Watching ‘GoodFellas’ with ‘The Wolfpack’ brothers who escaped their isolated world through movies

- Share via

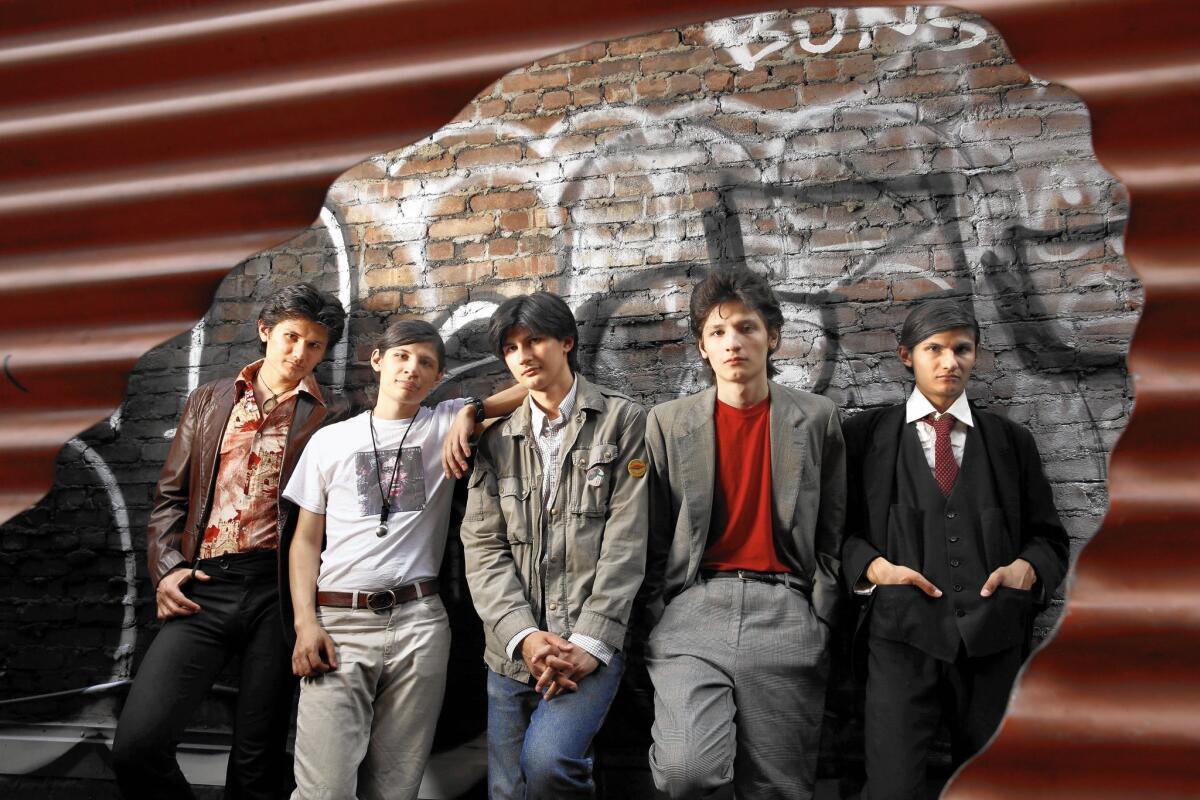

NEW YORK — Mukunda Angulo, one of the most outgoing of the six fraternal cinephiles known as the Wolfpack, looked around the stately confines of the Upper West Side’s Beacon Theater.

“This place is very ‘GoodFellas,’ ” he said.

The Wolfpack had come to the Beacon for a reunion screening of the Scorsese movie, one of the young men’s favorites.

“We’ve seen it hundreds of times, maybe more,” said Bhagavan Angulo, 23, the eldest brother, a low-key personality.

“It’s like sometimes, ‘OK, our mom is making a big Italian dinner? Let’s do “GoodFellas,” ’ “ said Mukunda, 20, the fourth-eldest.

“Doing” movies has been a longtime tradition for the Angulos, who grew up under improbable circumstances. Raised in a housing development on New York’s Lower East Side, by a rural Midwestern mother and a South American-born father who converted to Hare Krishna, they were kept away from others kids and even the neighborhood streets around them. Cinema was their lone connection to the outside world.

The Angulos’ father, Oscar Angulo, an enigmatic but domineering sort, forbade his home-schooled sons from leaving the apartment for all but the most basic necessities and took care of essentials, such as food shopping. The boys’ exposure to the wider world came by way of the film classics Oscar would encourage them to watch — older ones such as “Casablanca” and “Citizen Kane,” and the modern likes of “Pulp Fiction,” “The Dark Knight” and, yes, “GoodFellas.”

They would piece the films together on paper, then act out some or all of the scenes. Each brother would inhabit a given role that almost never varied. Sometimes they’d perform just for themselves. Sometimes they’d film their reconstructions.

In “The Wolfpack,” a documentary about the family, audiences are exposed to this colorful group through a movie that is likely to intrigue and raise questions in equal measure. Made in relative anonymity by first-time director Crystal Moselle, “The Wolfpack” arrived at the Sundance Film Festival in January and became an instant sensation, a popular audience ticket that also nabbed the Grand Jury Prize for U.S. documentary. With its captivating premise, the film also landed a deal from Magnolia Pictures.

