2 Japanese photographers, 2 cultural camps at Getty Museum

- Share via

“Japan’s Modern Divide” at the Getty Museum expands to full scale the classic art history course drill: slides by two artists appear side by side on the screen; compare and contrast.

The show features two mid-20th-century photographers who practiced at opposite ends of the aesthetic spectrum. It could just as easily have been titled Sense and Sensibility. Or, in keeping with the didactic nature of the exercise, Subject and Subjectivity.

Hiroshi Hamaya (1915-99) is far better known in the U.S. than his counterpart, Kansuke Yamamoto (1914-87), and both are outdistanced in recognition and sheer artistic vigor by the generation of Japanese photographers that succeeded them: Eikoh Hosoe, Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama, Nobuyoshi Araki and others. These mini-surveys of roughly 50 prints each (organized by the Getty’s Judith Keller and Amanda Maddox) include strong bodies of work by Hamaya and Yamamoto but also much that is derivative, conventional or simply weak. Neither presents a fully compelling career arc.

RELATED: Asian photos at the Getty Museum

The show’s binary structure sets up the photographers as personifications of divisions within Japanese culture: traditional versus forward-looking; rural versus urban; Eastern versus Western. It’s a bit forced as a curatorial conceit but generates illuminating comparisons nevertheless.

Both artists took up photography as teenagers around 1930, when dynamic new approaches to the medium — Surrealism, New Objectivity, lessons from the Bauhaus — began to infiltrate Japan from abroad. Hamaya started out as a street photographer (using the new, hand-held Leica) in the Ginza district of Tokyo. He produced his best work documenting rural village life in a humanistic mode familiar to photo essays in the newly emergent illustrated magazines of the ‘30s. His style is lucid and unassuming, subject-driven.

He spent more than a decade chronicling the rituals surrounding new year celebrations in northeastern Japan. His project evolved along ethnographic lines, with emphasis on visual information about traditions of dress, work and worship that have persisted across time.

CRITICS PICKS: What to see, hear, taste and more this weekend

His pictures are straightforward but invested with quotidian drama. A 1955 image of a woman planting rice, from his series on fishing and farming communities, has particularly concise power. Cropped at the shoulders and sheathed in wet earth, her body appears as the agent and the echo of the seedling in her hand.

For all of Hamaya’s gravitation to the harmonious ways of the past, one of his most enduring bodies of work documented an episode of intense immediacy and violence. Massive civil unrest erupted in Japan in 1960 upon the renewal of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, which extended American military presence there.

One of Hamaya’s photographs, edge to edge with demonstrators, distills the conflict neatly along the diagonal. Filling the lower wedge are police forces, defined by the repetitive pattern of their hats, anonymous uniform circles. Confronting them from the upper corner are outraged citizens, distinct, individual faces gaining strength in unity.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

After publishing his “Chronicle of Grief and Anger,” Hamaya pursued tamer journalistic work for the photo agency Magnum. A gallery of unremarkable pictures of spectacular landscapes from the ‘60s and ‘70s brings his section of the exhibition to a dilute close.

Yamamoto began as a poet and continued to write and publish throughout his life. Deeply influenced by Surrealism, his photo collages, combination prints and staged photographs are fueled by intense subjectivity. Surrealist poems in visual form, they mine the inner world of the perceiver and the act of perception itself.

He had a keen eye for uncanny textures and surprising disjunctions found in the everyday, but mostly staged his own incongruities in-camera or in the darkroom: a gowned woman with a sailboat for a head; a female nude spiked with bolts and screws; a chair with human legs; a foot with shrimp for toes. Among his most potent pictures are self-portraits that vivify notions of sight as an internal, psychic, erotic and charged process. In one, from 1940, Yamamoto holds a glass eye in front of his own, a blind surrogate blocking the real seer.

