Why the Rauschenberg Foundation’s easing of copyright restrictions is good for art and journalism

- Share via

Last week, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in New York announced that it would ease copyright restrictions on art belonging to the artist. The move will make images of Rauschenberg’s work — he was a groundbreaking figure known for his hybrid assemblage-paintings — much easier to access and disseminate.

It will do this in a number of ways. One, the foundation has issued a statement that provides guidelines for fair use of its imagery, and imagery of Rauschenberg’s work in general, making it simpler for museums and members of the media to employ images.

Second, the foundation will even allow royalty-free use of its images to museums and educational institutions who might want to use Rauschenberg’s art in promotional materials — something that is not governed by fair use.

This is good news — not only for reporters and for institutions, but also for the free flow of ideas.

“The people who are the best stewards are the scholars and the museums,” says foundation CEO Christy MacLear. “Professors were making choices of images and teaching based on what images are available. That affects our history. What you teach should be the best pieces, not the free pieces.”

It is too early to tell whether other foundations or artists’ estates will follow Rauschenberg’s lead. For one, there’s the issue of money. The Rauschenberg Foundation is well capitalized and therefore is able to walk away from the image-rights income it would otherwise earn (about $100,000 per year).

“Rights fees are an important way for some smaller estates to go about doing what they’re doing,” says Robert Panzer, executive director at VAGA, an image-rights clearinghouse in New York City that represents Rauschenberg’s work, as well as others’. “There are practical considerations.”

In addition, fair-use laws (explained here) already allow for the reproduction of works in the news media and critical journals under some circumstances — on the grounds that they provide new insights and analysis and, therefore, they aren’t copying for the sake of copying.

Professors were making choices of images and teaching based on what images are available. That affects our history.

— Christy MacLear, CEO of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

“In reality, almost everything the foundation claims to be innovating is already a practice that ARS largely goes by,” stated Theodore Feder, president of the Artists Rights Society, another rights clearing house, via email. “For instance, we too recognize the fair use exemptions for editorial commentary, criticism, news reporting and non-commercial scholarship.”

That is indeed true. Fair-use laws already technically protect the publication of images in relation to criticism and news stories. But the day-to-day on this is more complicated than saying, “Hey, this is fair use.”

Part of this is because navigating copyright is downright labyrinthine. Even if a work is held by a museum, it is often someone else — most frequently the artist or the artist’s estate — who retains copyright to the work (for their lifetime plus 70 years). And their copyright governs all reproductions of a work, which would therefore include any and all pictures.

So even if I have my own totally rad picture of a Jeff Koons balloon dog sculpture, the right to reproduce it lies with the artist or whatever entity he invests with that right (such as VAGA or ARS).

