Critic’s Notebook: A new blueprint for architectural excellence

- Share via

Do you know the Monuments Men?

I don’t mean the George Clooney movie with the middling box-office numbers. I mean the male geniuses, according to architecture’s creaky conventional wisdom, who push the profession forward with one pricey and daring building after another.

The Monuments Men have ruled architecture for a good 500 years, since at least the days Andrea Palladio was designing impressively scaled villas for his clients in Northern Italy. Their prominence peaked about a decade ago, with the well-chronicled rise of the globe-trotting celebrity architect and his small army of publicists.

The women who have broken into this club — and there have been a few, like Zaha Hadid — have usually done so by building bigger and more dramatic landmarks than the boys.

But many in the profession have lately been calling for a broader, more nuanced definition of how architecture operates, beginning with an effort to acknowledge its fundamentally collaborative nature.

Three significant awards this month suggest that the campaign is making headway. Prizes are usually trailing indicators of change in any field, not leading ones. (See: the Oscars and the NAACP lifetime-achievement award that almost went to Donald Sterling.) In this case, the honors offer a chance to measure an emerging shift in how architecture defines itself, a loosening of the Monuments Men’s collective grip.

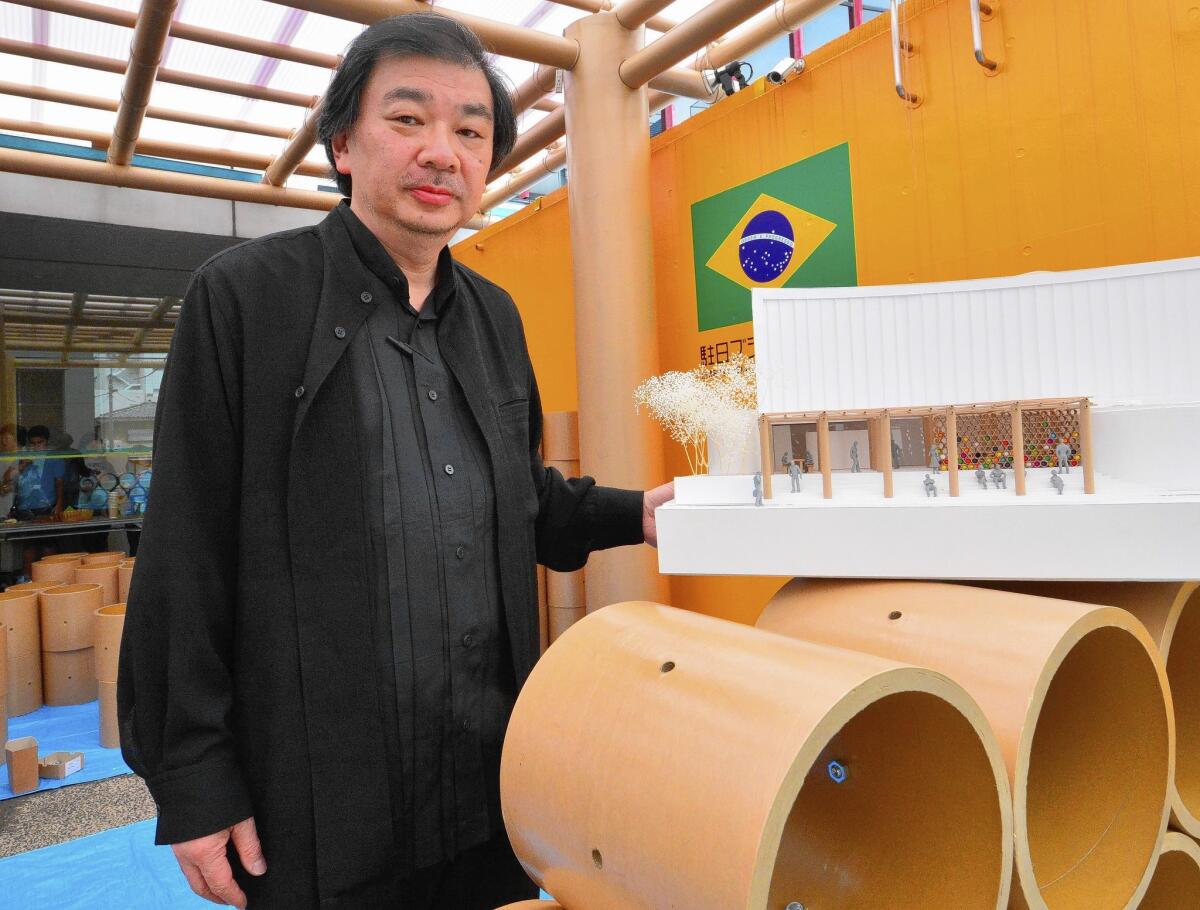

Let’s begin in Amsterdam, where the Japanese architect Shigeru Ban will on Friday accept the Pritzker Prize, the profession’s leading honor, in a ceremony at the Rijksmuseum. Ban is no stranger to architecture’s high-end precincts: He designed a $45-million home for the Aspen Art Museum that will open in August.

