‘Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback’ review: A closer look at the King’s evolution

- Share via

Television has been the arena for electrifying watershed musical performances — the Beatles on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” Queen at Live Aid, Tony Bennett’s “MTV Unplugged” — that become the stuff of legend: signal moments that are knitted into our understanding of an artist’s life.

But in the long history of the medium, there has been nothing quite as epochal as “Singer Presents … Elvis,” commonly called “The ’68 Comeback Special,” an hour that changed not just the way we looked at Elvis Presley but also the way he looked at himself. The hour fulfills its metaphorical premise, that of a man going forward by going back, reclaiming his roots and his artistry: Elvis redux. It is arguably — barely arguably — the most significant moment in his career, after the day at Sun Studios in 1954 when Elvis, backed by his own guitar, Scotty Moore‘s electric Gibson ES-295 and Bill Black’s double bass, got real gone for a change.

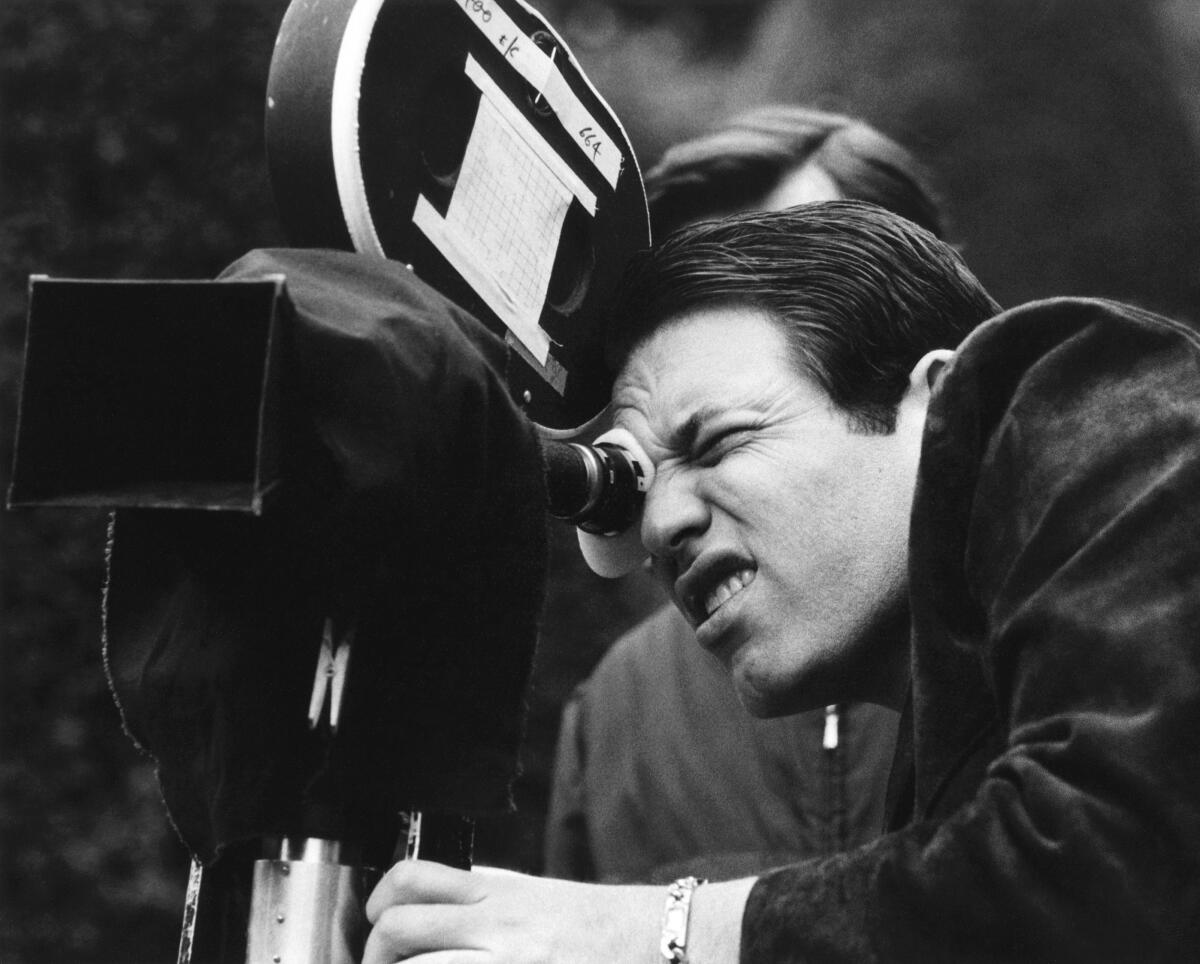

The program has become the subject of a new documentary, “Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback,” premiering Tuesday on Paramount+. Directed by John Scheinfeld, the film is based largely on the reminiscences of executive producer Steve Binder, who directed the ’68 special and with whom Presley formed a bond of trust to the oft-reported displeasure of his territorial manager, Col. Tom Parker. Binder, whom Parker would interchangeably call “Bindle,” recalls the embattled production, laughing as he goes, like a veteran far enough removed from the war to appreciate its absurdities.

If it is not the most nuanced telling, especially when it comes to Parker, dramatically represented by a smoking cigar and explicitly labeled “The Villain” (where Binder is “The Hero” and Presley is “The Star”), the documentary has an easy, anecdotal charm and acts as a welcome corrective to Baz Luhrmann’s scrupulously mimetic, factually whimsical biopic. Fans, it goes without saying, will want to see it.