As it reaches wider audiences, , “The Wolfpack,” which opens in Los Angeles on June 19, is sure to evoke comparisons to other documentaries featuring colorfully cloistered — if also more polarizing — real-life characters such as Big Edie and Little Edie of “Grey Gardens,” or the Friedmans of “Capturing the Friedmans.” It also shares some similarities with “Surfwise,” the 2007 documentary about the family that retreated from civilian life into a world of surfing. As it rolls out to theaters, “The Wolfpack” could confer a kind of instant cult status on a group of young men who until a few years ago had barely left their apartment, much less had a media light trained on them.

Moselle did not set out to make a movie about insularity and cinema, much less one that doubled as a social experiment. Walking down the street in downtown Manhattan about five years ago, she came across six young men, all dressed, as they were many days, in matching “Reservoir Dogs” outfits. Not long before, the boys had “broken out” — their term for their first unsupervised forays outside — and Moselle was piqued by their manner and their story.

She asked whether she could shoot them. The siblings agreed and soon Moselle was spending time with them at their apartment, often with the camera on. Moselle said it was difficult at first for her to break through.

“It was all references,” she said. “Everything felt like a film to them.” She was uncertain of where the story was going, or how to shape it into a feature.

The brothers were unsure too.

“We had spent so many years imagining ourselves in movies that it was strange to think we’d actually star in one,” said Govinda, 22, who, with his twin, is next-eldest after Bhagavan, and who possesses a wry sense of humor. As the only sibling who has moved out of the family’s apartment (he shares a place with several roommates in Brooklyn and harbors cinematographer ambitions), Govinda is the brother who’s assimilated most into the larger world. At the end of an evening with a reporter, he also handed over a business card. “I came prepared,” he said, flashing a grin.

There is something endearingly guileless about the Angulos boys, as if a baby could suddenly articulate his enthusiasm for everything new around it. At “GoodFellas,” they seemed excited by the basic ticketing and seating plan, and downright ecstatic — Mukunda in particular — about the presence of actors such as Ray Liotta in the theater. “I couldn’t believe it. Even though I’m never Henry [Liotta’s character], I’m still so excited.”

At dinner after the screening, a charge rippled across the table when the brothers learned that Joel Coen and Frances McDormand were in the restaurant. They immediately started making plans to catch the pair’s attention.

“Maybe do something daring,” said Govinda’s twin, Narayana.

“Like the orgasm scene from ‘When Harry Met Sally’?” his brother replied.

Still, the rudiments of modern life can elude them. Small talk can confound, as can restaurant ordering.

“There’s still a learning curve,” said Megan Delaney, a friend of Moselle’s who became an associate producer on the film and is both a friend to and a public attache of sorts for the brothers.

The two Angulos who are perhaps most different from the rest are the two youngest, now 18 and 16. They recently legally changed their last names from Angulo to Hughes Reisenbichler (an homage to their mother’s side of the family) and their given Krishna names from Krsna and Jagadisa to Glenn and Eddie.

If that sounds like a “Beverly Hills Cop” throwback, it should. The pair has an odd fascination with all things ‘80s, particularly Huey Lewis.

“It’s just the best music out there,” Glenn said. “I found it on YouTube. I don’t know why he’s not more famous.” One of the striking aspects of speaking to the brothers is that, since they are exposed to all manner of pop culture but largely ignorant of the relative valuations society has placed on it, they react most purely to what they like.

At dinner, the brothers explained their feelings about the documentary. They were hardly unanimous in their appreciation. Narayana is probably the most resistant; he declined a more elaborate interview about it. Govinda waved aside his twin’s concerns.

“The release is coming a long time after we broke out, and that’s the right time. Some of my brothers feel differently. But we were semi-aware that exposure was going to portray us in so many different ways, so why regret it? Why think about the negativity?”

Bhagavan, too, takes a more benign view of the newfound attention.

“It’s unexpected in a lot of ways,” said the eldest Angulo, a yoga teacher and hip-hop dancer. “But it’s all been a journey. There were times, even before the movie, when I started going out, and it was scary. I didn’t know much about the world. But over time, I learned, little by little. And now it’s like, ‘What else can I learn?’ ”

For all the ways the brothers have landed on their feet, there remain unanswered questions. Some might wonder if they really were as cut off as the movie implies; all indications, at least, suggest that they were.

More vexing is the paternal treatment. Even as the film ultimately shows some redemption for Oscar, it’s fair to ask how much his restrictive behavior went beyond tough parenting. The siblings speak of their father in opaque terms, rarely criticizing him but not defending him either; more than one used a variation of “he has his ways.”

How the siblings are doing now is also sure to be a question foremost on viewers’ minds. The answer, like so many things “Wolfpack,” can be complicated. The Angulos enjoy close relationships with one another and regularly watch movies in groups — now, perhaps more healthily, in theaters. They seem to have become much more at ease with the larger world even since Sundance.

Apart from Govinda, though, their home status continues to define them. It is a double-edged sword, giving them a support network but perhaps furthering a codependency. Govinda said he has encouraged more of them to move out.

For the moment, they are content to reap the benefits of their newfound attention.

In the restaurant, they pile on the orders and then revel in them Angulo-style; when a heaping portion of meat arrives for Govinda, Narayna, who is vegetarian, noted to his brother, “That’s an ‘American Psycho’ plate.”

Mukunda kept up the high level of enthusiasm too, even when talking about an unlikely subject.

“Did you see when we were outside before the movie? That guy with the hair?” he recounted. “We think he’s our stalker. He’s been at all of our screenings, and he always seems to be around when we’re taking photos.” Mukunda paused. “We have a stalker. I guess that’s pretty cool.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.