‘Fellow Travelers’ melodramatically charts a gay love story and politics

- Share via

Novelist Thomas Mallon‘s 2007 historical romance “Fellow Travelers,” having been translated in 2016 into a much produced opera, has now become a melodramatic, one might say almost operatic, TV miniseries, created by Ron Nyswaner (“Philadelphia”) and premiering Sunday on Showtime.

Readers of the book, which is set entirely against the Lavender Scare — the gay-targeting companion to the 1950s Red Scare — will recognize its major characters, certain events and even lines of dialogue, but in the service of blowing it up to streaming size, it has been larded with additional decades, settings, character and happenings. As the book took liberties with history (“my usual small liberties with historical fact, and more than my usual license with historical figures,” as Mallon puts it in his acknowledgments), so does the series have its way with the book. Steps have been taken to involve its players — some quite altered — more closely, even heroically, in big political events; to keep the drama on the boil; and to strike a more inspirational note at the finale than does the novel. Politics, which play a large part in the original — and in nearly all of Mallon’s books — are here stripped down to the greatest hits of McCarthyism.

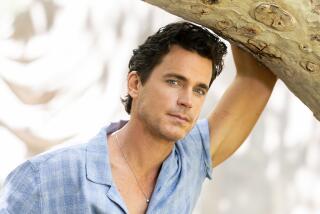

More or less the people they are on the page are main characters Hawkins “Hawk” Fuller (Matt Bomer) and Tim “Skippy” Laughlin (Jonathan Bailey). (Everyone calls Fuller “Hawk,” but only Hawk calls Tim “Skippy.”) Hawk is the Don Draper of the piece — tall, dark and handsome, self-assured, self-serving and unable to love — or at least, when we meet him and long after, not particularly interested in it. A moderately ambitious State Department middle manager, working in congressional relations, he has no politics to speak of, telling Tim, “I’m a registered Republican but I don’t vote because I really don’t see the point, and I feel pretty much the same way about God.”

Tim, by contrast, has a lot of feelings about God, and one particular Republican; as a conservative anti-communist Catholic who reveres Joseph McCarthy, he struggles with his faith and with his sexuality — which Hawk, who passes easily for straight and slides encounters with random rough trade carelessly into his schedule — does not struggle with at all. It is their asymmetrical, see-sawing relationship that forms the spine of the series, with lots of other business tacked on along the way.

Like the book, the series begins in their future. It is 1986. Hawk, who is married to Lucy (Allison Williams, fine and underused), is celebrating his imminent posting to Milan as grandchildren run about the garden. Marcus (Jelani Alladin), a character created for the series, arrives to deliver a meaningful paperweight and the news that Tim, who has been “organizing his life, settling things” is dying of AIDS — and also doesn’t want to hear from Hawk. We then jump back to 1952, when Hawk and Tim first meet at an election night party. We know by his spectacles that Tim is unworldly in all the things in which Hawk is very well versed.

The 1950s and 1980s timelines will alternate through the first episodes; later there are trips to the ‘60s and ‘70s, each with its own complement of wigs, clothes, pop songs and drugs, as we chart the evolution of gay culture and rights as Hawk and Tim, rarely on the same page, come together and break apart — a bit like “The Way We Were,” with a touch of “Brokeback Mountain.” As Hawk, Bomer will not look substantially older as the decades pass; indeed, I had to check the decor and clothing to tell where we were at times. Bailey’s Tim, who goes through many changes, will look remarkably different from era to era. One might reasonably suggest that this is meant to reflect the former’s emotional stasis as opposed to the latter’s progress. It’s a workable theory, anyway.

Back in ‘52, Hawk will meet Tim again, sitting on a park bench with a book and a bottle of milk, and they will have their first real, highly expository conversation. This will lead to Hawk finding Tim a job working in McCarthy’s office, which will lead to Tim giving Hawk a book (a biography of Henry Cabot Lodge in the novel, a copy of Thomas Wolfe’s “Look Homeward, Angel” here, for no clear reason) inscribed “You’re wonderful,” which will lead in turn to them getting into bed together, before and after some more expository dialogue and character-building personal revelations.

