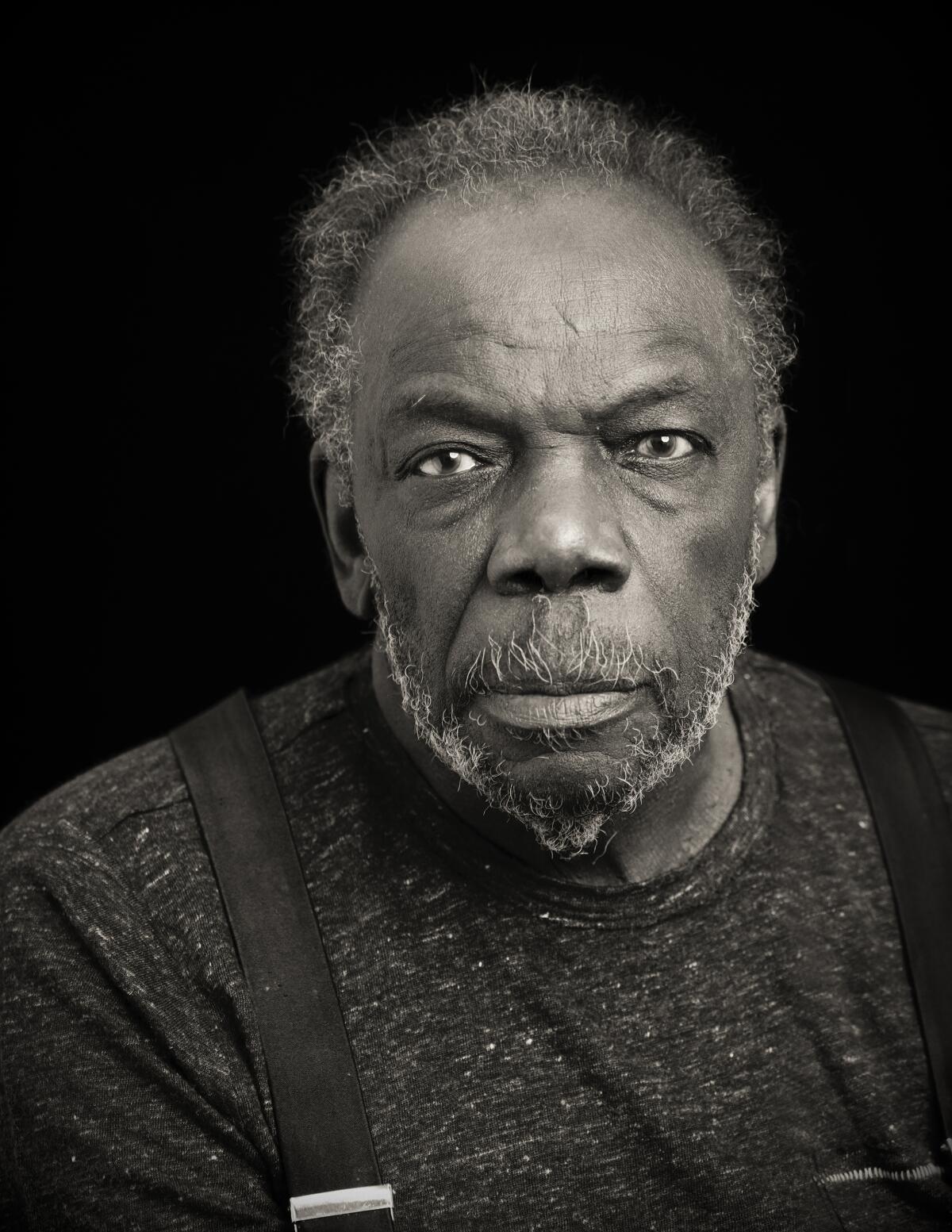

Why the late Sam Gilliam’s inventive abstract drapes celebrated artistic difference

- Share via

Sam Gilliam, an artist who fused painting with sculpture in vividly colored canvases that he removed from their wooden stretchers and suspended in space, died of renal failure on June 25 in Washington, D.C., where he lived and worked for six decades. He was 88.

The work for which he is best known, typically referred to as “drapes,” were at the leading edge of abstract art when he began them in 1967. Accentuating the material properties of paint, he used mops, rakes, brushes and simple gravity to apply vivid color to canvases that hung in space from the ceiling or gathered in bunches from pegs, rather than hanging stretched and flat against the wall. Establishment ideas of advanced art lionized abstraction for emphasizing the distinct formal qualities unique to paintings and to sculptures. Gilliam, however, along with such diverse artists as Jay DeFeo in San Francisco, Eva Hesse in New York and others, crossed those separate circuits. Painting merged with sculpture in lush chromatic fields.

A local schoolteacher, he had been included in a few modest group shows before then, including “The Negro in American Art” at UCLA in 1966 and the inaugural presentation two years later at the Studio Museum in Harlem. But Gilliam erupted onto the national art scene in 1969 with his eye-opening participation in a three-artist exhibition at Washington’s Corcoran Gallery of Art, a museum now closed. He suspended huge, brightly painted drapes from skylights at the top of the four-story atrium of the 1897 beaux-arts building.

The colorful swags stood in stark contrast to the elegantly traditional space, which stood across the street from the White House. Many Black artists at the time made paintings and sculptures in figurative modes that represented social and political themes. At the height of the civil rights movement in the nation’s capital, Gilliam’s inventive abstract gesture celebrating artistic difference was immediately embraced.

Born in Tupelo, Miss., the seventh of eight children of a seamstress and a carpenter, Gilliam received his bachelor of arts and master of arts from the University of Louisville in Kentucky. Over the years, he was awarded honorary doctorates from seven art schools, including his alma mater. His work is in the collections of the National Gallery of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego and other museums internationally.

Following the Corcoran exhibition, Gilliam showed widely over the next half-century, but his work rarely appeared in Los Angeles. He was nearing 80 when his first solo gallery exhibition opened here in 2013 at the David Kordansky Gallery, where he showed three times since.

Gilliam’s marriage to Washington Post reporter Dorothy Butler ended in divorce. He is survived by his wife, Washington art dealer Annie Gawlak, three daughters from his first marriage and three siblings.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.