A smart yet narrow ICA L.A. show confronts marginalized people’s visibility and invisibility

- Share via

As luck would have it, social media was filling up with a relevant smackdown on the day I went to see the new exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. During a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing the day before about the impact of the Supreme Court’s decision to reverse Roe vs. Wade, the landmark case that provided a constitutional right to abortion, Khiara Bridges, a law professor at UC Berkeley, schooled Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) on unexpected consequences of the ruling.

Hawley, who gave a clenched fist salute to the male white supremacist traitors who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, oozed superciliousness as Bridges coolly explained how serious harm, including physical violence, is done through the refusal to acknowledge that transgender and nonbinary people even exist, since both can indeed become pregnant. The sickening impact of reversing Roe doesn’t only fall on women. In the academic clarity of her explanations, she could have been writing wall labels for “The Condition of Being Addressable,” the ICA L.A.’s current show.

The exhibition considers a proliferation of art concerned with the marginalized state of being socially and culturally invisible or, conversely, hyper-visible. Work by queer artists, women and artists of color is on view. Twenty-five artists from multiple generations have been assembled by Marcelle Joseph, an independent curator based in London, and Legacy Russell, executive director at the Kitchen, an experimental interdisciplinary art space in New York. They worked with ICA L.A. curatorial assistant Caroline Ellen Liou.

Paintings, photographs, sculptures, installations and videos are included, with one and sometimes two pieces per artist featured. Things kick off in the parking lot with a brightly colored, four-panel wall mural by Argentine artist Ad Minoliti, its flat but snappy mix of suggestive geometric and organic shapes said to describe an “Aquelarre no binario / Non-binary coven.” Loose suggestions of interlocking limbs, heads and other human or animal body parts dart in and out of view among graphic signs, so you can’t be quite certain what you are seeing.

The same goes for a video by Sin Wai Kin, albeit in a very different way. Displayed as a conventional odalisque — a reclining nude — in an unexpectedly static five-minute video shot. The artist, who identifies as nonbinary, pushes gender performance to an extreme with outlandish makeup, an enormous cascading wig, mesh stockings and prosthetic breasts. Once you know that Sin is a drag queen born female, the usual drag exaggerations of hair, eyes, lips, legs and bust that traditionally satirize the erotic focal points that attract the gaze of heterosexual men get destabilized. Just who is being addressed here?

Nearby, a classic 1975 digital print by Lynn Hershman Leeson provides some social and cultural backstory to Sin’s free-floating personal fiction from 2018. Hershman Leeson’s self-portrait diagrams the makeup required to transform the artist into “Roberta Breitmore,” a fictional persona she invented and fully inhabited from 1973 to 1978. Even that chosen moniker, Roberta Breitmore, sheds “more light” on “Roberta,” a feminized male name, upending assumptions around confident self-portraiture.

