Playwright Molly Smith Metzler’s ‘Cry It Out’ takes a hard look at motherhood

- Share via

The conversation comes quickly, spills from the women’s mouths, words filled with relief and infused with mutual understanding: of sleepless nights, of profound anxiety, of bodily fluids run amok, of a feeling of helplessness. And love. Great, big, boundless love. The love a mother feels for her child.

“When I see other women who are moms now, I bow down,” says one woman.

“At the airport, I’m, like, ‘Can I grab that bag for you?’” says another.

“Random things make me cry, like ‘America’s Got Talent,’” another blurts out. “I used to be an ice queen. I cry all the time now.”

“Oh, my God. ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’!”

“’Manchester by the Sea’!”

“My daughter is 5 and a half and I feel like my body is still recovering from surgery.”

“It’s the hardest thing I’ve done. I’m a shell of a human being. And then postpartum anxiety. Nobody mentions that. It’s supposed to be rainbows and butterflies.”

“In every movie I’ve seen since I had a kid, the baby is in the bassinet quietly cooing and I scream at the TV. ‘Who is writing this? They have never had a baby!’ A baby has never cooed quietly in a bassinet. Ever.”

This is not a mother’s support group. The women in this conversation are all creatively integral to the production of a new play by Molly Smith Metzler: “Cry It Out,” being given its West Coast premiere at Atwater Village Theater in a production by the Echo Theater Company.

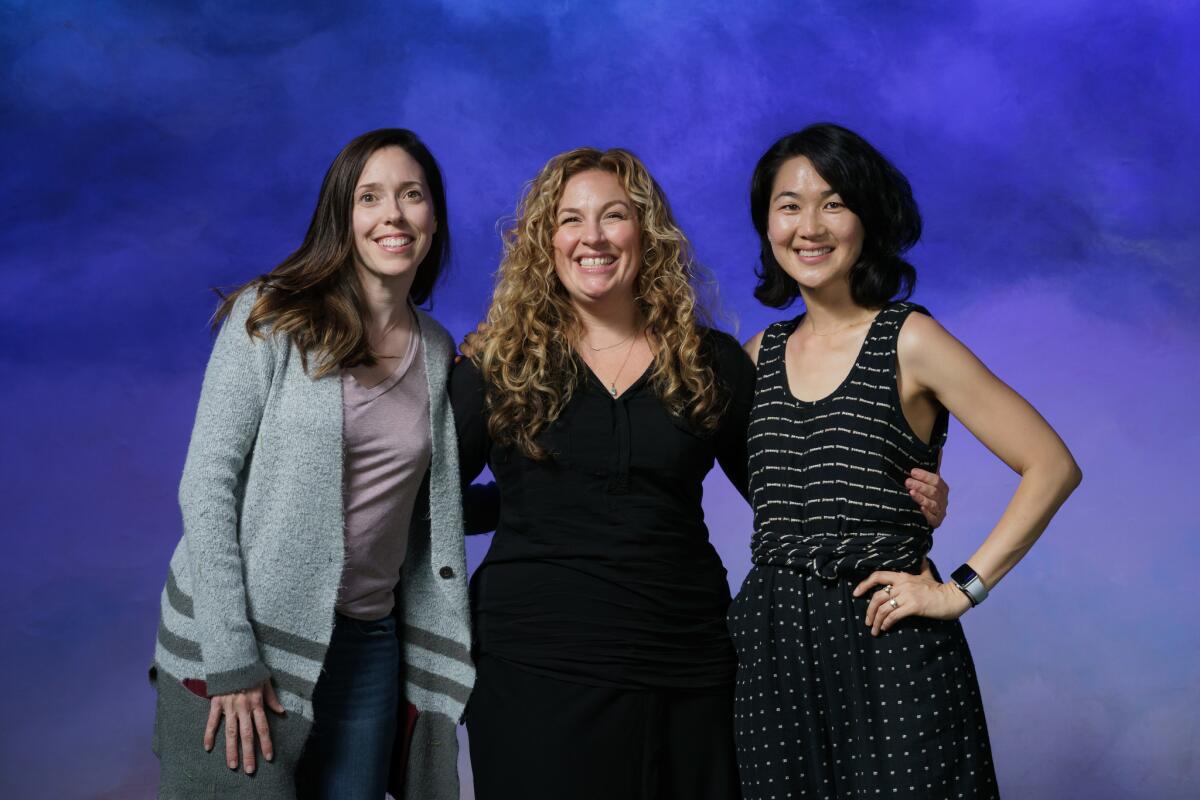

Sitting in a circle on the diminutive set are Metzler, mother of 5-year-old Cora; director Lindsay Allbaugh, mother of 7½-month-old Miles; and costar Jackie Chung, mom to 3-year-old Bodi.

Pop culture, they say, often comes up woefully short on this subject — leaving babies in the background, as secondary players rather than the dominant, totalitarian drivers of household narratives.

They are all bound and determined to speak truthfully about motherhood.

Allbaugh has been pumping breast milk during rehearsals, and Chung took two years off from acting — more out of necessity than choice — before getting back into the swing of her career. “Cry It Out” is the third play she has performed since Bodi was born.

