shortly after its creation, the codex was shipped to Spain but somehow ended up in the hands of an Italian cardinal in Rome, who took it to Florence, where it was stashed in the Medici family libraries (likely helping it survive the purges of the Spanish Inquisition). It wasn’t until the late 18th century that the existence of the codex came to the attention of scholars.

Although a scanned version has been available via the World Digital Library since 2012, the tight, hand-written entries are onerous to read, and the antiquated language can be a barrier. The Digital Florentine Codex, as the new online project is called, features the scanned pages, as well as typed transcriptions of the original Spanish and Nahua texts and translations of both into English.

This is critical: Scholarly studies have often focused on the Spanish texts in the book. The Spanish and Nahuatl, however, were not direct translations of each other, but different texts that offered different views. “People only know the Spanish,” says Gaillemin. “But that is only part of the story.”

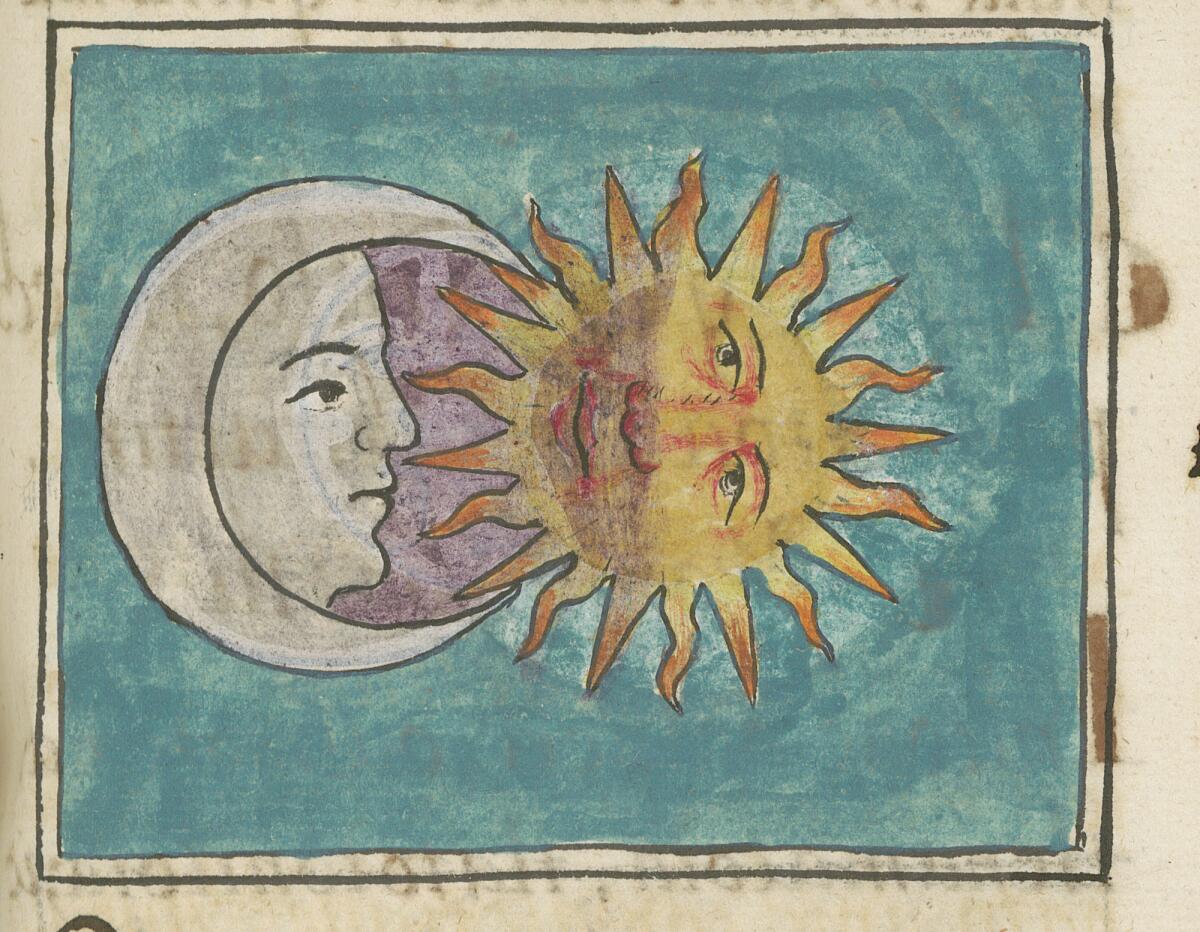

Most remarkable in the new digital version is the prominence of the illustrations. These are a critical component of the books since they offer vital depictions of flora, fauna, craft, ritual and belief. Now each image is tagged in Nahuatl, Spanish and English, making it possible to conduct searches for terms including “dogs,” “dance” and “architecture” across all 12 volumes.

