Appreciation: Jonathan Miller, like Carl Sagan and Anthony Bourdain, was one of TV’s best ‘presenters’

- Share via

Jonathan Miller, who died Wednesday at the age of 85, was, in no particular order, a writer, a wit, a television personality, a physician, a sketch actor, and a director of plays and operas. Many who won’t have otherwise encountered his work or person may have seen him represented, though not named, in the Season 2 finale of “The Crown,” when Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, played by Anton Lesser, attends a performance of “Beyond the Fringe” — also not named — the seminal sketch revue that launched what is generally referred to as the British satire boom of the early 1960s.

Alongside Miller, its four-man cast included Alan Bennett (later a playwright and screenwriter, whose works include “The Madness of King George” and the Tony-winning “The History Boys”) and the future team of Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. (Moore, arguably the most famous of them all, was later the star of “10,” “Arthur” and “Arthur 2: On the Rocks.”) It is a fact that Macmillan saw the show, in which Cook performed an imitation of the prime minister — the first time a living politician had been imitated in England, crossing and erasing a line in British humor — and also that, on this particular evening, Cook, aware of Macmillan’s presence, ad-libbed some new lines at his expense.

For three seasons, Netflix’s “The Crown” has inspired viewers to research the royal family and British history. Wikipedia and Google data bear that out.

Headed for a career in medicine before early success sucked him into the arts, Miller was known in America mainly from television. His documentary series, imported to PBS from the U.K., included “The Body in Question” (1978), “Madness” (1991) and “A Brief History of Disbelief” (2004, though not shown in the U.S. until 2007), in which he examined “the growing conviction that God does not exist.” (It was his take on the matter as well.) I’m not sure whether his 1983 “States of Mind,” a series of conversations with “psychological investigators” reflecting Miller’s specific interest in neuropsychology, ever aired here, but I wore out the companion print volume.

As a fan of British comedy from a young age, I knew that Cook and Moore had come out of “Beyond the Fringe” and that Monty Python owed them a debt, and I was interested in anything Miller put his hand to. There was a 1980 “The Taming of the Shrew” that cleverly cast Python’s John Cleese in the role of Petruchio, and a 1986 staging of “The Mikado,” with Python Eric Idle as Ko-Ko, set in a hotel in the 1920s. (Moore played the role when the production reached Los Angeles in 1988.) Most remarkable is a 1966 television film of “Alice in Wonderland,” described by Miller as “a long, hot, summer dream.” Filmed in black and white in country places and an abandoned Victorian hospital, made without makeup, masks or special effects, it is to my eye the best and most beautiful “Alice” — specific at once to the time in which it’s set and the time in which it was made, while feeling dazedly timeless. Ravi Shankar wrote the score; the cast includes Peter Sellers, Michael Redgrave, Leo McKern, John Gielgud and “Fringe”-mates Cook and Bennett. (“Once you take the animal heads off,” Miller said, “you begin to see what it’s all about. A small child, surrounded by hurrying, worried people, thinking, ‘Is that what being grown up is like?’ ”) His frizz-haired, 13-year-old star, Anne-Marie Mallik, acted neither before nor again.

