Once upon a time, a theatrical ‘Dream’ came true at the Hollywood Bowl

- Share via

The muses of theater, dance and music occupy a Moderne fountain at the Hollywood Bowl’s North Highland Avenue entrance. The sculpture reflects the venue’s founding vision, which lacked a clear preference for one art over the others, even if music (being most at home at the outdoor amphitheater) was naturally given pride of place.

Yet it was a theatrical offering — one of the most ambitious artistic undertakings in the history of Los Angeles — that elevated the Bowl’s stature in the eyes of the world.

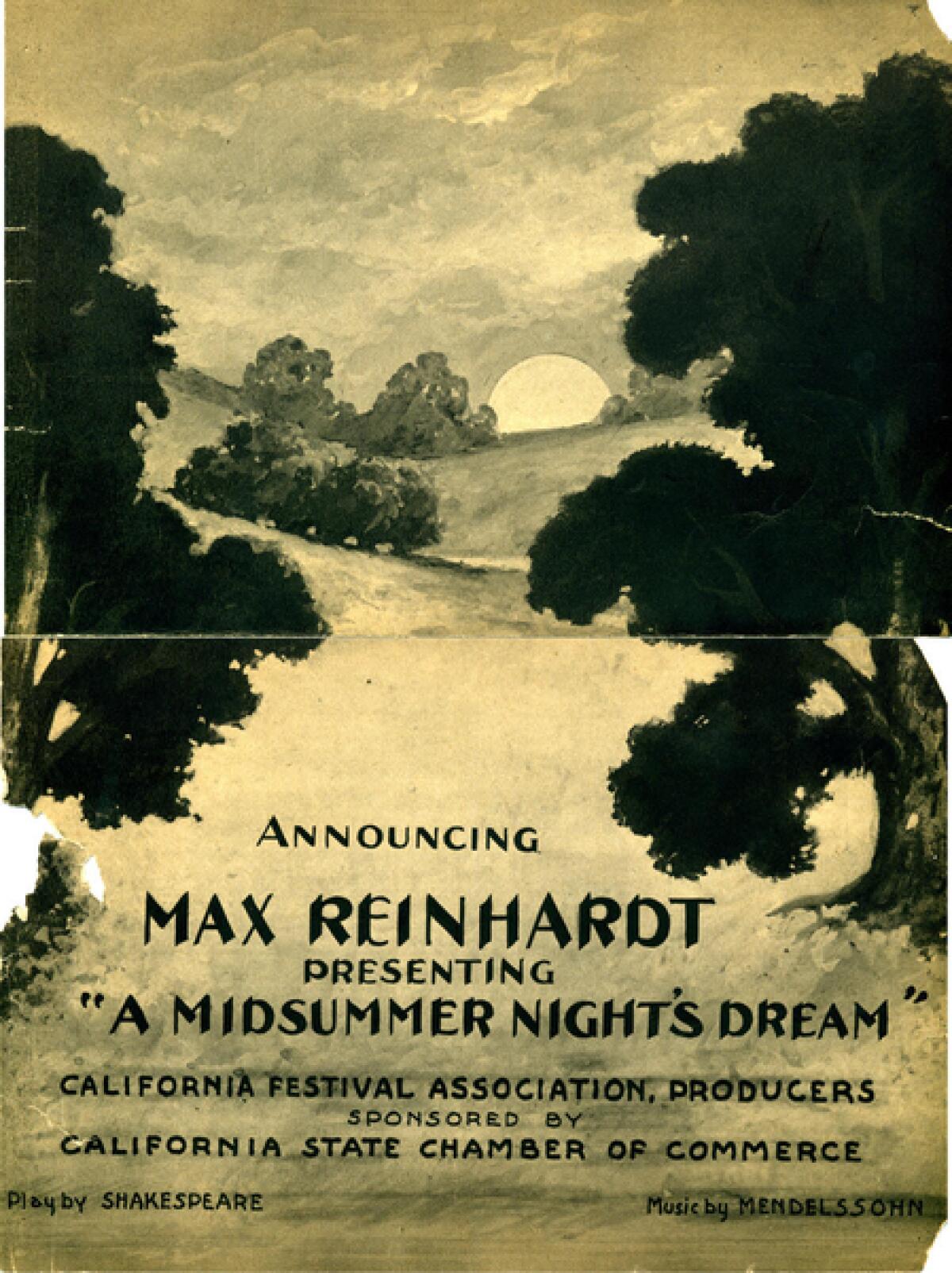

In 1934, Max Reinhardt, the eminent Austrian-born director who was one of the founders of the prestigious Salzburg Festival, was invited to present William Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” in an extravaganza that took full advantage of Los Angeles’ natural and cultural resources. Operating on the scale of a small military operation, the production featured an ensemble of more than 400 artists, including 18 principals, 60 or so dancers and several hundred extras.

