- Share via

- Guadalupe Rosales, 45, delivers a vibrant exhibition that looks into 1990s images and experiences through a Chicana lens.

- The title of the show centers on a Nahuatl word for spiderweb, a common metaphor for fragility, interconnectedness, beauty and, not least, potential entrapment.

- One surprising element: engrossing display cases with zines and memorabilia of daily life during the fraught era of Rodney King and the AIDS epidemic.

As an artist, Guadalupe Rosales is having fun, and she wants her audience to have fun too — and to think about what fun is and means. At least that sentiment, oriented toward pleasure and freedom, is what’s telegraphed in the center of the Los Angeles-based artist’s engaging and very timely solo exhibition at the Palm Springs Art Museum, where a checkerboard dance floor fills the central space.

A makeshift DJ booth, assembled from a couple of upended shopping carts and some speakers, is at one edge of the checkerboard in the dimly lighted room, underscoring the general do-it-yourself ethos of Rosales’ aesthetic. Motorized blue spotlights skitter across the floor and climb walls to the ceiling, where they rush past a pair of mirrored disco fixtures.

These are not conventional “Saturday Night Fever” spherical mirror balls but small rotating step-pyramids, doubled-up, flat sides pressed together one atop the other and then suspended, like mirror reflections of themselves. Teotihuacán meets Café Tacvba, a playful merger of ancient Mesoamerican civilization and a 1990s rock en español band in suitably fractured light.

The ’90s is the decade when Rosales, 45, entered her teenage years growing up on Los Angeles’ Eastside. Like Teotihuacán and Café Tacvba, her exhibition looks into formative images and experiences from the past, glimpsed through a Chicana lens. (Women are prominent in the imagery.) She’s gathered up ephemera — magazines, snapshots, lowrider bicycle parts, bandannas, street signs, keychains, newspapers, fuzzy dice to hang from a car’s rearview mirror, feathers, fake flowers and more — and she’s put them to one of two primary uses: Some form component parts of assemblage sculptures, while others are displayed in cases, like rare anthropological artifacts, or else tacked onto poster boards, like treasures from a teenager’s bedroom.

A side wall near the dance floor is papered with big blow-ups of joyful photographs showing jam-packed dancing at Arena, the massive, 22,000-square-foot former nightclub in Hollywood’s old Union Ice building on Santa Monica Boulevard. Arena, like the adjacent club called Circus, was established by a couple of gay and Latino entrepreneurs as open-to-everyone party spaces — a radical departure during an era when discos were defined more by the vulgar discrimination of velvet ropes and vain bouncers policing entry.

For people like me, who remember those clubs’ heyday, even a memory of the name “Union Ice” once prominently painted on the building’s street wall flips into bitter irony, now that “union” in daily American life has been purposefully shredded and “ice” has become a thuggish term representing politicized, Gestapo-like cruelty. At an art museum, a dance club’s once forward-leaning experience of scrappy social optimism — life and liberty fueling the pursuit of happiness — is enshrined as a necessary and valiant cultural value, which lends richness to Rosales’ otherwise simple materials.

The exhibition has four loosely thematic sections. In addition to the dance room, there’s an introductory entryway, a gloomy nighttime space and a car culture gallery.

The entry frames motifs that will ricochet through the exhibition, which is titled “Tzahualli: Mi memoria en tu reflejo” (My memory in your reflection). Tzahualli is a Nahuatl word for spiderweb, a common metaphor for fragility, interconnectedness, beauty and, not least, potential entrapment. Rosales juxtaposes a wall of psychedelic party posters, glowing beneath blacklight, with a roadside shrine of flowers and votive candles remembering loss. They are laid at the base of a black wrought iron gate, which doubles as a portal between public and private realms and the inescapable suggestion of prison bars.

A foundation announced the groundbreaking for the Joshua Tree Art Museum, but public records reveal a more complicated picture.

Bandannas tied and knotted around the gate put a familiar symbol of individual liberation and civil rights resistance at the heart of the work. Behind it, a wide rectangular hole cut into a hot-pink wall offers a telling peek into the inner dance room.

