Review: ‘Falstaff’ dramatically flawed but musically bracing

- Share via

Los Angeles finally has its first new “Falstaff” in decades. We’re not alone.

Verdi’s last opera, for some of us the finest comic opera and finest Shakespearean opera of all, a marvel of transcendent late style, is an obviously enticing way to end the Verdi year celebrating the 200th birthday of Italy’s greatest composer. Last month, San Francisco Opera replaced a decades-old production with a new “Falstaff” mounted for Bryn Terfel. Next month, New York’s Metropolitan Opera will replace a decades-old “Falstaff” with a new production to be conducted by James Levine.

But L.A.’s old “Falstaff” was more than just old, it was in the actual DNA of Los Angeles Opera. Created in 1982 by the Los Angeles Philharmonic for its music director, Carlo Maria Giulini, the production gave the city a craving for homemade opera in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion that led to the formation two years later of a resident Music Center opera company. Ronald Eyre’s sophisticated and conventional staging then entered the repertory of the new company, and there it remained until it got old and ratty and, in the hands of new directors, coarse and slapstick.

Thus, a new “Falstaff” has the significance of a rebirth. Plus it gets added weight because L.A. Opera, in its economic rebounding from its ambitious “Ring” production three years ago, has mostly been importing its new productions. This first “Falstaff” in L.A. for the company’s music director, James Conlon, is in his DNA as well: It’s one of the first operas he saw as a kid and also the first opera he conducted professionally. A lot is on the line.

The new L.A. “Falstaff” is, like the old one, by a British director. Lee Blakeley has, moreover, stuck within tradition, but his tradition is that of Shakespeare. Maybe too much was on the line or maybe the company needs time to regain its touch for interesting work, but Blakeley has — and this is hard to believe — actually moved the clock back to the bad old days.

One of the reasons Eyre’s production had initially proved of such importance was because it eloquently rose above the cheap tricks of a jokey “Falstaff” that New York City Opera had brought years earlier to the Music Center. In that production, the orchestra pit represented the Thames and Falstaff, when dumped into the river, emerged from the pit dripping wet and with a fish in his mouth.

Here, Blakeley made the pit the Thames and had Falstaff, when dumped into the river, emerge from the pit dripping wet. The one difference, perhaps in deference to pollution or over-fishing, was no fish.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Adrian Linford’s sets and costumes evoke Stratford-on-Avon. A scrim designed like parchment serves as a curtain and is used to project lines from Shakespeare. But the genius of Verdi’s “Falstaff” is that, while devoted to Shakespeare, it is a new invention. The aging, amorous fat knight finds himself in a shifting world, where young love flits by out of reach and nature is inexplicable in ways only music can express.

Arrigo Boito’s libretto uses Italian with individual wit and flair. Referring back to the source, as if this were Shakespeare set to music, actually weighs “Falstaff” down.