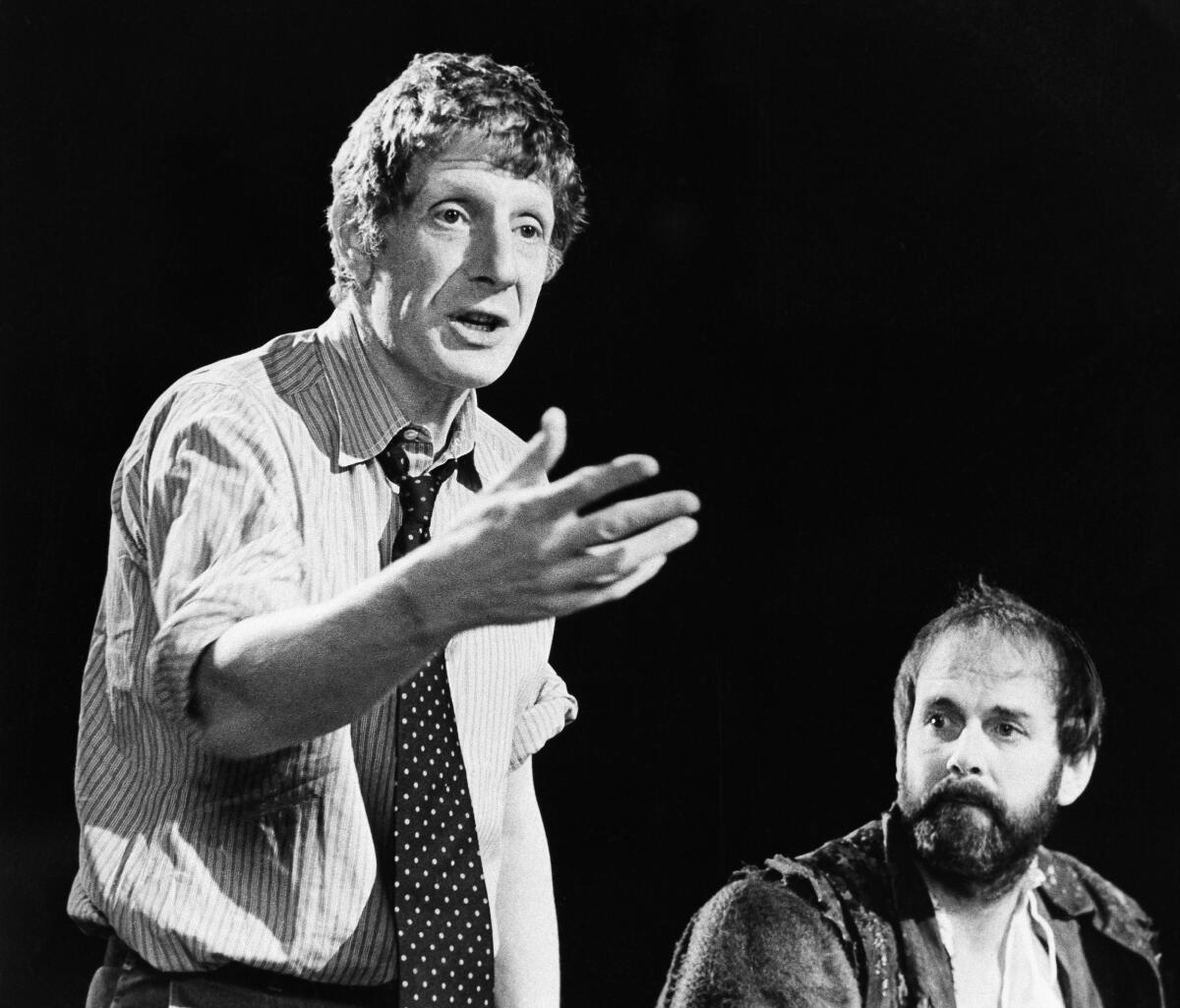

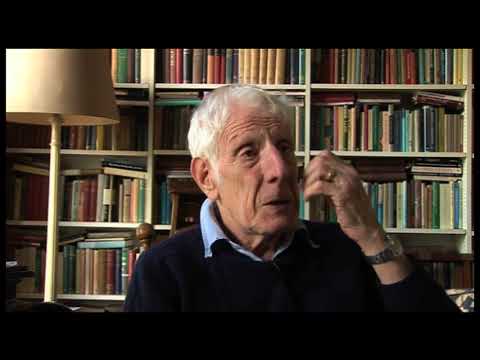

Six-foot-four in his prime, rag-doll floppy in his gestures, Miller was very much a creature in space — pushing out into it, slouched low in a seat, long legs out, elbows akimbo with hands clasped behind his head (the attitude adopted by his “Crown” stand-in), or folded in on himself, legs crossed, chin resting on a hand, as if to support all the thoughts in his great head as he sat across from an interviewer. Though many times more a presence on British television, he was no stranger to American talk shows, waxing smart or silly, erudite or fanciful across from the likes of Dick Cavett, David Letterman and Charlie Rose.

In his own programs, Miller was a presenter — not exactly what we would call a host, in the sense of a person who introduces a program and then largely disappears from it, but an informed person whose ideas we’re asked to consider and whose adventures we’re invited to share. He was an audiovisual essayist, the author and the “star,” as it were, of his series. It’s an approach made familiar here by “Alistair Cooke’s America: A Personal History of the United States,” “Civilization: A Personal View by Kenneth Clark,” Robert Hughes’ “The Shock of the New,” any number of nature documentaries from David Attenborough, science documentaries from Brian Cox, or Michael Palin’s world-circling travel shows. Presenters work on camera, often photographed in far-flung locations; they address the audience directly, engage in conversation. Carl Sagan’s “Cosmos” is the classic American example of the form, a series that made Sagan virtually synonymous with science television and created new generations of potential Sagans; Anthony Bourdain’s would be the best recent American example of this sort of series. (Ken Burns may be a marquee name, and a not-unfamiliar face, but he is personally invisible in his films.) Such programs have a quality of being authoritative yet open-ended. And quite often they’re funny. Miller, a philosophical man of science with a comic pedigree, was unusually well suited to it.

Miller rejected the oft-applied title “Renaissance man”as a “vulgar journalistic slogan” (“What they’re really saying is I’m a jack of all trades and a master of none”) and could feel that “this footling flibbertigibbet world of theater” was a distraction from higher pursuits — which is to say, the use of his Cambridge medical degree. And yet these interests seem to me less opposed than complementary. If, as is said in “The Body in Question,” “by acting in and upon the world we remodel our own image in it,” everybody’s in show business, anyway.

In a 1990 program titled “QED: What’s So Funny About That?,” he put forth the ideas that we use “the experience of humor as sabbatical leave from binding categories which we use as rules of thumb in order to allow us to conduct our way around the world,” and that the reason we’re attracted to people “is that we know that the fact that they are capable of taking sabbatical leave from the serious categories of life means that they are in fact flexible, versatile and likely to consider things in a different light — in fact, pushed to.” A little wordy for the tombstone, but as good an epitaph, and an explanation, for Jonathan Miller as anyone is liable to write.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.