Restoring the portrait of an artist: How a new exhibition is giving William Merritt Chase his due

- Share via

Reputations can fall swiftly in the world of art, sometimes in mysterious ways. But few have fallen so far and remained so hidden as William Merritt Chase.

Art historian John Davis reports that in the 1880s, when Chase was just in his 30s, “he had come to dominate the American art scene.” Many Americans hailed him as their finest artist. Many Europeans agreed.

But in the last hundred years since his death, almost all this adulation has dissipated. He is no longer a household name. Americans who know something about his contemporaries and friends James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent usually know nothing about William Merritt Chase. Patrons rarely rush to museums to see a Chase.

Yet while the general public lost interest in Chase, the artist did keep special admirers. A small band of historians, curators and artists — many of them experts in 19th century American art — have tried from time to time to mount shows, some small and very specific, some rather large, to entice renewed interest in Chase. The latest, a large retrospective titled “William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master,” opened at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., this month and goes on to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in October and the International Gallery of Modern Art in Venice, Italy, in February.

Visitors may be surprised at the variety of the 70 paintings and pastels in the show, including his historical portrait of a European jester snorting a bit of wine to prepare for his act (“‘Keying Up’ — The Court Jester,” 1875, which won a prize at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial fair and is now owned by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts) and beach scenes on Long Island in New York.

Chase, who was born in Indiana in 1849, the son of a shoe store owner, studied art in Munich, Germany, and intended his works to fit into the long tradition of European painting. So his vast output included scenes of Venice, self portraits, paintings of his own studio chock-full of bric-a-brac, nudes and still lifes so realistic that collector Duncan Phillips once wrote, “he is unequaled by any other painter in the representation of the shiny, slippery, fishiness of fish.”

But Chase also applied the techniques of European artistry to American subject matter and experimented with new techniques, creating wonderful Impressionist landscapes of New York City’s Central Park and the new parks of Brooklyn, studies of modern American women at rest, unsettling pictures of children at play, and everyday scenes of the backyards of Brooklyn homes.

His American mood and fresh ideas produced such masterpieces as “A City Park,” an Impressionist landscape of the new Tompkins Park in Brooklyn; “Hide and Seek,” a mysterious interior painting of two girls playing, seen only from behind; and the haunting red and black portrait “The Young Orphan,” painted in the style of his friend Whistler’s arrangements of color, especially in the famous painting of his mother, now in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