Gaillemin says that during the process she and her fellow researchers were able to conclude that at least 19 painters were involved in the Codex’s production, producing images in a range of Western, Indigenous and hybrid artistic styles.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Most interestingly, many of the artists used logograms (a symbol to represent a word) rooted in the use of homophones. “It’s like, in English, using an eye and a bee and a leaf to say, ‘I believe,’” explains Gaillemin. Except, in the codex, many of these homophones were based on Nahuatl words, requiring knowledge of the language to decipher them.

Gaillemin, who has a deep knowledge of classical Nahuatl, points to an illustration of an aquatic cave that appears in Book 11. Hovering above the cave in the drawing are clouds (mixtli), over which an eye (ixtli) and a cup (tecomatl) have been superimposed. These can be stitched together to form the word “mixtecomac,” which can mean “dark as night.” “The painter picked that one word from the Nahuatl text” to illustrate, notes Gaillemin. “If you just focus on the Spanish translation, you will never understand it.”

The Digital Florentine Codex was a massive undertaking years in the making. (The credits page features dozens of collaborators across institutions in Mexico, the U.S. and Europe.) And it has involved teams of scholars who have brought to the project a profound knowledge of history, natural history, ethnicity and language.

As Gaillemin notes, “there is this fashion with using artificial intelligence to make things searchable.” But the Florentine Codex would have been ill-served by systems dominated by contemporary Western knowledge. “Without someone who is familiar with Nahuatl or with colonial iconography, it’s impossible to understand these images.”

View the codex and search its text and imagery at florentinecodex.getty.edu.

Dispatches from the field

Times art critic Christopher Knight submitted a mini-dispatch after a recent visit to the Skirball:

Immigration, whether voluntary or forced, comes in many varieties. Very different examples are on view in two small new shows, both worth seeing at the Skirball Cultural Center. “Reclaimed: A Family Painting” tracks the remarkable restitution of a German Baroque canvas of “Isaac Blessing Jacob” by Johann Carl Loth, looted by the Nazis when the daughter of Johann and Lisbeth Bloch, a Czech Jewish couple, was forced to flee, her family eventually making its way to Los Angeles. And British artist Yinka Shonibare has assembled a 6,000-volume “American Library” composed of unidentified books wrapped in vivid, Dutch wax-printed cotton textiles, their spines printed in gold with the names of U.S. immigrants and Black Americans affected by the Great Migration.

Find more details at skirball.org.

On and off the stage

Times culture writer Ashley Lee digs into the controversy over “By the River Rivanna” at Santa Monica College, a play by G. Bruce Smith that was canceled hours before it was scheduled to open last month. The play tells the parallel stories of two interracial relationships — one set on a plantation in 1850 between a white male slave owner and an enslaved Black man and another set in the present. “Complaints from students and faculty that the play inappropriately romanticizes the era of slavery” and “an anonymous vote by student participants” put an end to the production, reports Lee, and has led to an examination of how plays are selected.

The Tony-winning musical “Spring Awakening,” about a back-alley abortion gone wrong, grows only more relevant at this moment, writes Times theater critic Charles McNulty. A new production staged by East West Players and directed by Tim Dang brings fresh talent to a show that is “part concert, part drama, part secular mass.”

This week marked the 20th anniversary of WordTheatre and my colleague Steven Vargas sat in on rehearsals for a reading of Margaret Atwood’s “Happy Endings” — featuring Ron Perlman and Sharon Stone. The nonprofit organization brings well-known actors together to stage dramatic readings of literary works. “I want to leave behind great actors reading great short stories,” says founder Cedering Fox, “and I want them in libraries all over the world so people can listen to them for free.”

