What director Phillip Rodriguez says now about the killing of Ruben Salazar

- Share via

In “Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle,” director Phillip Rodriguez painstakingly explores the life and death of the reporter whose public and private lives — as well as his tragic death — have inspired artists, writers, musicians, playwrights and subsequent generations of journalists.

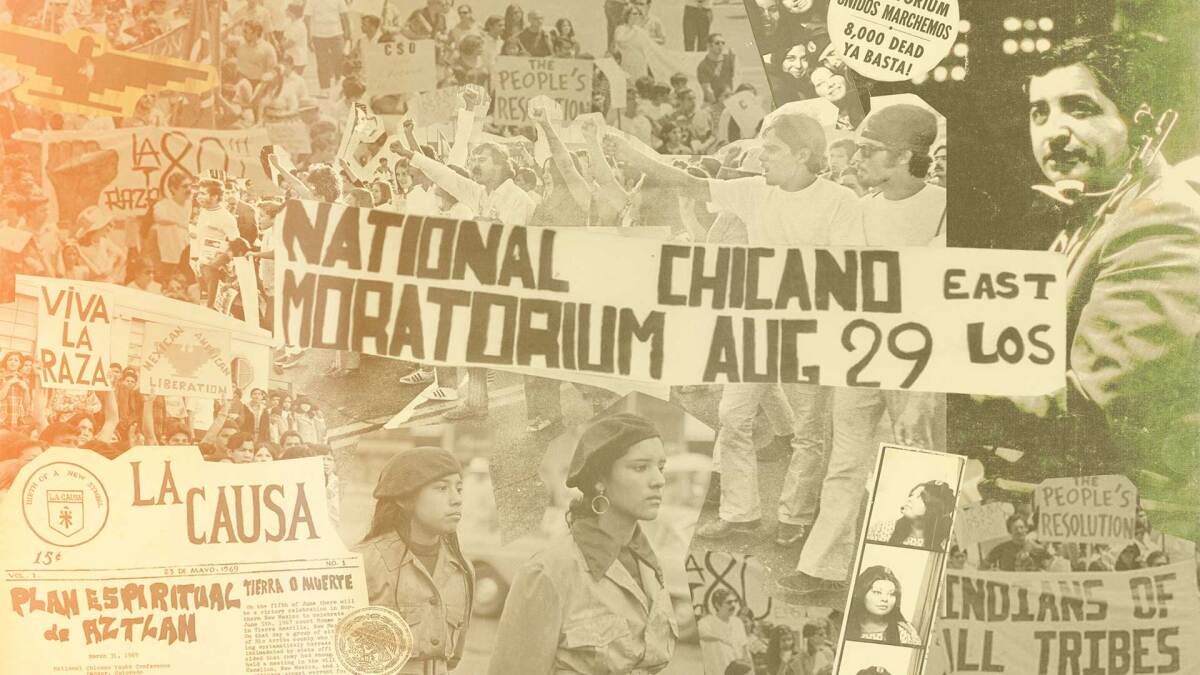

Rodriguez uses extensive archival footage in the 2014 PBS documentary, along with narrated snippets of Salazar’s rare personal writings, to reconstruct the career of a bright young reporter from Ciudad Juarez and El Paso who got his start as an investigative journalist at the El Paso Herald-Post and quickly made a mark on Los Angeles after arriving to work at The Times in 1959. Salazar did foreign tours in Vietnam and in the Dominican Republic and served as bureau chief in Mexico City before being called back to cover a brewing political phenomenon, the Chicano movement, on the streets of the Eastside.

Cutting the figure of standard newspaper journeymen of the era, with neckties and pomaded hair, Salazar found himself at social events where the white ruling class of Southern California mingled with the ethnic Mexicans who have always been there — the less-than-equal background characters, Rodriguez argues in the film, in what remains a stubbornly Anglo-centric narrative embedded in the state’s official history.

There are incredible insights throughout “Man in the Middle,” including from Salazar’s children. The film also offers a window into the prevailing mind-sets at the L.A. Times around the 1960s and ’70s — that of a conservative newspaper with little regard for Mexican and Indigenous Angelenos. “Nobody had created the term ‘diversity,’ it didn’t exist,” says William Drummond, another trailblazing Times reporter from the era, in the film. “You had to work within the system that was there, and Ruben could do that.”