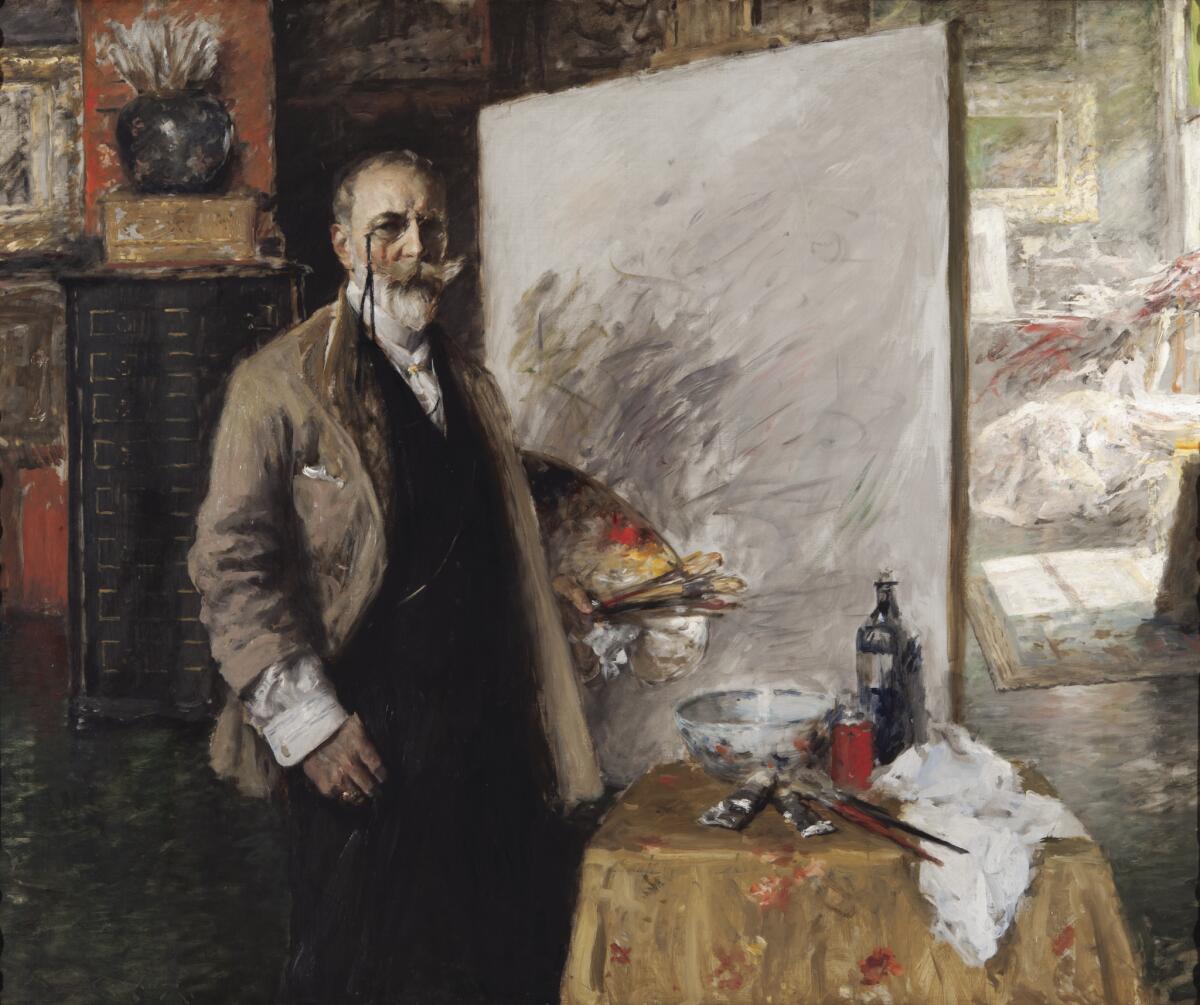

Chase believed that Americans should accord artists a special place in society, and he engaged in a good deal of theatrical self-promotion to help achieve this. He did not dress like an impoverished bohemian artist but like an eccentric grandee. He sported a walrus mustache, a high French silk hat, an expensive suit and a thick black ribbon for his pince-nez eyeglasses. He usually walked the streets of New York with a white Russian wolfhound. A servant in a fez and Turkish pantaloons sometimes followed them.

Chase also insisted that a sumptuous studio full of props for portraits and for costume parties should serve as a vital part of the elegant artist’s insignia. He rented a large space with a second-story balcony in the Tenth Street Studio Building in New York. Albert Bierstadt had used the studio earlier to paint his enormous Western canvases. Chase’s props, which show up in some of his paintings, included Japanese fans, tapestries, 37 Russian samovars, a bust of Voltaire and a stuffed flamingo. Chase held open house every Saturday, attracting students and fellow artists.

Using his favorite nickname for his friend, Whistler once told Chase, “After all, Colonel, the only real objection I have to you is that you teach. You’re just like all these others — the vulgar crowd.” Chase, in fact, taught classes throughout most of his career. Augmenting his income was the main reason he agreed to teach at the Art Students League of New York in 1878 when he was 29. But he enjoyed performing in a classroom and soon decided that teaching was an essential part of helping to create a culture for art in America.

He had come to dominate the American art scene.

— Art historian John Davis on William Merritt Chase

Chase also taught at other institutions, including the Brooklyn Art School, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the Summer School of Art that he directed at Shinnecock Hills in Southampton on Long Island, and the Chase School of Art on 23rd Street that changed its name to the New York School of Art after he sold it. In his last years, he would also teach summer courses in Europe.

As a teacher, Chase sometimes painted a portrait or a landscape, then handed it to a deserving student. Some students would soon bask in fame themselves. Georgia O’Keeffe said “there was something fresh and energetic and fierce and exciting about him that made him fun.” Edward Hopper noted on his business cards that he had been “a student of Chase.”

But Chase’s enthusiasm for teaching was also used against him. As a professor, he wanted young students to learn the basic principles of drawing and coloring before trying their hands at anything experimental. That made Chase seem somewhat stodgy, old-fashioned, out of touch.

A climax came in 1913 when artists and critics put together a massive show of recent trends in European and American art at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York. This exhibition, known in art history as the Armory Show, introduced modern art to America. Americans could witness Cubism and the special coloring of Henri Matisse without traveling to Europe. But for Chase the Armory Show was a slap in the face. The sponsors did not ask for a single canvas from him.

Chase visited the show six times, and each visit seemed to increase his anger. In lectures he accused Matisse of “charlatanry” and the sale of Futurist paintings as “a gold brick swindle.” He joked that Cubist paintings should be hung upside down — if they had an up and a down. “I have tried in vain,” he said in another lecture, “to find out what the aim of it all is.”

Audiences laughed at his diatribes, but his anger troubled young critics who had been seduced by the new ideas coming out of the armory show. One belittled Chase’s views as “typical of the minor academic painters and the critics who view art through the eyes of the past.”

Chase died at his home in New York in 1916 at age 66. His views on the need for realistic art never changed. As the Phillips Collection’s Elsa Smithgall, curator of the Chase exhibition, puts it, “His approach to art gets eclipsed by the new art of abstraction, and he falls out of favor very quickly.”

The fall, in the view of Smithgall, was too deep. The subtitle of the show, “A Modern Master,” is a kind of cry of defiance. Smithgall insists that Chase was an experimenter who tried to depict the new currents of life in the United States like the growing freedom of women and the creation of new parks in the cities. ”He is,” she says, “quite a revolutionary.”

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.