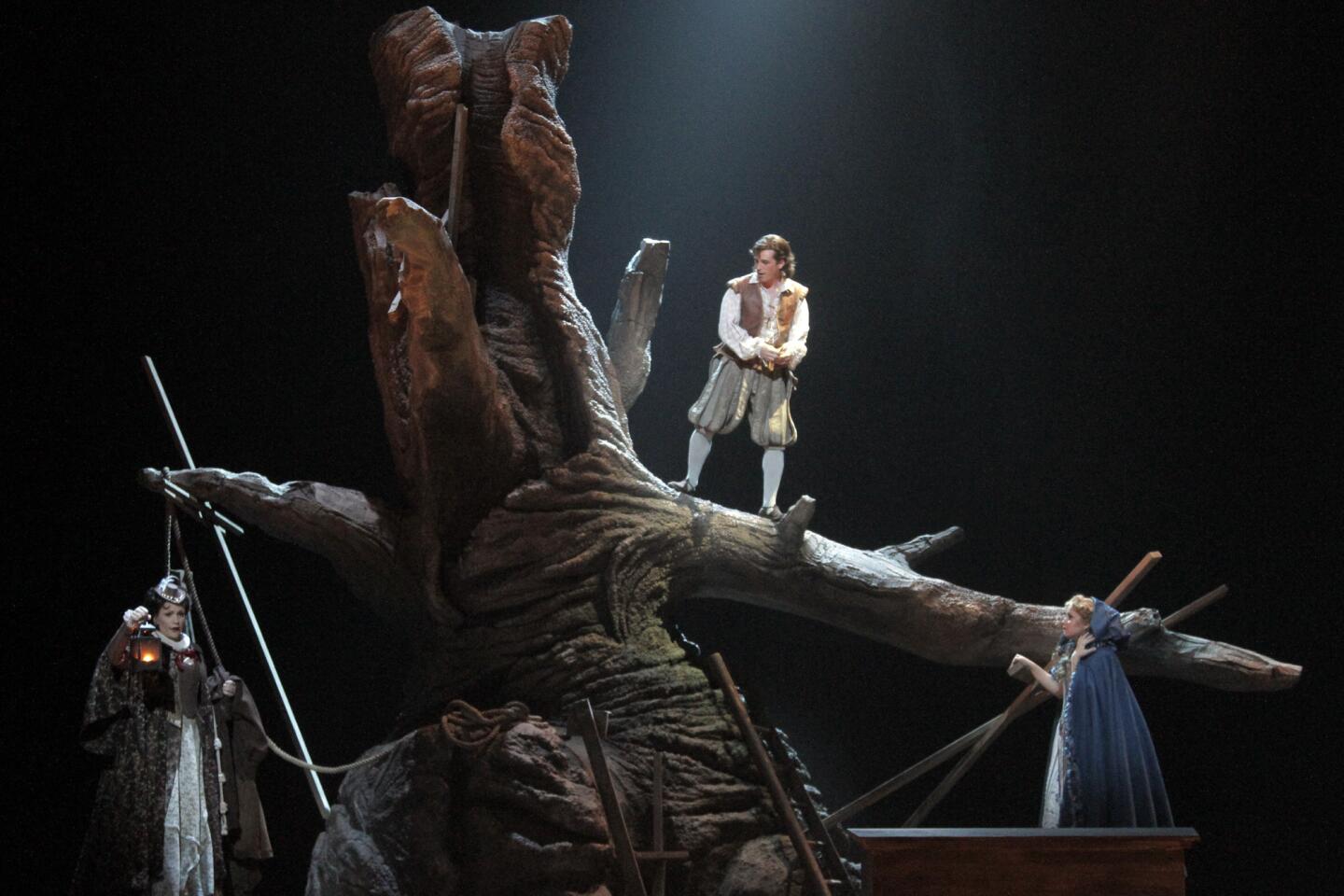

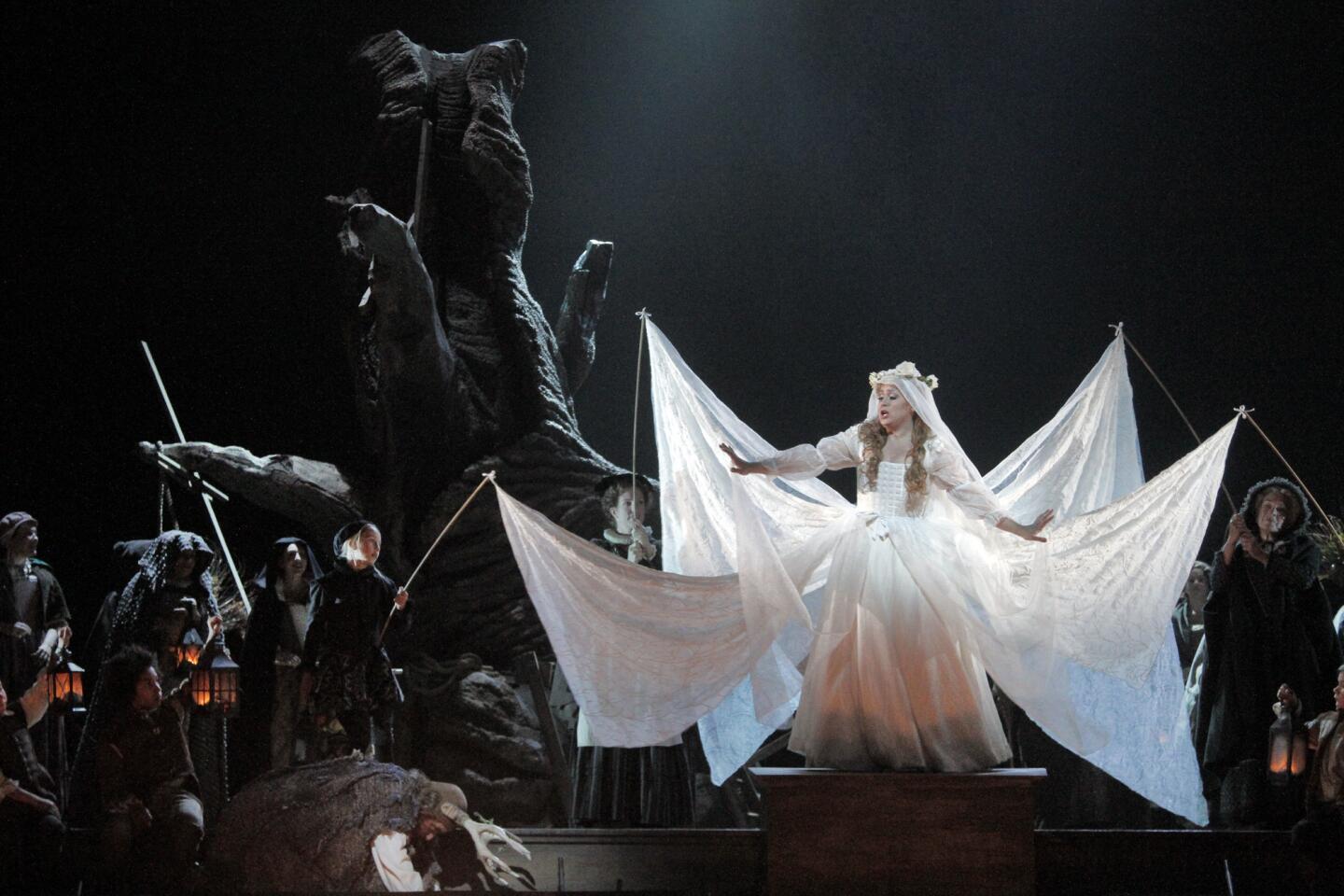

In fact, the trick to staging “Falstaff” is simply to keep up with Verdi’s magically mercurial score. Broad humor doesn’t work. Verdi’s Falstaff is not uncouth but charismatic. Blakeley keeps the stage bustling, does make Falstaff uncouth and relies on conventional operatic comic shtick. The forest scene at the end offers little more than a diseased oak tree and dull lighting, although there is a nice trick with the skirt of the Fairy Queen.