But he is best known for his disaster-relief work in Africa, Haiti and post-tsunami Japan. He designs inexpensive shelters and community centers from cardboard tubes and other basic, easy-to-find materials.

The Pritzker jury praised him as an architect “who, for 20 years, has been responding with creativity and high-quality design to extreme situations caused by devastating natural disasters.” Just as significant, it said Ban had “expanded the role of the profession” by bringing thoughtfully designed buildings to sites where bureaucrats and engineers typically hold sway.

Ban’s work is inconsistent. British writer Tim Abrahams had a point when he complained to the Boston Review recently about the “kooky, Middle Earthy, Hobbity” quality of Ban’s larger projects, especially his top-heavy branch of the Pompidou in Metz, France.

Ban’s Pritzker case is strengthened by his disaster-relief projects — in particular his simple, assured and light-filled cardboard churches — also being his most convincing architecturally.

At this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale in Italy, meanwhile, director Rem Koolhaas — a Monuments Man for sure, though one whose talent for undermining the profession’s treasured pieties has always been especially well developed — chose to give the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement to Phyllis Lambert, the founder of the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal.

Lambert is not an architect. She is a patron in the broadest and most productive sense of that word. She helped create the CCA, which has grown into the most vital home for architectural scholarship and exhibitions in North America, in 1979.

Before that, while in her 20s, she served as the chief client for one of the most significant breakthroughs in 20th century architecture, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s 1958 Seagram Building on Park Avenue in Manhattan.

The Golden Lion typically goes to a Monuments Man. Its recent winners have included Richard Rogers, Alvaro Siza and Koolhaas.

“I’ve won lots of awards, but nothing like this,” Lambert told Architectural Record. “This is major. Major.”

Even as her award suggested progress, this year’s Biennale hosted a brief protest from young activists who call themselves the Architecture Lobby. They published 10 demands. Many had to do with salaries and licensing requirements; others aimed right at Monuments Men privilege.

Number 6: “Demystify the architect as solo creative genius; no honors for architects who don’t acknowledge their staff.”

And then there is Julia Morgan, the California architect who died in 1957. At the American Institute of Architects national convention in Chicago this month she will become the first female architect to receive the organization’s top career honor, the Gold Medal.

It’s not just Morgan’s gender that makes the award meaningful. Thanks to the legacy of the modern movement and its insistent focus on formal novelty, a remarkably narrow definition of innovation has prevailed in architecture — and shaped the roster of prizes like the Gold Medal — for a full century. It has celebrated stylistic breakthroughs at the expense of all others.

As a result, Morgan, best known for her eclectic, extravagant work at San Simeon for William Randolph Hearst — as well as handsome, more restrained private houses in the Bay Area and women’s clubs around the state — has been seen as a conservative, even retrograde figure.

Yet Morgan’s career was a case study in innovation and daring in every way but the shape of her buildings. Born in San Francisco in 1872, she was the first woman to earn an architecture degree from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and the first to be licensed as an architect by California. She ran her own office for more than 45 years and completed more than 700 projects, nearly all of them in California.

Dozens of the buildings are worth celebrating in their own right. I grew up in a 1920 house designed by Morgan in the Berkeley Hills, giving me a chance to study her poised, materially rich and site-specific approach up close. But it is really the consistency and steadfastness of her output, as an astonishingly prolific pioneer in a field that is still dominated by men, that makes her overdue for a national honor like the Gold Medal.

Do any of these awards represent a sea change, a radical shift? Not quite.

In Ban, the Pritzker found a convenient middle ground: an architect who has made a career smoothly bridging the gap between socially conscious and high-design architecture. He was hardly an obscure or shocking choice.

Lambert’s Golden Lion is a reminder about how much more work will be required to fully understand the role clients have played in producing architecture’s greatest buildings.

Female architects are right to wonder, as many have, why the AIA decided to break the Gold Medal gender barrier by honoring someone who died 57 years ago rather than a contemporary figure like Jeanne Gang or Annabelle Selldorf — or a male-female partnership like the one between Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi or Tod Williams and Billie Tsien.

And as the Architecture Lobby points out, the way the profession pays and licenses its youngest members is as outdated as its tendency to honor the “solo creative genius.” Even worse is its attitude about working conditions for the crews who build high-profile projects in places like Qatar and China.

Still, each of the awards is a meaningful step forward, another chink in the armor of the Monuments Men and the substantial industry that has grown up to keep their places secure. Taken together, they suggest momentum is gathering behind a genuinely new view of how architecture is made and measured.

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.