2017 California-Pacific Triennial at OCMA: The art of building up (and tearing down)

- Share via

The Orange County Museum of Art has used its 2017 California-Pacific Triennial exhibition as an opportunity to meditate on the museum’s potential move to a new facility at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa. The planned relocation from Fashion Island in Newport Beach was first announced nearly nine years ago.

That’s a rather long time. If the project does finally come to fruition, let’s hope the result is better than this mostly bland Triennial.

Twenty-five artists and artists’ collectives from 11 countries around the Pacific Rim have been assembled for a thematic presentation related to the long-aborning move. Curator Cassandra Coblentz set out to consider “what it means to simultaneously build up and tear down architectural structures.”

The most sardonic suggestion comes from South Korean artist Haegue Yang. Out on the museum’s breezy back patio, she’s mounted an air conditioning unit and a couple of turbine vents as nominal sculptures placed atop a makeshift pedestal of concrete building blocks.

As the Earth’s climate continues to heat up — a rise that is poised to make any, and all, of OCMA’s plans ultimately irrelevant — the outdoor air-cooling assemblage gives grim poetic heft to the sheer absurdity of our as-yet stumbling efforts to regulate global temperature. As her wry sculpture proclaims, we are poised to be overwhelmed.

Only four or five other works in the show, which continues through Sept. 3, approach a similar level of engagement. One is a full-scale replica of a Craftsman-style front porch and facade of a house in the northeastern San Fernando Valley.

The house was built around 1923 by Dan Montenegro, an Apache stonemason. Its river rock pillars, tiled flooring and wooden shingles and front door are here rendered by L.A.-based Beatriz Cortez in welded steel and sheet metal. Industrial materials create conceptual friction with the original Craftsman impulse, generated in reaction to the Machine Age assault on skilled craftsmanship.

Given the meteoric rise of the Digital Age, the welded steel façade represents a newly endangered form of skilled craftsmanship. Cortez’s “The Lakota Porch: A Time Traveler” is a blunt sculptural essay in determination not to disappear from memory.

Another disarming work is Oakland-based Cybele Lyle’s room-size installation merging colorful, brightly painted wood strips and video projections. Skinny, vertical wood planks, stacked end on end, rise from the floor and lean against the wall like oversize pick-up sticks.

In this vibrant if precarious space, rudimentary sculptures attempt to stand up and elementary paintings try not to fall. A soundtrack of intermittent crashing noises echoes through the room. The din reverberates like a cautionary memory of earlier failed attempts at constructing the unstable ensemble.

Nearby, a frame-like rectangle of wood strips seems to have partially slid off the wall and onto the floor. Projected through this collapsing picture frame is a big, off-kilter, flickering image of the moon. Lyle’s wobbly romantic space houses the fragility of the heart, as well as the mind.

Speaking of the heart, L.A. artist Olga Koumoundouros presents glass vessels whose bulbous shapes recall internal organs; they’re held aloft on wrought-iron stands like votive lights.

Framed letters hang on an adjacent wall. Koumoundouros, touched by hearing of the recent death of a much-admired, longtime maintenance employee on the museum’s staff, reached out to his widow to ask permission to make this valedictory piece.

Permission granted, she then got down to brass tacks, penning another letter to OCMA Director Todd D. Smith urging fair and equitable labor practices for employees throughout the museum. (Two years ago, in controversial preparation for its planned move, OCMA sliced five positions from its already small staff.) Acknowledging the essential if unsung work of behind-the-scenes institutional wage-earners, her letter further instructs the museum to permanently install one glass vessel outside the director’s office, wherever the building might be, as a perpetual reminder.

When a museum comes knocking, it’s especially noteworthy if an artist does more than merely go along for the ride — and Koumoundouros neatly undercuts the Triennial’s architecturally focused premise. Forget bricks and mortar; the clear implication of her measured installation is that people are the institution.

Chilean artist Pilar Quinteros is on a related path in her idiosyncratic performance video, “China House Great Journey.” The racial politics of immigration is its topical engine.

Quinteros built a model of a Chinese-style house that once stood by the beach in Corona del Mar, just a mile or so from the museum. Starting at the old Santa Ana City Hall, built in an elaborate Art Deco style as a civic employment project during the Great Depression, she dragged the model on the ground all the way to the ocean like some leatherback sea turtle foraging for survival along the West Coast.

Santa Ana was the site of a notorious episode — the 1906 burning of its small Chinatown, motivated by racial animus. ("It was like a big picnic, or a Fourth of July," an eyewitness later recalled of the heinous act, orchestrated by city officials.) Bit by bit, Quinteros’ model busts apart on her cross-county journey; she keeps stopping to tie the broken fragments together into a bundle.

Arriving at the beach, near the site of the original Chinese-style house (except for a fragment, it was demolished in the 1980s), Quinteros reassembles its model as a ramshackle pile of shards — a ruin brought about by time, cruel social history and the fraught politics of immigration. With a swift kick, she erases all that, much the way the nearby China House was itself demolished. The model’s disheveled remnants are displayed on a gallery pedestal.