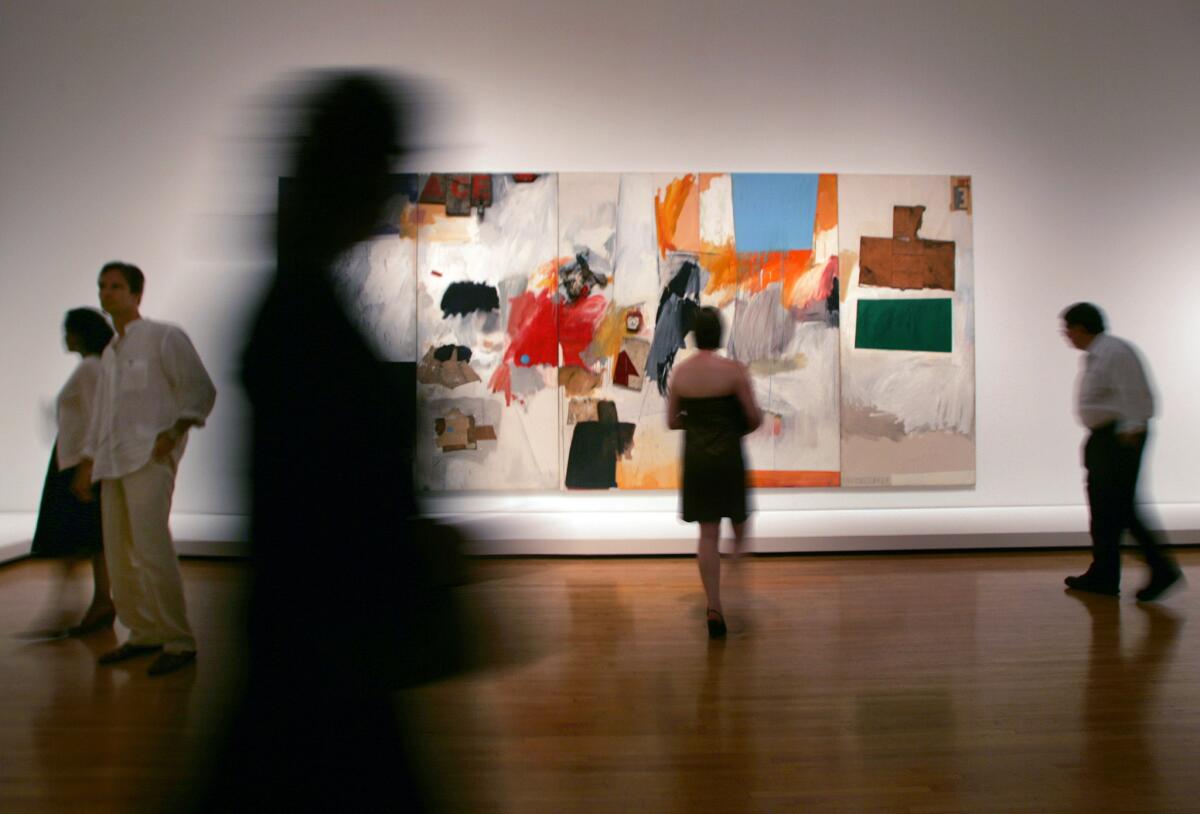

Visitors make their way past Robert Rauschenberg’s “Ace,” from 1962, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in 2006.

Moreover, the boundaries of fair use can be fuzzy. And while I would likely be covered by fair-use laws in publishing my balloon dog photo alongside my withering analysis of Koons’ work, it’s not the sort of thing I’d want to have to defend in court — which would be costly and time-consuming.

Frankly, in our sue-happy age, the idea of publishing any photo without clearances (even one I take) is the sort of thing that would give me and my bosses nuclear levels of agita. So I always work to get clearances — be it permission to shoot or by securing handout photos that have been cleared in advance. If you publish an art blog once or twice daily, however, this is a process that can quickly get onerous. (Especially if you’re trying to clear something after 3 p.m. Pacific, when New York is at happy hour.)

By proactively stating its policies on fair use, and by easing restrictions on other uses, the Rauschenberg Foundation offers scholars and arts journalists the comfort of knowing that we’re not going to be sued for publishing a picture of his angora goat combine in some deep-dive story about artists and stuffed goats. And it means that any pictures of Rauschenberg’s work in the L.A. Times archive can resurface on occasion without piles of legal back and forth.

All of this is not to say that copyright protection isn’t important — especially when it comes to commercial uses.

Copyright is also the right to say no, to say I don’t want that on a toilet paper roll.

— Robert Panzer, executive director, VAGA

“If you go on the Internet and type in the names of any of our artists, you will see thousands of illegal reproductions,” says Panzer, whose organization also represents painter Jasper Johns and collagist Romare Bearden. “Many of those are minor. But there are very commercial things. You’ll see posters from companies you’ve never heard of. Often, they will shoot images out of books or simply copy other posters. What they are doing is selling infringed art.”

Feder concurs. “The unauthorized and unbridled use of artists’ work is a growing concern,” he says. “Artists, their estates and foundation must make sure that the patrimony over which they have charge is distributed in a way which reflects credit on the artist.”

Photographers have been especially hard hit by cut-and-paste Internet culture because they often survive by licensing reproductions of their work.

“Copyright is also the right to say no,” says Panzer, “to say I don’t want that on a toilet paper roll.”

I recognize the importance of artists being able to protect their work. Being a writer, I am no fan of being ripped off.

But the Rauschenberg Foundation’s announcement is the sort of thing that makes my job a little easier: being able to share and talk about art, choosing images not because they have been cleared, but because they illustrate a story.

“It’s about redefining control,” says MacLear. “We just want to make sure the best images are out there and people want to use them.”

“[The artist] Rachel Harrison recently called us up,” she adds. “She wanted to use some of [Rauschenberg’s] images. She was so surprised that we not only said yes, but that we didn’t give constraints. She could crop and whatnot. But that’s what Rauschenberg’s work was about.”

Let’s hope other artists and artist estates feel the same way. Art draws from the culture around it. It’d be nice if occasionally the culture could more easily draw back.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.