PHOTOS: Best art museum exhibits of 2012 | Christopher Knight

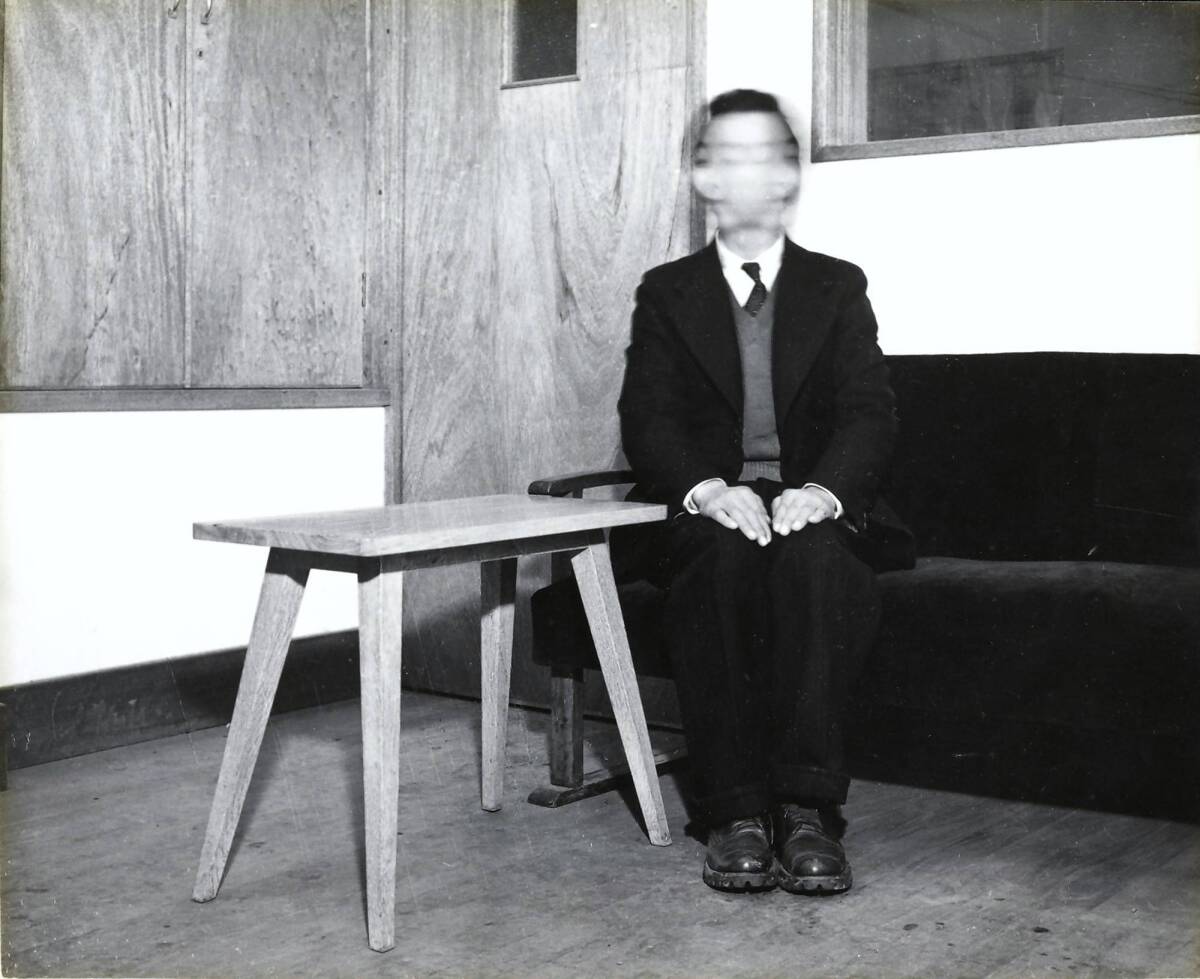

Yamamoto wrote in his diary that art “comes out of some disobedient spirit,” and for his aesthetically subversive views, he was monitored and interrogated in the late ‘30s by an official force known as the Thought Police.

For all of the French influence on Yamamoto’s work, the at-times overbearing presence of Man Ray and Magritte, this biographical detail (from the show’s informative catalog) grounds the work in its specific place and gives added resonance to its recurring motifs of confinement — bird cages, barred windows and ropes.

“Japan’s Modern Divide” reads, ultimately, as a study in contrasting attitudes toward time and reality, with Hamaya operating in the concrete realm of tradition and action, and Yamamoto striving to convey the emergent, what lies beneath and within the pulsing present. Hamaya’s work is wakeful reality to Yamamoto’s dissonant dream, his photographs prose-like answers to Yamamoto’s elusive questions.

MORE

TONYS 2013: Nominees, photos and full coverage of the awards

CHEAT SHEET: Spring Arts Preview

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.