The performance video is one of the show’s few works to specifically jog thoughts of OCMA’s endless building saga. The current facility, erected in 1977 for a modest sum (around $3 million in today’s currency), smartly prioritized art over a fancy building for its display. Designed by Ernest Wilson of Langdon and Wilson, architects of the original Getty Villa, it employed tilt-up concrete-wall construction methods more common to erecting grocery stores than art museums.

Almost immediately, desire for expansion emerged among some ambitious trustees.

They’ve persisted ever since, waxing and waning with the economy, the region’s growth and institutional staffing; along the way, a fat file of elaborate plans and dashed hopes has grown. Forty years on, it’s doubtful that considering “what it means to simultaneously build up and tear down architectural structures” is a pressing philosophical notion.

Many of the artists nonetheless charged with considering it were commissioned to make new works. Few seemed to get far beyond the research stage. A lot of the art isn’t much more than lackluster show-and-tell reportage of their seldom surprising findings.

OCMA plans to sell its current Fashion Island home to a developer to fund the move. Lead Pencil Studio — Seattle architects Annie Han and Daniel Mihalyo — produced crystal bricks photo-etched with images of barren parking lots. Shown in gleaming, uplighted display cases, they’re more like 1960s Ed Ruscha photographs transformed into 2017 paperweights for the luxury market than some sort of exposé of the retail value of empty land near the beach.

Does that really need explaining?

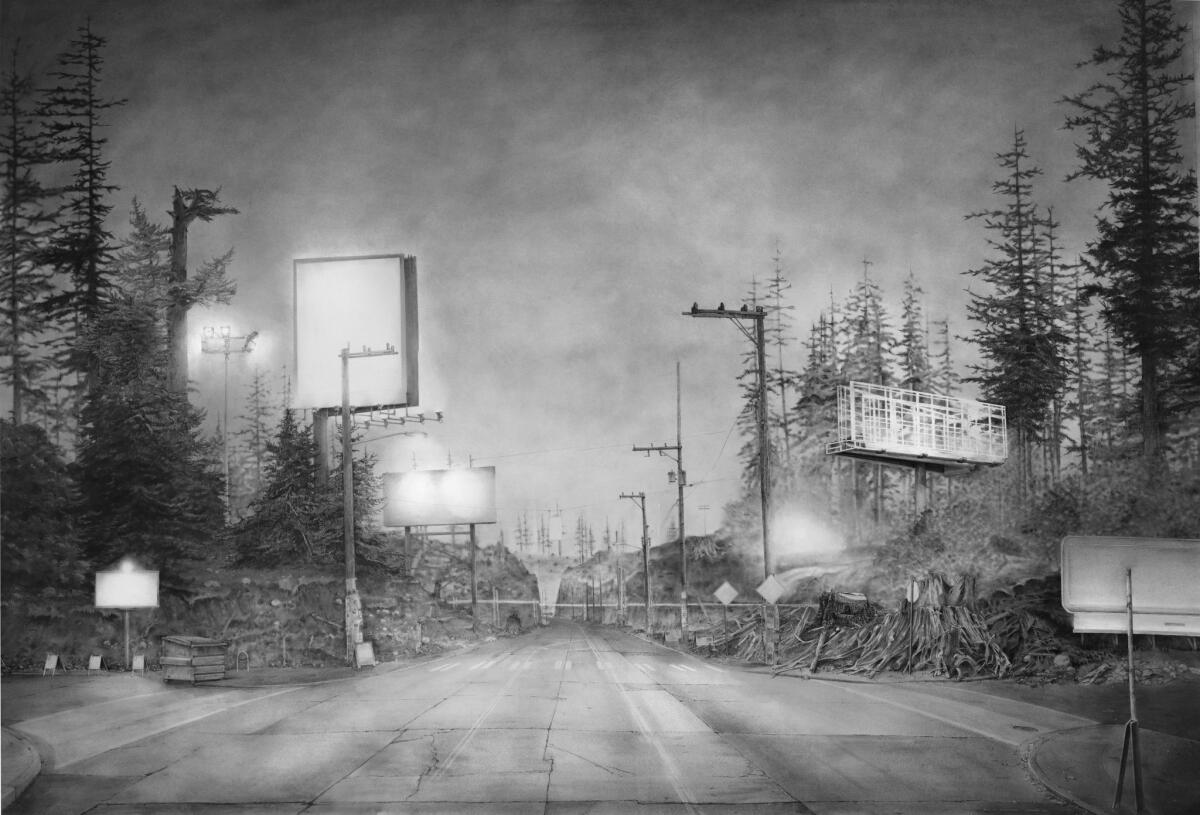

Far more compelling are Lead Pencil’s earlier monumental drawings of collapsing nighttime landscapes illuminated by artificial light. Populated by signage — billboards, street signs — that is uniformly blank, these are places bereft of useful communal guidance, whether public or commercial, and well on their way to ruin.

The drawings, beautiful and grim in equal measure, open up an emotional chasm of imminent and irretrievable loss.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

California-Pacific Triennial

Where: 850 San Clemente Drive, Newport Beach

When: 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesday-Sunday (till 8 p.m. on Fridays); ends Sept. 3

Admission: $7.50-$10 (free on Fridays)

Information: (949) 759-1122, ocma.net

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.