Robert Frank appreciation: Why his greatness went beyond ‘The Americans’

- Share via

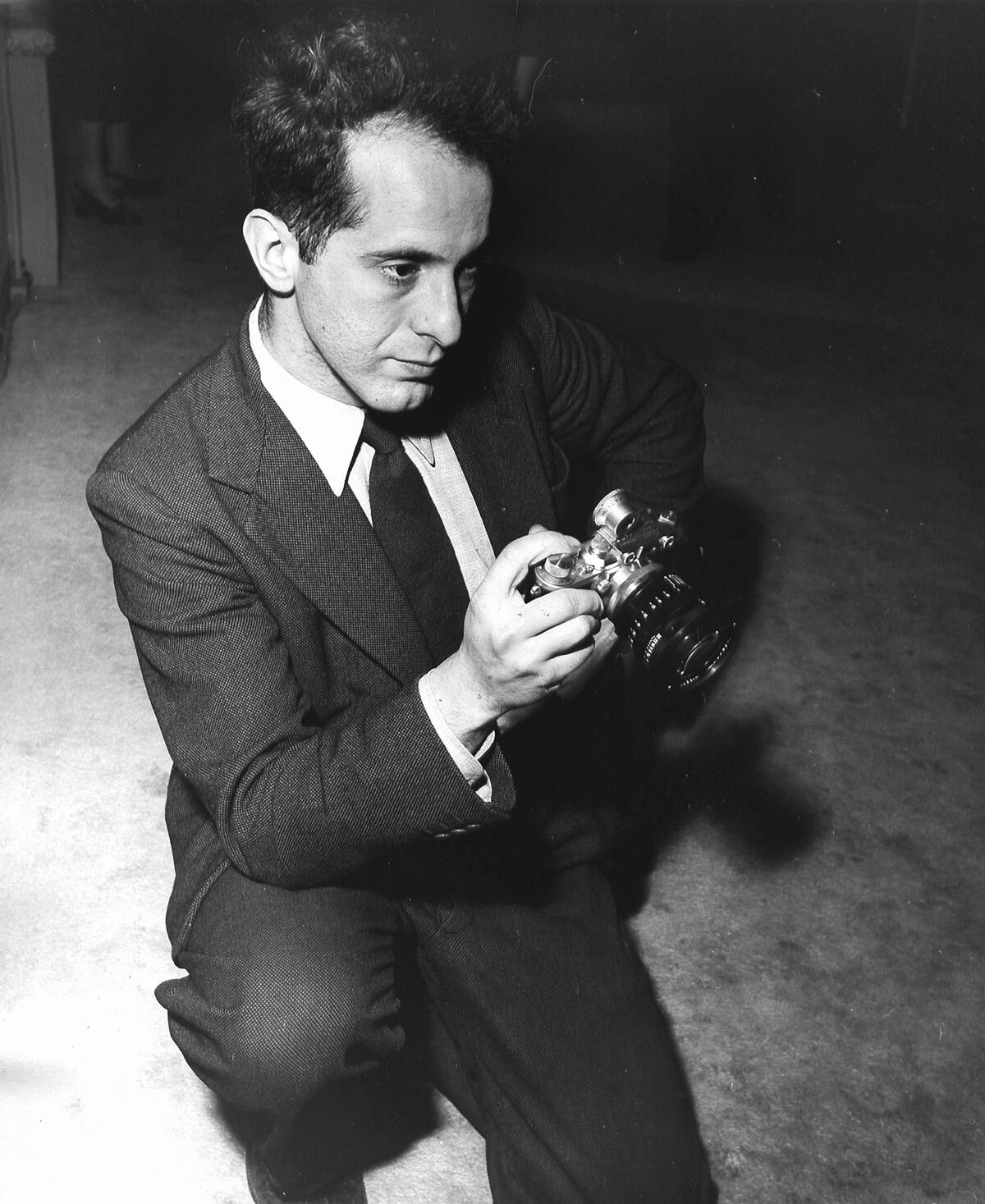

When Robert Frank arrived in Los Angeles in late 1955, he was at an emotional low point. He’d started in New York City, where he’d lived since coming to the United States at age 23 in 1947. He had chucked an award-winning stint as a fashion photographer because, in essence, it bored him.