I know the special almost by heart, having worn out a bootleg copy on VHS years before it became officially available. I was young enough to have grown up on Hollywood Elvis, having seen his later films in movie theaters and earlier ones on television, and when the special was originally broadcast, I had no notion that his career (as Binder told the singer) was “in the toilet.”

And yet, with whatever knowledge or history you approach the comeback special, there is no denying its pure existential force, the committed performance, the claim to be heard, the surrender to the moment. As organized as some of it needed to be — there are complex, choreographed production numbers — the tenor is of real things happening in real time. This is especially the case when the star, clad neck to ankle in black leather, performs to a live audience in the round, sitting in a circle with friends, including Moore and Fontana, playing the old songs, seemingly for his own enjoyment.

For all its complications, Presley’s career does describe a neat arc, a hero’s journey of birth, death, rebirth, decline, ascension. There is the hillbilly cat who came from humble beginnings to change history; the two-year Army interregnum, which coincided with (but did not cause) the oft-predicted, if temporary, exhaustion of rock ’n’ roll; a post-service career drowned in a string of increasingly dismal motion pictures and a growing sense of alienation; the TV special, in which Elvis, facing an audience for the first time in seven years, gets gone again, inspiring a newly serious return to the studio and to the stage. And then the long decline, to the accompaniment of prescription drugs, binge eating and bad advice — even as his acolytes raise him to a state of godhead, the Sun King of rock ’n’ roll.

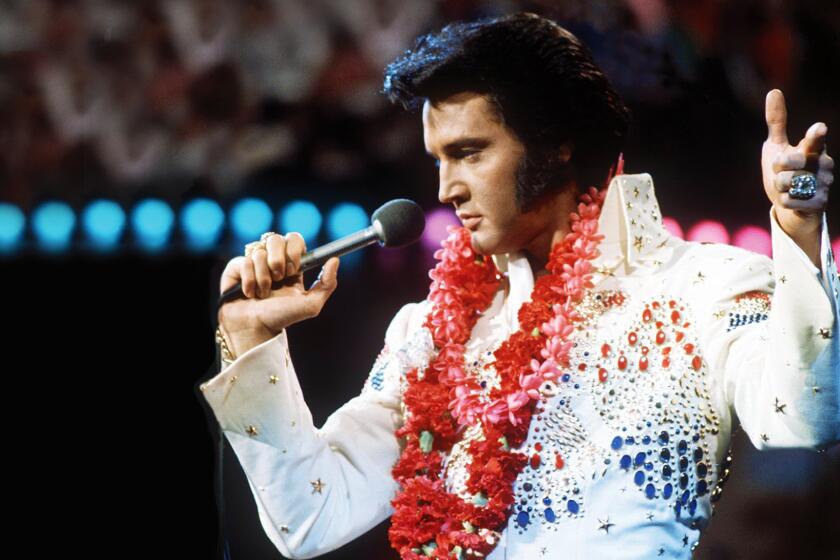

The famous 1973 concert, beamed around the world to a global audience, gets a lavish reissue in the wake of the smash success of Baz Luhrmann’s ‘Elvis.’