In and out of the galleries

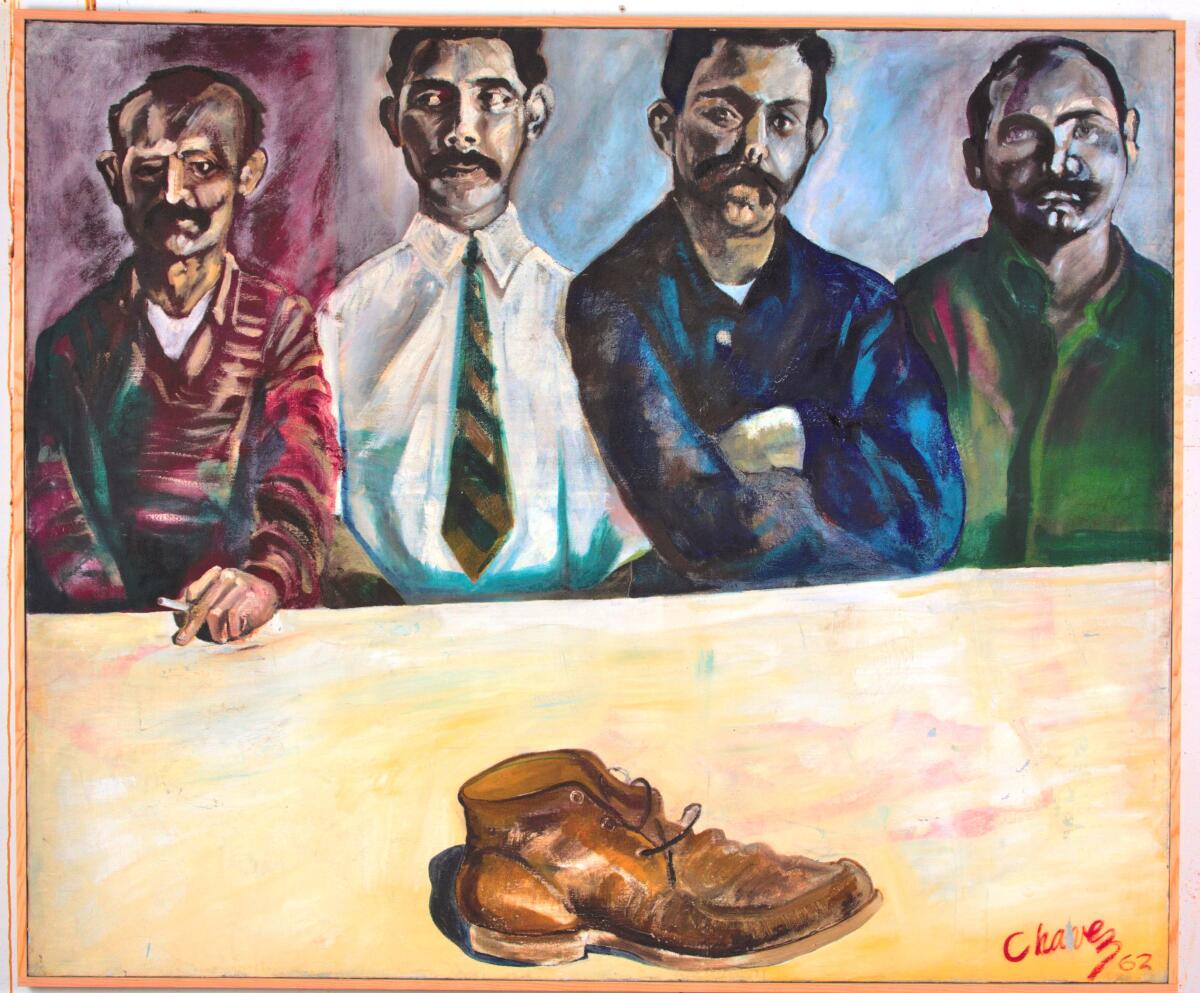

Ceeje Gallery, one of L.A.’s ‘60s-era show spaces, is the subject of a sizable exhibition at the Williamson Gallery at Art Center for College of Design, organized by independent curator Michael Duncan. Founded by Cecil Hedrick and Jerry Jerome, the singular Ceeje (pronounced “see-jay”) occupied a decorative arts shop where a small restaurant was also located. Christopher Knight notes that the gallery foreshadowed today’s art world, showing “perhaps the most diverse range of artists of any gallery at the time in the city.”