He had been driving for weeks, and the trip had not been easy. While passing through the Arkansas taking photographs, he’d been stopped by the state police. When officers saw his New York plates and his identification showing he was born in Switzerland, they asked if he were Jewish. He was. They jailed him overnight and intimated he was a Communist spy.

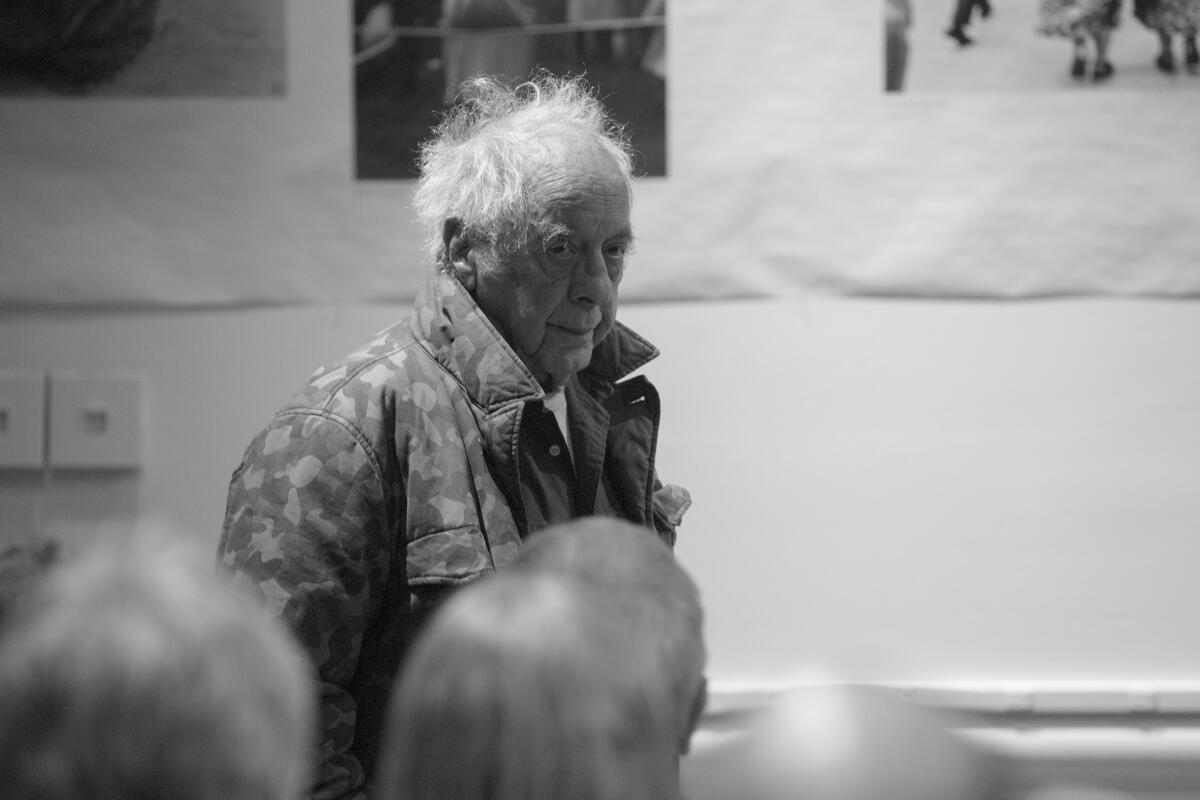

Today, we know the photographer and filmmaker as a unique American artist, a 94-year-old icon when he died in Nova Scotia on Monday. But back then, he was an unknown driving a used black Ford coupe, heading for Los Angeles after picking up his family in Texas. They stayed in a Hollywood Hills apartment. They had one car, two young children, no money and they were markedly unhappy.

“To live for two months in L.A. is like being hospitalized in a Paris hospital,” he wrote his mentor, photographer Walker Evans. “If you have to stay longer one gets worse quickly.” They were here three months.

Frank took memorable photographs of movie premieres, Bunker Hill mansions, a television studio; he photographed stock car races and the Rose Bowl. When he shot a premiere, his eye was on the fans, and the starlet they watched was out of focus. Several of his Los Angeles images ended up in the photo book that was the purpose of his cross-country drive, “The Americans.” It was published in 1959, and it changed his life.

