Column: Mark Bradford brings ‘dexterity of De Kooning’ and a commitment to activism to 2017 Venice Biennale

- Share via

It’s been more than 10 years since a painter has represented the United States at the Venice Biennale. That was Ed Ruscha in 2005. This week, the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University announced that another Los Angeles painter, Mark Bradford, would be given free rein at the U.S. Pavilion for 2017’s Venice Biennale.

It’s too soon for Bradford to divulge details about what he has in mind for his Venice installation, but we can be sure that it will be more than simply pretty paintings hanging on walls. There will be a message.

The artist’s international reputation rests on deeply layered canvases that take on issues of class, culture, race and gender in abstract ways. He also helped launch a social services organization and gallery space in Leimert Park called Art + Practice, devoted in part to helping foster youth.

This attention to politics and activism, along with Bradford’s formidable painting skills, are why Rose director Christopher Bedford says Bradford is the right artist right now to represent the U.S. at one of the most high-profile contemporary art events in the world.

“I don’t know if we’ve seen someone with the dexterity of [Abstract Expressionist Willem] De Kooning who is also committed to activism,” Bedford says. “That is unique to art.”

Bedford sounded ebullient as he discussed the news over the telephone on Wednesday morning. “I have two hats of loyalty here,” he says. “First and foremost to Mark. I want this to be his moment in the sun. But there is a secondary story: I want people to think about the Rose.”

That the Rose Art Museum, which just half a dozen years ago was in danger of having its collection sold off to make up for recession shortfalls, is the sponsoring institution is an unprecedented comeback of a nearly shuttered museum.

Certainly, Bradford’s selection is momentous on its own. He is only the third African American artist to represent the U.S. at the Biennale in a solo capacity. (The other two were Robert Colescott in 1997 and Fred Wilson in 2003.)

And as the first painter to take over the vaunted U.S. pavilion in a dozen years — following a series of artists working in installation, performance and video — his choice proves once again that painting isn’t dead, nor does it even have a passing fever.

“At this point, painting is like a vampire,” jokes Bradford on the telephone. “It’s been resurrected so many times.”

Certainly, in his hands it has come alive in singular ways. Bradford’s stormy abstract compositions are comprised of layers of paint and detritus (from street signs to perm papers) that comment on societal issues in sly and beguiling ways.

“I’ve always been interested in art history, the history of painting, reanimating, expanding that history,” says the artist. “It’s always been central to my work.”

Bedford says it makes sense that the two most recent painters to represent the U.S. at the Biennale would hail from L.A.

“I think you can divide the art world in the United States roughly as follows,” he explains. “The center for academic art history is Boston. The commercial art world is in New York. And the center for art schools is Los Angeles. So the idea that great painters would emerge from that context shouldn’t surprise anyone.”

And, in fact, it was Bradford’s dexterity as a painter that captivated Bedford to begin with.

The pair have known each other for roughly a decade.

They first met in the mid-2000s, when Bedford was an assistant curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and he paid the artist a studio visit, then included him in the 2008 group exhibition “Hard Targets.”

Two years later, after Bedford had gone to work at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Ohio, he helped organized a traveling exhibition of the artist’s work that was shown at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston and San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, among other institutions. (L.A. missed the boat.)

But it was a 2014 exhibition of Bradford’s paintings and sculptures at the Rose, titled “Sea Monsters,” that made Bedford think the time was right to aim for something even bigger.

“That was a really fantastic show,” he says. “The idea that Mark might represent the U.S. in Venice hit me when I saw those sublime paintings of his.”

In his review of the exhibition, Boston Globe critic Sebastian Smee described them as “a bold, body-shaking suite of paintings and sculptures.”