The Getty Foundation has announced a series of new grants for five months of public programming for “PST Art: Art & Science Collide,” the next iteration of Pacific Standard Time, scheduled to take place in 2024. This brings the Getty’s investment in the series to $19 million. My colleague Jessica Gelt has the deets.

Rong-Gong Lin reports on how the twin giant rockets of the space shuttle Endeavour are coming together at the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center in Exposition Park. Each weighs 104,000 pounds and is the size of a Boeing 757 fuselage.

Artist and “self-proclaimed all-American Jewish lesbian folk singer” Phranc is opening the doors on a retrospective, “The Butch Closet,” at Craig Krull Gallery. The artist sat down for a Q&A with contributor Candace Hansen to talk about being part of “the queerest band in town” and the scene at the Woman’s Building.

Susan Tallman reviews Ed Ruscha’s retrospective at MoMA in the New York Review of Books. “Retrospectives that span so many decades usually follow a certain arc: skill-building, imitation of admired masters, the finding of a personal voice, maybe a late-in-life fascination with superfluity,” she writes. “But here everything fundamental seems to have been in place from the start: the careful attention to design and fabrication; the caption-before-image, tail-wagging-the-dog approach to content; the willingness to let the viewer finish the sentence.”

Design time

My colleague Lisa Boone reports on a couple who turned the footprint of a small one-car garage into a space-conscious, 300-square-foot ADU. “Despite its tiny floor plan,” writes Boone, the studio’s rooms feel unified with a simple palette, warm wide oak plank flooring and a simple white kitchen.”

Essential happenings

Steven Vargas has all the latest happenings in the L.A. Goes Out newsletter, featuring a performance by Dorothée Munyaneza at REDCAT and the landscape-inflected works of Carolyn Castaño at Craft Contemporary.

Artbound has a new episode devoted to Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros and the mural that sparked a massive artistic controversy in L.A.: “America Tropical,” the 1932 work that was whitewashed shortly after it was painted for depicting a crucified Indigenous man at its center. (I wrote about the mural’s ongoing conservation in 2017.)

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art will hold a screening of the doc and a discussion with the filmmakers on Nov. 9 at 5:30 p.m.

Passages

Robert Brustein, a passionate advocate of theater who helped found the Yale Repertory Theatre and the American Repertory Theatre at Harvard, has died at 96.

Anthony Vidler, an architectural historian who helped reshape perspectives on architecture by incorporating psychoanalysis and literary theory — and served as dean of the architecture schools at Cornell and Cooper Union — is dead at 82.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Artist Ida Applebroog, whose rather unclassifiable works examined gender, authority and her own genitalia, has died at the age of 93.

Joanna Merlin, who originated the role of Tzeitel, the eldest daughter, in the Broadway musical “Fiddler on the Roof,” has died at 92. After her success on the stage, she achieved renown as a casting director.

In the news

— Why Maui burned.

— Barry Schwabsky takes on the controversy over the firing of Artforum editor David Velasco over an open letter related to the Israel/Hamas conflict.

— A 16-foot sculpture of a horse by German artist Thomas Kilpper, made in collaboration with Palestinian youth, was removed from the occupied West Bank by the Israeli military during a raid on the Jenin refugee camp.

— Italy’s new culture minister has named a right-wing journalist and author president of the Venice Biennale.

— The best Saturday read is architecture critic Oliver Wainwright dismembering Thomas Heatherwick.

— The Dallas Museum of Art lays off 20 employees as it pursues a major expansion expected to cost between $150 million and $175 million.

— Pablo Helguera on the wealth that feeds museums — and how it connects to an open-pit mine in Chile (where one of my uncles worked).

— A federal judge has sided with three A.I. companies over a copyright dispute filed by three artists.

— I’ve been catching up on Art21 and enjoyed segments on Cannupa Hanska Luger and Paul Pfeiffer (who is opening a solo show at MOCA this month).

— A wave of choreographers are turning to literature as a source of inspiration.

— M.H. Miller on the ongoing relevance of ghosts.

— Sometimes we could all use a little Issey Miyake.

And last but not least ...

Here for all the dabke.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.