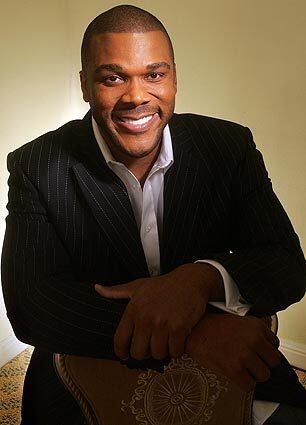

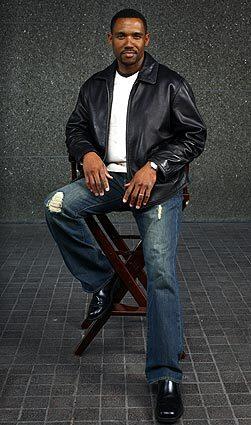

Tyler Perry, photographed in 2006, says that when it comes to traditional Hollywood, “I still don’t know the code and how it works, when to be quiet and when to speak up. And that is OK.”

Tyler Perry, shown in 2006, has become the most powerful black filmmaker in movies today with his string of films that mix comedy and romance with religious and urban melodrama. His Meet the Browns, which opened to $20 million on Easter weekend 2008, is the latest of his five films. He has total creative control over his projects. (SPENCER WEINER / Los Angeles Times)

Filmmaker Ava Duvernay, who won acclaim for the single-mother story Saturday Night Life and a hip-hop club documentary, This Is the Life, says she has met with resistance while pitching a romantic drama called The Middle of Nowhere, about a woman whose life is upended when her husband is imprisoned. (JAY L. CLENDENIN / Los Angeles Times)

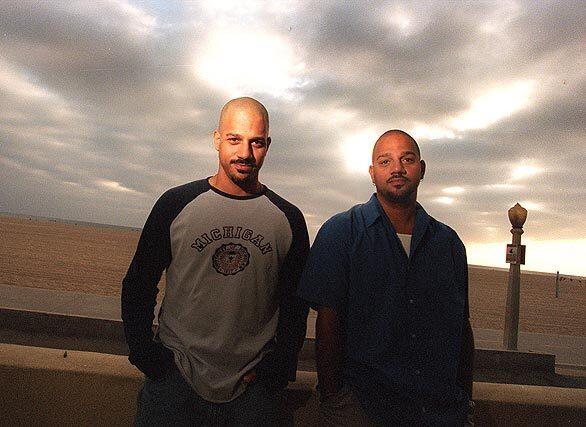

The success of Perry’s formula has proven formidable for some black filmmakers. We want to tell multidimensional stories with in-depth characters, said DAngela Steed, right, who is one of the heads of Strange Fruit Media (which produces films and television series) and recently pitched a made-for-TV drama to a cable network. Its response? Whats the Tyler Perry version? Nia Hill, left, Steeds partner, added that the situation extends beyond just a lack of opportunity. The images that are being put forth are too powerful to be taken lightly. (Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

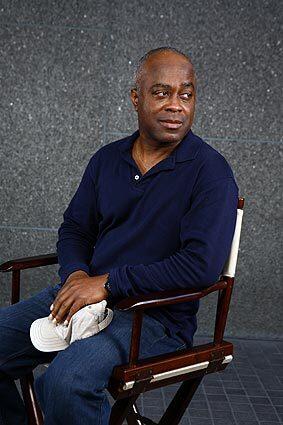

Winning support for serious subject matter from black audiences poses an ongoing problem, says Charles Burnett, director of the 1977 portrait of a working-class Watts neighborhood, Killer of Sheep.” Trying to get black people to go see The Great Debaters was like pulling teeth, said Burnett, who is seeking distribution for his latest film, Namibia: The Struggle for Liberation, about the long battle struggle waged by the African country for independence. Our own people dont support stories that make a difference, stories that support the independent spirit. (JAY L. CLENDENIN / Los Angeles Times)

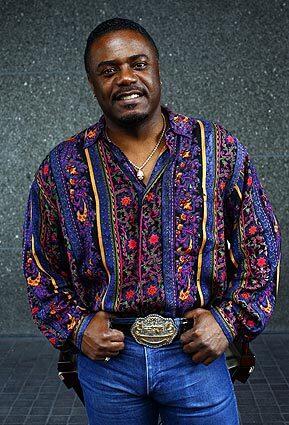

The indie scene has proven especially tough for black filmmakers to crack. Actor Reginald T. Dorsey, who is seeking distribution for Kings of the Evening, a drama set in the Great Depression that he helped produce, said studios and backers often tell him that the financial risks in investing in projects without a high concept or a major star attached outweigh the benefits, and that there is little international interest in small black films. Its like a slap in the face, he said. My movie is more than just a black film. Its about where youre from and what you know. (JAY L. CLENDENIN / Los Angeles Times)

When it comes to Hollywood, theres been all this hemming and hawing, says Caran Hartsfield, who has been working to get financing and distribution for her comedic drama Bury Me Standing,” about four family members and their differing reactions to the death of a relative. “Theyll say, Oh, we love the script, but it makes people nervous because its a black drama. It doesnt fit within the formula. (CAROLYN COLE / Los Angeles Times)

Not all filmmakers are feeling stifled in the current climate. Kent Faulcon, an actor who has written and directed a thriller about a small-town teacher and a hit man called Sisters Keeper, says, I feel that theres room for me and those who are bringing something new. The response Ive gotten has been overwhelming. Im not discouraged. I feel enthused theres a hunger there. (Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Black filmmakers gather to discuss their successes and struggles in the film world today. From left: Kent Faulcon, Nia Hill, DAngela Steed, Charles Burnett, Reginald T. Dorsey and Ava Duvernay. (JAY L. CLENDENIN / Los Angeles Times)