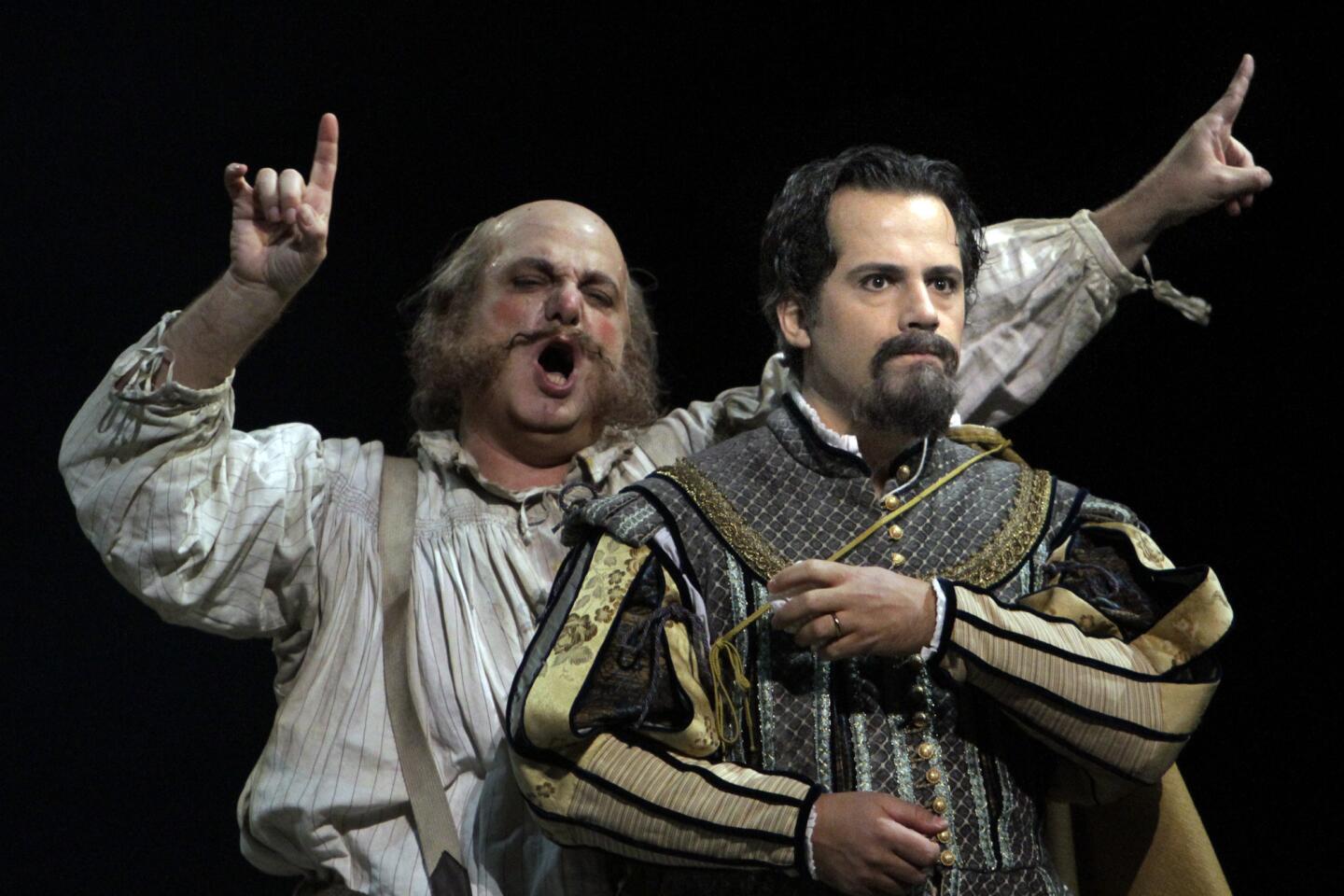

Under Conlon, though, this proves musically a satisfyingly professional “Falstaff.” Italian baritone Roberto Frontali is a decrepit Falstaff, gruff and a little too pathetic, not entirely unsympathetic but a clown. He compensates by singing with strength, anger and a capacity for dramatic outbursts.

Soprano Carmen Giannattasio (Alice) and mezzo-soprano Erica Brookhyser (Meg) are sprightly as the scheming objects of Falstaff’s attention. Baritone Marco Caria is a properly threatening Ford, Alice’s jealous husband. Soprano Ekaterina Sadovnikova and tenor Juan Francisco Gatell as the lovers Nannetta and Fenton are but not light. The buffo characters – Dr. Caius (Joel Sorensen on Saturday night), Bardolph (Rodell Rosel) and Pistol (Valentin Anikin) — are required to repeat antiquated operatic buffo buffoonery.

CHEAT SHEET: Fall arts preview

Ronnita Nicole Miller, however, is the model. She does not overdo the comedy of Mistress Quickly and instead lets her increasingly impressive creamy mezzo do it for her. Having come up through the ranks of L.A. Opera, she gets better with each appearance.

Verdi’s use of the orchestra is one of the opera’s greatest glories, and on Saturday there were enough gorgeous solos to go around. Conlon’s propulsive urgency added weight, but crucial orchestra transparency was lost in the deep pit.

The opera ends with an intricate fugue, in which cast and chorus sing of folly. It is one of the hardest things musically and dramatically in all of Verdi to pull off. This L.A. Opera pulled it off. There was no more nonsense but rather real fervor and a sense that, maybe, just maybe, as this run continues, the characters will start to come into focus and drop some of their superficial silliness.

At any rate, the fugue provides a reason to return after intermission.

------------------------------

‘Falstaff’

Where: Los Angeles Opera, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion,

When: 7:30 p.m. Nov. 13, 16, 21 and 2 p.m. Nov. 24, and Dec. 1

Cost: $20-$311

Info: (213) 972-8001 or https://www.laopera.com

Running time: 2 hours, 30 minutes

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.