An eccentric fainting couch, the horizontal hole is lavishly embellished with plush pink tufted upholstery, like the tuck-and-roll interior of a sexy 1964 Chevy Impala, the ultimate “Lowrider” in the movie of the same name. That upgraded car, jacked with hydraulics, could also dance, which may explain the little mirrored disco ball dangling within the narrow void of Rosales’ sculpture.

In a rear gallery, dark nighttime photographs are hung on walls painted black to denote the wee hours. They show fragmentary urban scenes — a few palm trees illuminated by the glow of an unseen automobile’s headlights, the artist’s bland backyard, some mute shops — but the images aren’t compelling. A wall text speaks of the melancholy of returning home after a night of fun, but visually the mood is not there. Surely, they have personal meaning for Rosales’ late-night excursions as an exploring kid, but for a viewer the shadowy imagery is merely obscure.

More disarming is the car culture room, where high art and lowrider productively collide. A couple of big, brightly colored photographs of painted car hoods merge automotive details of swooping and jagged shapes with the look of abstract hard-edge canvases, a painting term coined by California art critic Jules Langsner in 1959 — the dawn of a distinctly L.A. aesthetic. Nearby, an eye-grabbing projection of “found video” snatched from the internet documents a gasp-inducing, acrobatic quebradita dance contest held in a neighborhood parking lot. (It seems to be a church event.) The amateur video, like the recreational athletic dancing shown, celebrates a kind of homemade street art.

The clip is DIY culture at its most satisfyingly vivid. By now, the spiderweb invoked as the show’s title is pretty much in focus, with very different pieces in very different rooms nonetheless intertwined with one another.

