Appreciation: Cinematographer Haskell Wexler was a man of vision

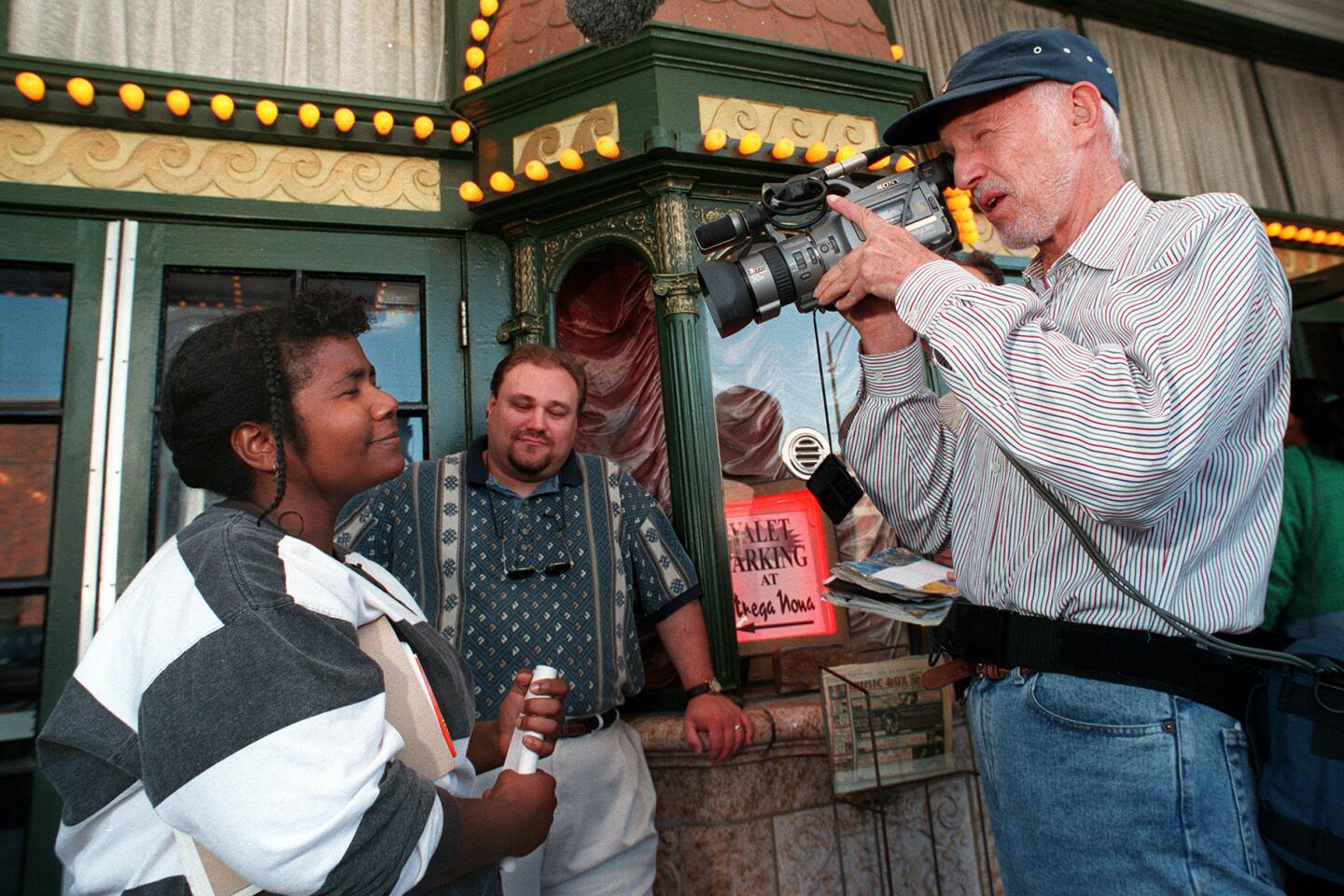

Director Haskell Wexler in Park City, Utah, at the Sundance Film Festival.

- Share via

The visual stamp of the cinematographer is still, to many viewers, a mysterious thing. But over the course of six decades, Haskell Wexler, who died last week at 93, did as much as any director of photography to revitalize the look of American movies through careful manipulation of light, shadow and perspective.

Collaborating with the aesthetically daring directors who spearheaded the New American Cinema, Wexler developed a celluloid palette to establish the nostalgic glow of “American Graffiti” (1973), the Dust Bowl desperation of “Bound for Glory” (1976) and the harsh emotional volatility of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (1966). At the same time, he pursued a separate but parallel career as a left-wing activist and maker of political documentaries.

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

Wexler made his primary mark with naturalistic films shot on location in color, but he earned his first of two Oscars for shooting Mike Nichols’ adaptation of “Virginia Woolf” in black and white on a studio set.

Rejecting the photography director’s original plan to film in color, Wexler fashioned a foreboding expressionism of oddly angled close-ups and enveloping shadows to match the stark claustrophobia of Martha and George’s house. Though the blackly comic dialogue from Edward Albee’s play is key to the film’s appeal, the atmosphere feels anything but stagy.

A vigorous, proudly arrogant personality as well as a fiery radical, Wexler clashed with several of his films’ auteurs, in part for his apparent unwillingness to respect the on-set hierarchy.

“I don’t think there’s a movie that I’ve been on that I wasn’t sure I could direct it better,” he once said. Francis Ford Coppola fired Wexler from “The Conversation” (1974), though the cameraman remains responsible for the intricate voyeurism of the opening sequence, and Milos Forman followed suit on “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975) after Wexler — taking a page from Jack Nicholson’s irreverent on-screen antihero — expressed doubts about the director’s competence.

Given his independent streak, it’s surprising that Wexler directed just one major fiction feature, 1969’s sophisticated, shape-shifting “Medium Cool.” Combining the raw immediacy of cinéma vérité with a narrative screenplay, Wexler’s movie follows a Chicago TV news cameraman (Robert Forster) who becomes increasingly disillusioned by his profession in the days leading up to the tumultuous 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Anticipating the violent upheaval on the streets of Chicago, Wexler filmed the clashes between protesters and the police and then edited the documentary footage into the narrative film. At the climax of “Medium Cool,” a National Guardsman launches tear gas directly at the camera, and an off-screen crew member shouts: “Look out, Haskell, it’s real!”

The moment is jarring, but “Medium Cool” compels us to distrust any separation between fact and fiction. The tear gas was real; the famous line was added in post-production.

Though he kept one foot in Hollywood and one foot in activism, Wexler’s technical proficiency often served his passion for social justice. If 1968 best picture winner “In the Heat of the Night” is remembered as a progressive touchstone, it’s less for the material than for Sidney Poitier’s impassioned, distinguished star turn — which received a subtle assist from the film’s cinematographer.

Sensitive to the fact that celluloid favored lighter skin tones, Wexler — who, remarkably, was colorblind — knew to light white and black actors differently.

As Mark Harris wrote in his 2008 book “Pictures at a Revolution,” “Poitier had often been the victim of thoughtless over-lighting designed for white actors that added glare to his face and rendered his expressions indistinct, but here, Wexler and [Norman] Jewison made sure that every unspoken thought that played across his lips and eyes would read on camera and be visible to moviegoers.”

Wexler’s supervision of available light helped underwrite new forms of American realism. He recognized that the New American Cinema meant not just new subjects and newly exposed bodies, but new ways of seeing.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.