“The Americans” gave his adopted country the respect of being taken seriously, scrutinizing race and poverty and the spaces between people without preconceptions or sentimentality. At the time, lots of folks hated these photographs; since then, the work came to be seen as the cornerstone of Frank’s career. He saw the praise coming while he was still on the road shaping the book, and he hated the fame it gave him.

Frank never wanted to repeat himself; even before “The Americans” came out, he had more or less given up still photography and turned to filmmaking, creating a whole new career. Who does that? His first movie, 1959’s “Pull My Daisy,” is a loopy Beat memoir that launched him as a serious filmmaker. For the next decade or so, he ran screaming from “The Americans,” made poetic and little-seen (for the most part) movies that also tended not to repeat themselves.

And then he arrived in Los Angeles, again. He was scraping by when an offer of commercial work came in from an unlikely source. The Rolling Stones were in town early in 1972, putting finishing touches on a masterpiece of their own, the double album “Exile on Main St.” Some of them — Charlie Watts one version goes, Keith Richards goes another — were fans of “The Americans,” and Frank was invited to the band’s Bel-Air villa. He arrived, shooting Super 8 film as he was introduced to one and all, and the older, cranky hipster with a marked Swiss German accent made an instant impression on band members. They asked him to shoot pictures for their album cover.

Frank wanted to photograph them in a Main Street flophouse, the band storming downtown in a convoy of Cadillacs, but he didn’t have the $15 to pay the hotel clerk for a room. Just then, Mick Jagger swept in, asking how many rooms were available and whipping out cash. “Rent them all,” he said. Everybody got what they wanted.

The vibes poured freely, and Jagger, who was deeply interested in movies, invited Frank to accompany the band on its North American tour that summer. The Stones gave him carte blanche to shoot what he wanted, few questions asked. The work that resulted, a notorious debauchery with a lewd title (“.....Blues”) , became a fresh sensation even before almost anybody had seen it.

The film features drug use and nakedness on private jets and TVs flying out windows. Those were the headlines, but what made it a lasting, haunting work was the understanding Frank had for the Stones’ experience of traveling across a country you were speaking to but never really seeing. The film is a document of visually beautiful, numb boredom. America was fascinated by the band’s celebrity, and the Stones were present from a great distance. “It’s really crazy,” Frank told a writer. “You go to a big effort to get everybody up for you, and then you use all the force you have to keep them away from you. It’s like being untouchable. Going through America in a Lucite spaceship.”

”.....Blues” appears sporadically on the internet in sometimes edited, vastly inferior bootlegs; few have seen the original. That’s because after viewing it, Jagger told Frank that the movie was great but that it could never be released. Footage of the drug use could affect the band’s ability to tour across national borders, lawyers said; besides, there was little music in the footage, largely because Frank didn’t care about that — he was interested in celebrity, and detachment, and America.

He wasn’t going to take out the objectionable scenes, and at one point, he hid his print under the floorboards of his Canadian summer home when the Mounties came to impound it. Eventually, Frank won the right to screen the film a few times a year if he were present to take questions from the crowd. Frank was never one to enjoy the spotlight, and it was an agreement crafted brilliantly by Jagger to all but ensure that few would ever see the film to its best advantage.

Maybe that will change now. It became perhaps the most famous, certainly the most notorious, film of Frank’s career. It lives as a masterpiece and a symbol of not backing down, not cashing in.

Around the time he met the Stones, Frank was revising his feelings about his most famous work. He wove a few images from “The Americans’” road trip into the album cover of “Exile.” Photographs from “The Americans” would show up later in exhibitions wrapped in barbed wire, stacks of now-revered pictures on display with holes drilled through. They’d show up in his films, as mementos of his past, a past he seemed alternately at peace with and ready to bury.

Frank made “The Americans” in the 1950s, and he unmade it the rest of his life. When we celebrate him today, we should think of him as somebody restless and dissatisfied with his country and himself, someone always asking questions. The work is one fine thing to celebrate. The stubbornness is another thing worth remembering this week.

Smith is an L.A.-based writer and author of “American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank (Da Capo Press, 2017). He is currently working on a biography of Chuck Berry in the age of #MeToo.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.