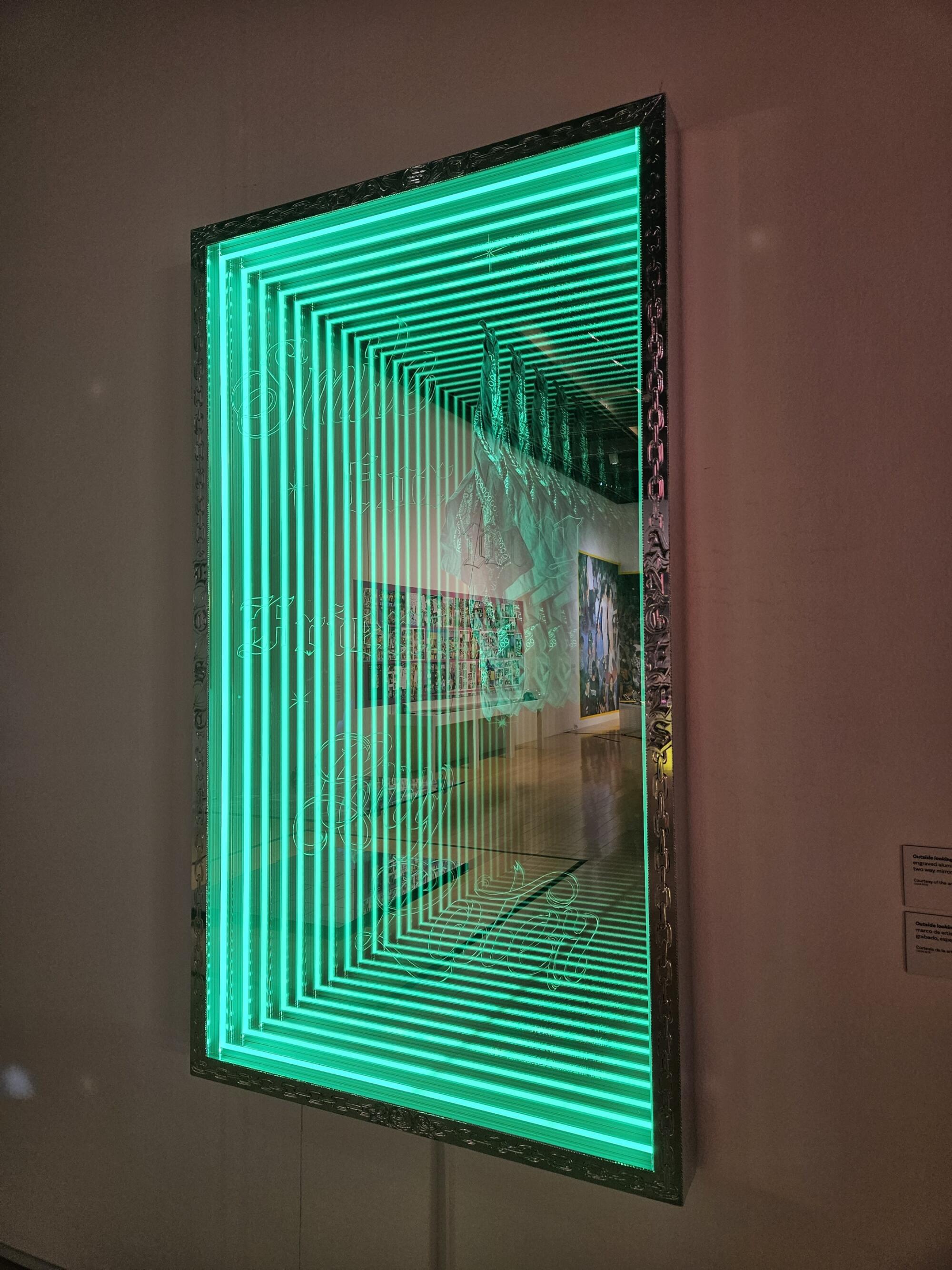

The exhibition’s strongest individual objects are three mesmerizing “infinity portals,” two on the wall and one on the floor. Rosales edged double-sided mirror glass with strips of shifting LEDs, which create a reflected illusion of depth cascading into visual eternity. One is framed in aluminum engraved with chain links and the words “Lost Angeles” written in an elaborate font that zips between establishment Olde English “Canterbury” style and illicit urban graffiti. Look closely, and “Smile now, cry later” is etched into the clear glass below a suspended bandanna, an allusion to a song by Sunny and the Sunliners, the 1960s Chicano R&B group.

For the record:

9:51 a.m. June 6, 2025An earlier version of this article erroneously said words etched in the artwork “Outside Looking In” were lyrics from a song by Sunny and the Sunliners. The etched words are an allusion to the song.

The other two portals ruminate on the 1992 Los Angeles riots in the wake of the horrendous Rodney King police brutality verdicts, as well as furious demands for gay rights and survival help as the AIDS epidemic rampaged. One surprising element of the show is several engrossing display cases with zines and memorabilia of daily life during those fraught days. An archive of throwaways gets new life when presented as a natural history composed of cultural artifacts.

As states consider loosening laws that regulate child labor, Lewis W. Hine’s early 20th century photographs, which helped child labor laws get passed, are worth our attention once again.

Absorbing works built from archives are becoming increasingly prominent in the art world. The motif is built on such diverse precedents as Fred Wilson’s sharply researched interventions into the establishment framework of museum storerooms and Elliott Hundley’s dizzying collages of material pinned with long needles to panels, which position life’s scraps somewhere between exotic butterflies captured for close study and therapeutic visual acupuncture. (An excellent Hundley solo survey is currently at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.) With this exhibition, Rosales is poised to join their ranks.

Archival interests among artists may be residue of our tumultuously evolving digital age. As they say, nothing digital is ever permanently deleted, leaving everything open to revival and reassessment. That, too, dates to the 1990s, when personal computers became common household items, putting an infinity portal into almost every home.

Think of “Tzahualli” as a worldwide spiderweb. The show was organized by PSAM chief curator and interim director Christine Vendredi, her first exhibition since joining the museum staff last year, and co-curated by Luisa Heredia. Disappointingly, there is no catalog, but fragments of the art’s fun-drenched analog Wayback Machine are destined to live on in digital ether.

'Guadalupe Rosales | Tzahualli: Mi memoria en tu reflejo'

Where: Palm Springs Art Museum, 101 N. Museum Drive

When: Thursdays-Sundays, through Aug. 31

Admission: $12-$20; children 17 and younger are free

Info: (760) 322-4800, psmuseum.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.