Rodriguez is also known for his 2017 film “The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo,” about the life of a more rambunctious movement-era chronicler, Oscar “Zeta” Acosta, who was also a lawyer and helped document the Chicano Movement from a distinctly “excess”-addled perspective. Historical figures — including the late gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson, who transformed Acosta into Dr. Gonzo for his Rolling Stone stories — are depicted by actors who speak as though sitting for an interview.

Rodriguez himself grew up like many of the figures in the Chicano movement, middle-class and destined for college, a profile that is generational in Southern California yet largely absent from prevailing narratives that center white “natives” or immigrants. I asked him about this topic recently and about how we should understand the legacy of Ruben Salazar as the 50th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium approaches.

How did you first hear about the Chicano Moratorium?

Oh, it was simply part of the Mexican American lore. I probably learned about it from a Chicano studies course taught by Alex Saragoza at UC Berkeley.

Why didn’t you hear about it in high school? Or while growing up in L.A.?

Because I was raised in a white-flight suburb, so that really wasn’t the groove. And my parents were a little bit older. They were the Greatest Generation; they really weren’t Chicano-generation people. So it really wasn’t their jam. Not that they were entirely unsympathetic, but it wasn’t their cause.

How does your personal background inform this film? It seems that your inquiry into Salazar’s life is partly rooted in a search for self. Why did you make ‘Man in the Middle’?

My work is ... just trying to put myself together, trying to complete an idea of where I come from, what my moms and pops and aunts and uncles endured, and what the context of their lives was. Simple as that.

How would a figure like Ruben Salazar help you understand that?

Well, simply, Ruben was a middle-class Mexican American who was educated, like my parents, and who was pretty much thoroughly assimilated, who lived in a suburb, on a quiet street, in Santa Ana. I thought that that particular story, the Mexican American experience, has been under-told. I wanted to excavate what that experience was. Now, of course, his story intersects with the next generation’s phenomenon and expression, the Chicano thing. And that makes it even more interesting.

How do you see Salazar’s trajectory as a journalist? Did his final columns for the newspaper make him more of an advocate?

He was definitely explaining for the readers the phenomenon they were witnessing. You’ve got to remember, at the time there was the L.A. Free Press, La Raza magazine. He wasn’t writing for either of those. He was still writing for pretty staid media outlets. The L.A. Times reader base was white and suburban. And the KMEX audience was older, Spanish-dominant and rather conservative. So in the most mainstream environments, certainly he was explaining the phenomenon to people who were outside of it, by and large.

I found it interesting that activist Rosalio Muñoz says he was wearing a button that day.

It may well be true that he was wearing a button. And it certainly may be true that he was sympathetic, or growing in sympathy. Two things frame that possibility. First, that he was assigned to Vietnam and had witnessed the U.S. intervention in the Dominican Republic before that. It’s very possible that maybe those things radicalized him a bit. And maybe being witness to U.S. imperialism in Third World countries may have done that.

Finally in Mexico City, he sees authoritarianism turn on its people. That may have had an effect on his thinking and about his own assimilation project, and his own respectability politics project. But there’s no evidence of that, except for the articles. He did not have an active private journal that he kept during this time, during his later years.

I found his Mexico City stint so fascinating, being a former correspondent there myself. What do you think happened with Salazar and his coverage of the Tlatelolco massacre?

In my film, his old buddy makes the claim that Ruben “missed the story.” I’m not entirely sure if that’s fair. … He covered it, but I’m not sure how deeply he was able to penetrate the government sources or the phenomenon itself. And certainly, in [The Times’] letter to Ruben, calling him back home, there’s no suggestion that Ruben failed in his assignment in Mexico City. It’s simply that he was deemed to be valued. They had to figure out East L.A. and what was going on in town, and they brought him back.

As far as Mexico goes, we all know, as Mexican Americans, certainly at that period, how we might’ve been viewed by Mexican elite. We’ve all had our encounters.

Oh yeah.

Right. I’m not entirely sure what that dynamic was, to have been living in Mexico. A foreign correspondent for a major publication, such as The Times, was a position of considerable privilege. And I can imagine that maybe in his imperfect Spanish and his pocho status, with a gabacha wife, that maybe some members of the PRI [Institutional Revolutionary Party] of the Mexican government, may have been slightly bemused or hostile or unhelpful.