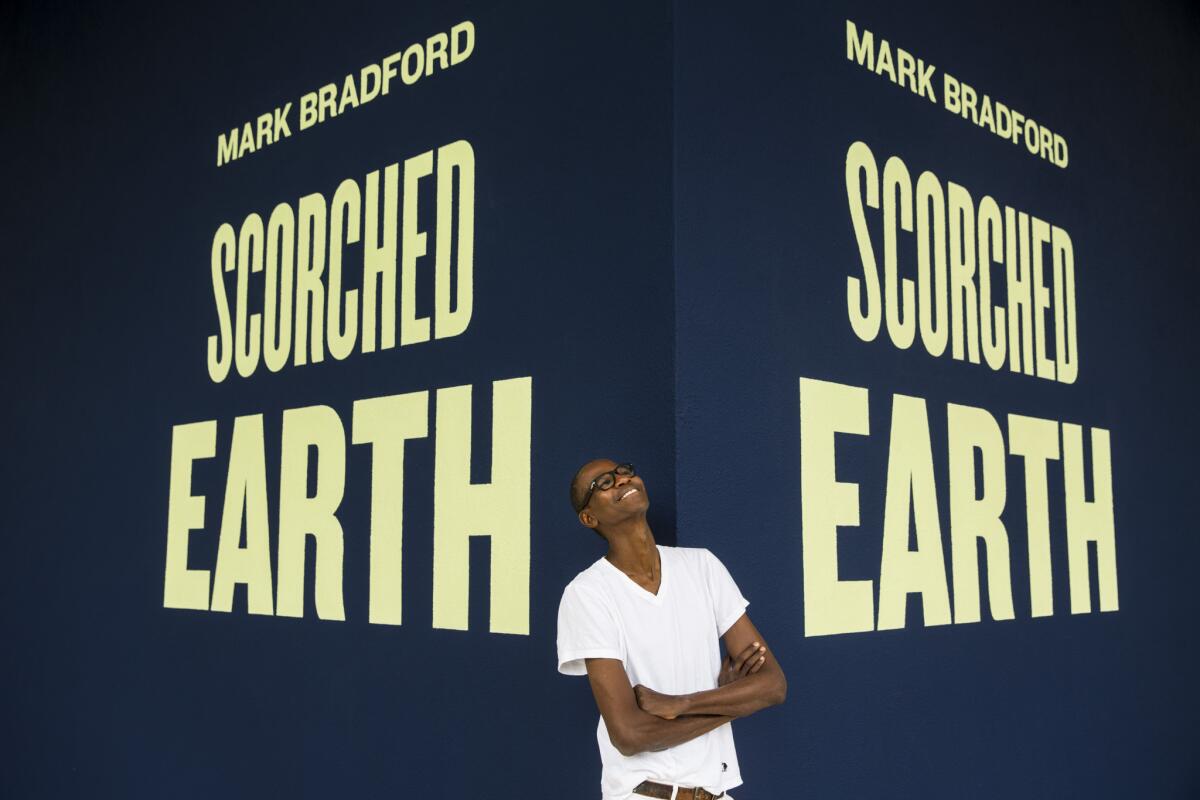

Mark Bradford in front of a sign for his solo show, “Scorched Earth,” at the Hammer Museum in the summer of 2015.

This ethos is something that fits well with the history of the Rose Art Museum and its academic setting, Brandeis University. The museum was established in 1961 with a social justice mission.

But following the economic collapse of 2008, the university pursued the idea of disbanding the museum and selling off its collection — priceless works by artists such as Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol. Or as Bedford puts it, “The greatest collection of Modern and contemporary art associated with any university in the country. ... The idea that that story would dissolve is unthinkable.”

An outpouring of support (as well as a lawsuit filed by museum supporters) led the university to scuttle the plan.

In the intervening years, the little university museum that was almost scavenged for parts has come roaring back.

Bedford joined as director in 2012. Bradford joined the museum’s board about two years ago, at Bedford’s urging. But he says that he was most inspired by the university’s commitment to social issues.

“The idea of social justice permeates every single department of the school,” he explains. “Social practice wasn’t just a department in the school, it was in every single area of the school.”

Now the museum — and one of the artists who has participated in its revival — are going to Venice as representatives of the United States.

Good news for Los Angeles. Even better news for the Rose.

Staff writer Jessica Gelt contributed to this story.

Twitter: @cmonstah

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.