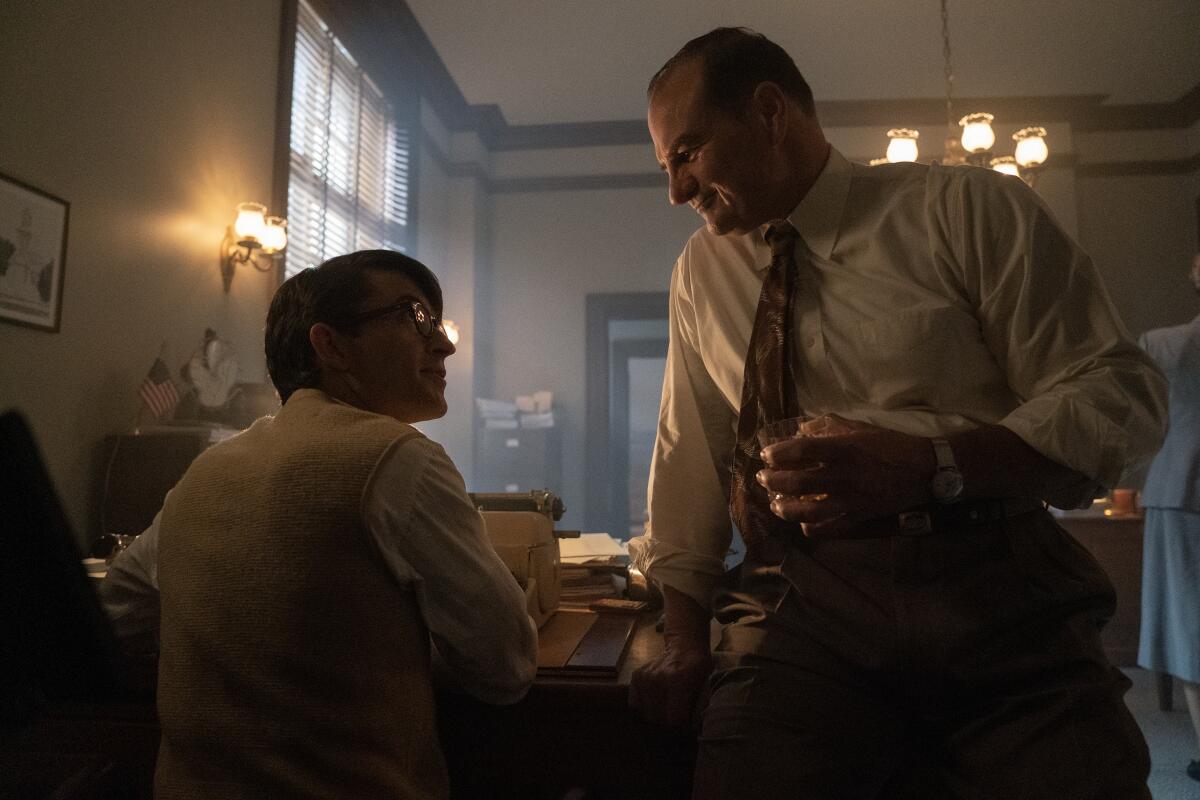

Tim has placed Hawk within McCarthy’s office because he wants a spy there in order to protect his old friend Sen. Wesley Smith (Linus Roache), another Nyswaner invention, who is critical of McCarthy — and, perhaps more important, is the father of Lucy, who we already know will become Hawk’s wife. (Hawk thinks Smith could become president.) That Tim, still a McCarthyite, would tell Hawk anything at all can only be explained by his romantic fascination, just as his fascination with Tailgunner Joe (Chris Bauer, avoiding imitation or caricature) fits uneasily with his homosexuality, now finally finding expression.

Of course, humans are complicated, and for a true-life example we only have to look as far as Roy Cohn (Will Brill), McCarthy’s chief counsel, gay and a persecutor of gays. (I was going to write “closeted,” but in the mid-1950s, you’d have been hard put to find someone who wasn’t.) Cohn, McCarthy and committee consultant David Schine (Matt Visser), who would become the unwitting instrument of Cohn’s fall and McCarthy’s decline — not a spoiler — get a lot of screen time on their own here. It’s something of a distraction from the main business, considering how often their adventures have been documented or dramatized.

Closer to our couple is Hawk’s assistant and confidant Mary Johnson (Erin Neufer), who will also act as Tim’s confidant; her character has been significantly altered (and reduced) from the book, though Neufer makes a strong impression nevertheless. Some of Mary’s narrative responsibilities have been transferred to Marcus — an acidic reporter of the sort you might have found in some 1930s police drama, if he weren’t Black and gay — who gets his own intersecting, insufficiently developed storyline; it does give the series a chance to comment on racism, and to give us a glimpse of Washington’s historically vibrant Black queer scene.

It’s a glossy Hollywood production, with romantic music and handsome people delivering their lines with widescreen energy. And as a glossy Hollywood production about gay life, it is, if not unique — Showtime was also the home of “Queer as Folk” and “The L Word” — still enough of a rarity that one is happy to find it exists. Certainly there are viewers who will see their own lives, or lives they know, reflected in this glass, and you can’t argue with that. Nor is there any denying the historical human tragedy — thousands were fired or forced to resign from government jobs because of their sexual orientation. And there is, it goes almost without saying, a strong resonance with contemporary events, as right-wing theocrats endeavor to roll back LGBTQ+ rights, protections and even presence to some time before this story takes place.

At the same time, “Fellow Travelers” is a somewhat tiring watch. Because we’re aware that our heroes are living dangerous lives, just by living, subject to discovery and humiliation and loss of jobs, standing, family and friends, even scenes that are less than capital-D dramatic are fraught with tension; whenever Hawk and Lucy share the frame, you can only think, “Liar!,” no matter what’s happening. As the series draws closer to the end, coursing through the ‘60s and ‘70s and into the climactic 1980s — making its evolving political points, setting up its reckonings, redemptions and resolutions — the more facile and artificial it can seem.

That’s not to say it isn’t sincerely made or deeply felt. I suppose what I mean is that the series could afford to be a little boring now and again, not like a bad TV show, but in the way life is much or most of the time, in between the towering highs and abysmal lows — where “Fellow Travelers” largely lives. That’s what Tim wants with Hawk, after all — some kind of ordinary domesticity. But we know from the beginning, and are told and told again, that’s never going to happen.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.