The Bowl was reconfigured for the occasion. The band shell was dismantled and put in storage. A gigantic stage was built and covered with green sod, heavy foliage and oak trees shipped in from Calabasas.

The play’s fairies crossed a suspension bridge that was erected to make it appear as though they were frolicking in from the Hollywood Hills. A hillside twinkling with fireflies required 30,000 electric lights and a special transformer to carry the additional load of electricity.

Music and dance were interwoven in a festival production that approached Wagner’s idea of the integrated artwork, or Gesamtkunstwerk. The Los Angeles Philharmonic orchestra, under the direction of Reinhardt’s longtime music director, Einar Nilson, performed the overture and incidental music Felix Mendelssohn composed for the play. Theodore Kosloff was ballet master; dancer Nini Theilade and a ballet corps of fairies were commended by the New York Times for their exquisite grace.

The vision, following the model set by Shakespeare and the ancient Greeks, was to bring all strata of society together — groundlings, swells and everyone in between. The production had an international imprimatur, but much of it was locally sourced.

Civically inspired, Hollywood made itself readily available, ensuring maximum publicity. Academy Award-winning art director and designer Max Rée was brought on board for the costumes. Felix Weissberger, Reinhardt’s trusted assistant director, announced, “We expect to draw from the motion picture colony for our cast,” and made good on the promise.

The ensemble included 14-year-old Mickey Rooney as Puck (in a rascally role he was born to play, even if he hadn’t read a word of Shakespeare until then) and a young starlet destined for fame named Olivia de Havilland, who played Hermia. They would reprise their roles in the 1935 film that Warner Bros. was inspired to produce after Reinhardt’s tremendous success at the Hollywood Bowl.

It’s impossible to overstate the impact of this theatrical event. The production, which played the Greek Theatre in Berkeley after its Los Angeles run, was underwritten by a group of Californians “looking toward the establishment of California’s leadership in America’s cultural endeavors,” as a Times reporter characterized it.

Principally at stake was Los Angeles’ cultural standing. William May Garland, leader of the California Chamber of Commerce, expressed the hope that Reinhardt might be persuaded to return annually to make the city “the Salzburg of the Pacific Coast.”

“It is the most important production from the standpoint of dramatic value ever staged in California,” The Times declared on the eve of the opening. “It gives Los Angeles a distinction enjoyed similarly by such centers of art and culture as Florence, Vienna, Berlin, Salzburg and Oxford.”

The New York Times grumbled with typical East Coast condescension that too much time was taken at the opening night gala to announce the arrival of Mae West, Marlene Dietrich and other luminaries who had the spectators agog before the play even began. But nothing could upstage this spectacular, which was seen by more than 100,000 people during its eight performances at the Bowl.

In his eloquent review for The Times, Edwin Schallert confirmed that history was made:

“The poetic word, pageantry, music and spectacle are all mingled to create a spell that is unearthly, and that has the true quality of fairyland. From the first glimpse of gleaming torches literally dancing on a hillside to the final procession of fire marching virtually down a mountain one is some place beyond all actual mundane confines, watching a bewitching processional of romance and of comedy, conjured by a master hand and by an intuition remarkable.”

If only the ambition behind this “Dream” had become an annual rite. But theatrical productions have rarely, in my experience, been the centerpiece of the Bowl’s summer seasons. Too often the formula revolves around casting big names from TV and film in musical warhorses.

But occasionally, the planets align and something miraculous occurs. As it did in Robert Longbottom’s 2019 production of Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s musical “Into the Woods,” which coincidentally also follows a group of rowdy, mixed-up characters into a supernatural bower.

The grande dame of amphitheaters, which celebrates its centennial this year, defines L.A. life as only Angelenos can understand.

The main stars that weekend were in the heavens. Not that there weren’t theatrical luminaries of the first rank. The company included Sutton Foster, Sierra Boggess and Patina Miller, but these talented troupers shined brightest as an ensemble.

The lesson of Reinhardt’s production still holds: Hire an expert director who isn’t afraid to dream big or let the Bowl’s open-air enchantment intermittently steal the show.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.