Their stories have proved vital to the staging of the show, which is based on Metzler’s own experience; as a new mom she moved to a small town on Long Island with her husband, who worked all day while she stayed home with their infant daughter. They had no money and no childcare, and Metzler felt depressed and isolated. She finally befriended another mom, a woman she credits with saving her life just by being there.

“Cry It Out,” explores the friendship between two newly minted moms as they struggle through a frigid winter in a working-class town. A third mother, from a rich enclave in the hills above, infiltrates their coffee klatch, bringing a certain measure of negativity, as well as some hard truths into their insular mom-bubble. Each woman faces some crushing choices when it comes to balancing her life and her work with new responsibilities as a mother, and there is not a happy ending.

Money — or a lack of it — looms large in the script, as the women are afforded different choices according to the size of their bank accounts, an uncomfortable truth of parenthood that Metzler feels is not often talked about in this country.

That, and the fact that preparing for an incoming child is, by default, almost always a woman’s problem.

“You have no idea what you’re getting into when you have a kid,” Metzler says. “You have no idea it’s going to crack your life open, it’s gonna crack your identity open, it cracks your marriage open, it cracks your career open, and in my case it actually physically cracked me open.”

Allbaugh and Chung nod, smiling slyly.

Both women’s children are on set for a photo shoot this afternoon, along with Metzler’s daughter, Cora, who arrived with some paper cutouts she had made: an iced coffee, a laptop and a cellphone. Cora set these up next to her mother’s matching tools, saying she was a “Mom work artist.”

Cora also appeared to experience a near pathological draw to the stage — which features a patch of leaf-strewn grass and a small, plastic, child’s playset — and ran onto it a few times, smiling broadly and giggling manically.

Her enthusiasm was met with warmth and pride. The children were getting a taste of what makes their mothers creative professionals; and the mothers were being reminded of why what they do is so important. They were modeling art and commitment to their offspring while straddling a sometimes impossible divide between self-care and total devotion to another living creature.

Motherhood, the women say, has forever altered them; and doing this play is both cathartic and hugely important because it sheds light on certain realities often relegated to the shadows, including how women can judge one another’s choices unfairly, and how that judgment affects women emotionally.

Of particular interest to Metzler, and the play, is what she says is the tragically short amount of time that mothers are allowed for maternity leave in this country, and how impossible it is to sort out all the attendant issues, financially and otherwise, of new parenthood in that small window.

“Cry It Out” begins and ends with a question that goes unanswered, Metzler says, out of empathy for the deeply personal nature of each possibility.

“The point of the play is that what we do as women is lose-lose,” Metzler says. “You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t. You will always question your decision. There’s so much societal pressure to have it all, and having it all is a lie. It doesn’t exist.”

Metzler didn’t have the energy or capacity to write about her experience when Cora was an infant.

“People talk about babies like they are just going to slide into this life that you already have,” Metzler says. “And everything changes and you don’t necessarily have choices, which is something I experienced and witnessed in some of my new friendships, and I really felt like that question belonged onstage.”

She began writing “Cry It Out” when Cora was 2 and finished two years later. During that time she also transitioned from being an underpaid playwright to writing for television (“Casual” and “Shameless,” among others). By the time she wrote the play’s final scene, she was living in a sublet in Los Feliz, 2,500 miles away from her daughter.

Her choice to commute to Los Angeles when Cora was a toddler was often judged harshly, Metzler says, adding that if she had been a man making the same choice, it would have been judged quite differently, and that’s another issue she explores in “Cry It Out.”

Allbaugh first read “Cry It Out” when Miles was 2 months old. She was exhausted, covered in breast milk, and had been wearing the same pajamas for a week. She thought she’d get in a few pages between naps and feedings, but once she started she couldn’t put it down.

“I was, like, ‘I’ve never seen a story like this onstage,’ and I’ve never felt so connected and so reflected in the pages of a script,” says Allbaugh.

A member of Center Theatre Group’s artistic staff, she had gone back to work full-time when Miles was 6 months old. “I was still in the thick of figuring out how to be a mom and dealing with postpartum anxiety and wondering if I would ever be able to direct a play again.”

Thanks to a supportive work situation and the indefatigable help of in-laws who drive up from Orange County to babysit whenever necessary, Allbaugh found that she could take on the project. And she feels great relief talking and commiserating with the other mothers on set.

Chung is equally thankful for the camaraderie and understanding that she has found during rehearsals. Her pregnancy was a surprise and happened just as she had moved to Los Angeles and was attempting to get her acting career off the ground. Theater in Los Angeles is a notoriously low-paid calling, so she found that she had to say no to all kinds of projects because she would be paying more for child care than she would be earning for her work.

“Mothers are the most amazing people. We are superwomen, all of us,” Chung says. “We are all doing the best we can — the best for our child, and every day it’s, like, ‘How am I gonna do this?’ But we do. And I have come to see that my child is very resilient.”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Cry It Out’

Where: Echo Theater Company at Atwater Village Theatre, 3269 Casitas Ave.

When: 8 p.m. Fridays, Saturdays and Mondays, 4 p.m. Sundays; ends Aug. 19. On July 22, free child care to parents attending the show.

Tickets: $34; Mondays, pay what you want

Info: (310) 307-3753, www.echotheatercompany.com

ALSO:

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.