It is Elvis 101 that what Parker envisioned as a conventional Christmas special became instead a challenge. (The first words we hear Presley sing-speak, his face filling the screen, tough and insolent, are, “If you’re looking for trouble, you’ve come to the right place.”) Less familiar details include the fact that the NBC deal was a byproduct of Parker’s attempt to finance an Elvis film, and that he turned down Dean Martin’s plush dressing room in favor of a “broom closet” next to the stage where the special was being produced, posting two William Morris agents dressed as British beefeaters at the door. (Photographic evidence is offered.) I never knew or had forgotten that the “sit-down” segment was inspired by Binder eavesdropping on Presley’s dressing room jam sessions.

As the declared hero, we learn something of Binder’s own career — work for the NAACP led to “The T.A.M.I. Show,” a 1964 live concert, originally broadcast to theaters, that included appearances by the Rolling Stones, James Brown, the Beach Boys and the Supremes, which led to NBC’s prime-time pop show “Hullabaloo.” Before “Elvis,” he helmed network specials for Leslie Uggams and Petula Clark that established him as a director who exercised about as much control as was possible in late-’60s TV, and a little more than that: When, during filming of the Clark special, sponsors grew alarmed that Clark, a white woman, took the arm of guest Harry Belafonte, a Black man, as they sang together, Binder wiped all the alternate takes to ensure that that version would be left in. (Indeed, the moment proved controversial.) It convinced executive producer Bob Finkel that Binder was the man for the job.

Binder’s testimony is accompanied by a clutch of “Comeback Special” survivors — dancers, choreographer Jaime Rogers, screenwriter Allan Blye, audience members — and a collection of scholarly and journalistic voices, most vividly Parker biographer Alanna Nash, who had first-hand experience of her enigmatic subject. (She stops just short of accusing him of murder.)

The inclusion of musicians Darius Rucker, Drake Milligan and Maffio to represent Presley’s ongoing influence makes some sense — something for the youngsters, as Sullivan liked to say — though their abbreviated performances of Elvis-associated tunes are quite beside the point.

Presley was 33 — still young, but at a time when “don’t trust anybody over 30” was a counterculture mantra; he was revolutionary in his age, but those battlements had long been dismantled. At the same time, the culture was primed to remember the ’50s.

The following year, Sha Na Na would get famous at Woodstock, Richard Nader would stage the first Rock and Roll Revival concert and John Lennon would open his set at a Toronto rock festival with “Blue Suede Shoes.” Soon came “American Graffiti,” “Grease” and the Fonz.

The special is both a summation and a preview. Presley is the Elvis you see in old 1950s TV clips, flashing the sneer that becomes a smile, the smile that slides into a sneer, but newly mature. He never looked better — perhaps no human ever has — still pretty (his long lashes cast shadows on his cheeks), but sculpted. If it’s a matter of taste to say he never sounded this good, he never sounded exactly like this, before or after. The old songs, in supercharged arrangements, are delivered with a ferocious energy; there is a weight to his voice, which he pushes at times toward distortion. He’s an animal let loose from a cage, a little wary, but excited to be out.

Those familiar with the Singer “Elvis,” or the Luhrmann “Elvis,” or, for that matter, the 2005 CBS miniseries “Elvis,” will not be surprised that, like the special itself, the documentary closes with Presley’s performance of “If I Can Dream.” Written to order late in the production by choral director Earl Brown in response to a difficult, dark, violent year, it filled the slot that in an early schedule had been described as only “Original Big Ballad (Words to Come).” (Parker had hoped to see “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” in that slot — not, as in the Luhrmann biopic, “Here Comes Santa Claus.”) Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated while the show was in preproduction; Binder recalls sitting up with Presley nearly until dawn talking about the state of things.

In a white suit, alone on a stage before his name in lights four stories high, the singer offers a proposition, a plea, a prayer, not to a higher power but to whatever there is in human beings that might make a better world. Something more than a performance, it gives us an artist in full command of his powers letting something move through him, and move him. It is full of desperation and hope, and it does not settle for nostrums. I have watched it dozens of times; it never fails to wreck me, and I suppose it always will.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.