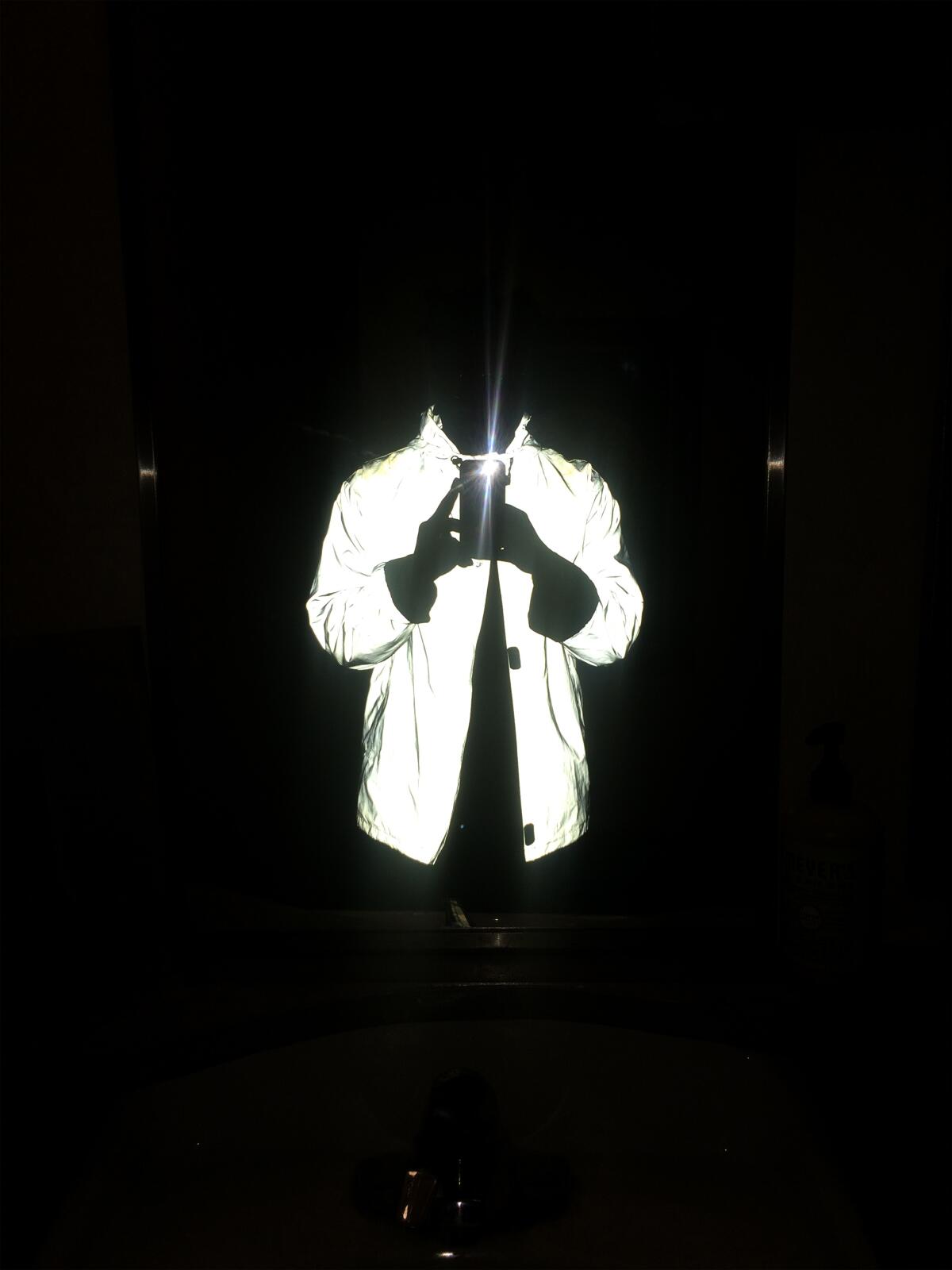

Some of the show’s more modest works are among the most compelling. Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s photograph, a pitch-black nighttime selfie of the Black artist, makes her essentially invisible, save for the glowing white jacket she wears. Silhouetted, she’s holding up her cellphone camera, its bursting flash aimed directly at the viewer. Because McClodden’s photograph is under glass, your reflection encompasses her body — a provocatively concise digital inquiry into the nature of social and cultural representation today.

High up in the corner of one gallery, a small plastic dome with a blinking red light implies the typical surveillance cameras that keep an eye on the comings and goings of art museum and gallery visitors. (Don’t touch!) Aria Dean, however, has pulled a subtle switch: This is a “Dummy Cam (icon),” not an actual camera, and all it does is idly blink.

At least, I think that’s all it does. Should we trust the information on the wall label, since surveillance-equipped museums don’t seem to trust us? The tables get turned, as we are now surveilling it. Which also makes one wonder: For security purposes, isn’t that enough?

Is the mere threat of being watched an adequate security intimidation by “them” against “us”? Dean’s sculpture put me in mind of a “blp,” those wonderfully weird, often fuzzy little black wall sculptures, shaped like a lozenge, that the late Richard Artschwager would insert here and there in his exhibitions, the better to confuse the otherwise routine event by drawing visitors to consider the real-world context outside his more conventional art objects in the show. Think of Dean’s little sculpture as a poke in today’s ubiquitous electronic eye.

“Dummy Cam (icon)” is lodged up in a corner between a characteristic work by an established artist, Lorna Simpson, and a recent piece by Troy Montes Michie, a younger, less recognized one. The juxtaposition suggests historical continuities.

A high-style zoot suit, chopped up and reassembled as a textile collage by Michie, is titled “Tacuche #3,” a Mexican colloquialism for “suit” that also means “rags.” A pair of black dress shoes with glitter insoles tucked inside is suspended from the tacuche hanger. Enflamed with the history of violence toward Mexican Americans embodied in the zoot suit, the sense of slippage — between elegance and trash, peace and pugnacity, polish and vulgarity, straight and queer — resonates with Lorna Simpson’s sequence of photographs and texts. Six fragmentary, cropped pictures of a Black man posed almost as if in a modeling shoot are underlined by seven text captions — too many for a one-to-one connection between words and images. Identity becomes a performance of shifting perceptions between the seer and the seen.

Simpson’s “Gestures/Reenactments” was made in 1985, the year Michie was born. The show makes savvy intergenerational points with work by a number of women and BIPOC artists who emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, including Hershman Leeson and Ana Mendieta, the latter represented here by photo-documentation of her clipping a man’s scruffy beard and painstakingly attaching his facial hair to her own chin.

One drawback, though, is a general New York/London curatorial tilt in the overall selection. It feels rather narrow, if still smartly chosen.

For instance, Mary Kelly’s use of compressed laundry lint, an unusual art material, to create small text panels is, as the accompanying wall label says, a “fleeting reminder of the never-ending rhythms of women’s domestic labor” — just as it was for the missing art of Slater Barron, dubbed the Lint Lady of Long Beach in the 1970s. The marvelous painted cutout of a watchful Harriet Tubman, fearless abolitionist and social activist, by British artist Lubaina Himid would be interesting to see with the similarly theatrical painted cutouts of Florence Nightingale, Tubman’s contemporary, made in 1977 by San Diego-based feminist artist Eleanor Antin, also absent. For an L.A. exhibition, the inclusion of artists such as Barron and Antin would have made special sense.

The most mesmerizing work is Sondra Perry’s sculpture, an eccentric office workstation cobbled together from an exercise bicycle and a wraparound trio of flat-screen monitors. One reason it’s captivating is that, unlike several other video works that require the clumsy use of headphones so as not to disturb fellow visitors, the conveyance of sound is integral to Perry’s sculpture.

Don the exercise bike’s conventional headphones, and a hypnotic, AI-manufactured figure floating across the screen leads you through a maze of questions peppered with pointed observations. They start with an inquiry into what social conditions enabled you to even be in an art gallery, of all places, in the middle of the day. Challenged to explain yourself to yourself, you readily want to know more — the start of a clever workout in more ways than one.

A 25-year survey of the L.A. artist speaks to our conflicted moment.

'The Condition of Being Addressable'

Where: ICA L.A., 1717 E. 7th St., Los Angeles

When: Wednesdays through Sundays, noon-5 p.m. Closed Mondays and Tuesdays. Through Sept. 4

Contact: (213) 928-0833, theicala.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.