You also reveal in the film the fascinating status of his home life; you mention his Anglo wife and living this kind of like bifurcated life. What do you think that reflects?

It was certainly a complicated negotiation, or a renegotiation of a guy who had made a deal with whiteness and had benefited from that deal with whiteness. And now in the midst of a renegotiation of whiteness, vis-à-vis the two groups, he has to reassess. I’m sure it was complicated for Ruben.

As for his death, are we really to believe that this was fully just a freak, tragic coincidence? Or do you think there is any room for still pursuing maybe a deeper layer of truth or intent in the death of Ruben Salazar?

There’s always a possibility of that. But I looked thoroughly through the files, the photos, the L.A. Sheriff’s Department audio from that day. I listened very carefully through every moment of it. And I found nothing to lead me to believe [he was targeted by the deputy] ... I spoke with the Mexican American owner of the Silver Dollar, a gun aficionado. And he says to me, it’d be impossible on such a bright day with such a crude instrument that you had never used before to accurately shoot into a dark space, without a sight or something more sophisticated, and get that lucky. It’s not possible.

I’m comfortable with the conclusion but also quite open to any other more sensational interpretation. Now toward that end, when we sued the sheriff’s department and forced them to release their files, I made those files available to USC, where we donated them. And they sit there. Anyone who has gumption or the intention to find something different, I would suggest they do. History will always be rewritten, and God bless, that’s terrific. I wish I could have found it, but I didn’t, because I don’t think it’s there.

One of the interesting aspects of the legacy is what’s going on today at the L.A. Times with the formation of a Latino Caucus within the L.A. Times News Guild at what was once a virulently anti-union newspaper. How would you frame Salazar’s legacy now?

When Ruben Salazar was doing his thing, Mexican Americans comprised roughly 13% of the population of this place. Now that [Latinos] are nearly 50%, or thereabouts, it seems to me that the fact that we’re still having conversations about inclusion and diversity and representation in newsrooms, from a place like the L.A. Times, is an indictment of something and someone.

Oscar “Zeta” Acosta, a contemporary of Hunter S. Thompson and the subject of “The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo,” was writing about the same thing as Salazar — this Eastside movement. How are their stories similar or divergent?

They had some kind of reporter-activist-journalist relationship, which Acosta writes about. He calls him Zanzibar, and there is a story of a [TV] interview Salazar did with Acosta. But KMEX erased all their tapes, so there’s no record of it. Immediately after Salazar’s death, Acosta really reared his hind legs, insisting that there be a proper investigation.

He was part of the blue ribbon commission [formed to investigate the Salazar death]. He was very verbal and he was very physical. He went to the scene of the crime, spoke to many people in the community, insisting that they testify to him and then be allowed to testify at the inquest. But, yes, one was playing it straight and one wasn’t. One was middle-of-the-road and middle-class, and one was intoxicated with the counterculture.

Acosta died, or is presumed to have died, in 1974, in Mexico. His remains were never found.

Both of them didn’t go out pretty: mysterious circumstances, you can certainly say that. And Acosta’s death was likely violent as well. Easy to chalk it up as the death of a loon, of an extreme personality, but with Salazar, that argument is impossible to make because he was as sober as a judge.

How should that generation be historicized today, given that L.A. is, for example, significantly more Central American now, and Asian, and of course Black — and that conversations and political currents have sort of turned away from the ethno-nationalism and the machismo of that era?

Well, first of all, I object to the conflation of the use of “machismo” with ethno-nationalism. I mean, my father used to say macho was the only word that gringos know that’s in Spanish.

So as for the answer ... I don’t know. I mean, they certainly have a place, an important place in the cultural and political history of this city. And I don’t think that the arrival of new Latin American exiles from other places in any way contradicts or takes anything away from that. I was hoping that we can fuse these experiences — and that the young girl from Guatemala, a child, can somehow make Gloria Molina’s examples her own as she moves into a position of influence in her own life. So I don’t see a contradiction. I think Mesoamericans are pretty much the same people, divided by imaginary boundaries. That’s my take.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.