‘Seconds’ turns company man into Frankenstein

- Share via

Laurence Olivier was among the world’s most accomplished actors, but he wasn’t a big enough star. That was the consensus of Paramount honchos in 1965, when director John Frankenheimer was planning his eighth feature, the science fiction thriller “Seconds,” and wanted the esteemed Brit in the lead role.

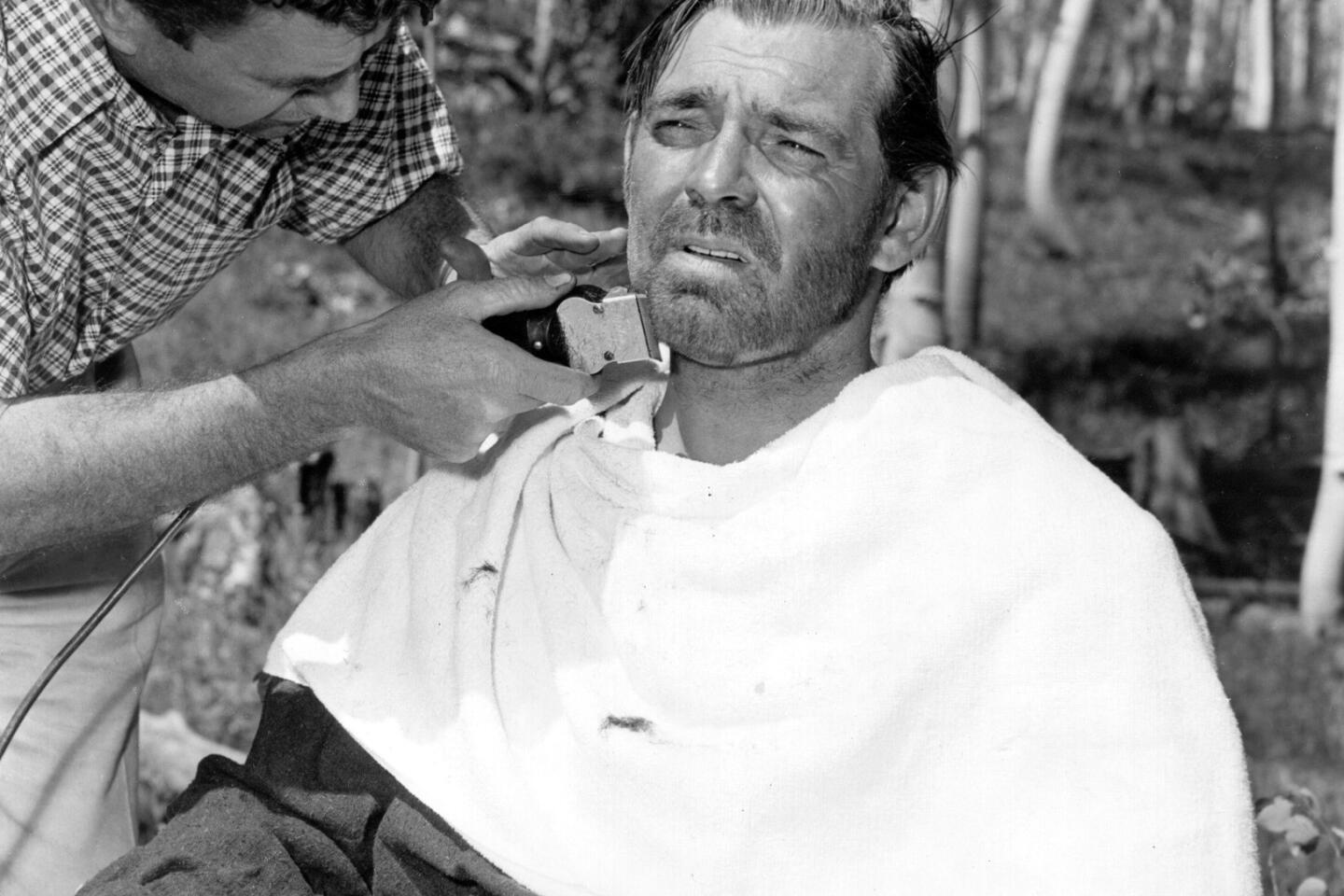

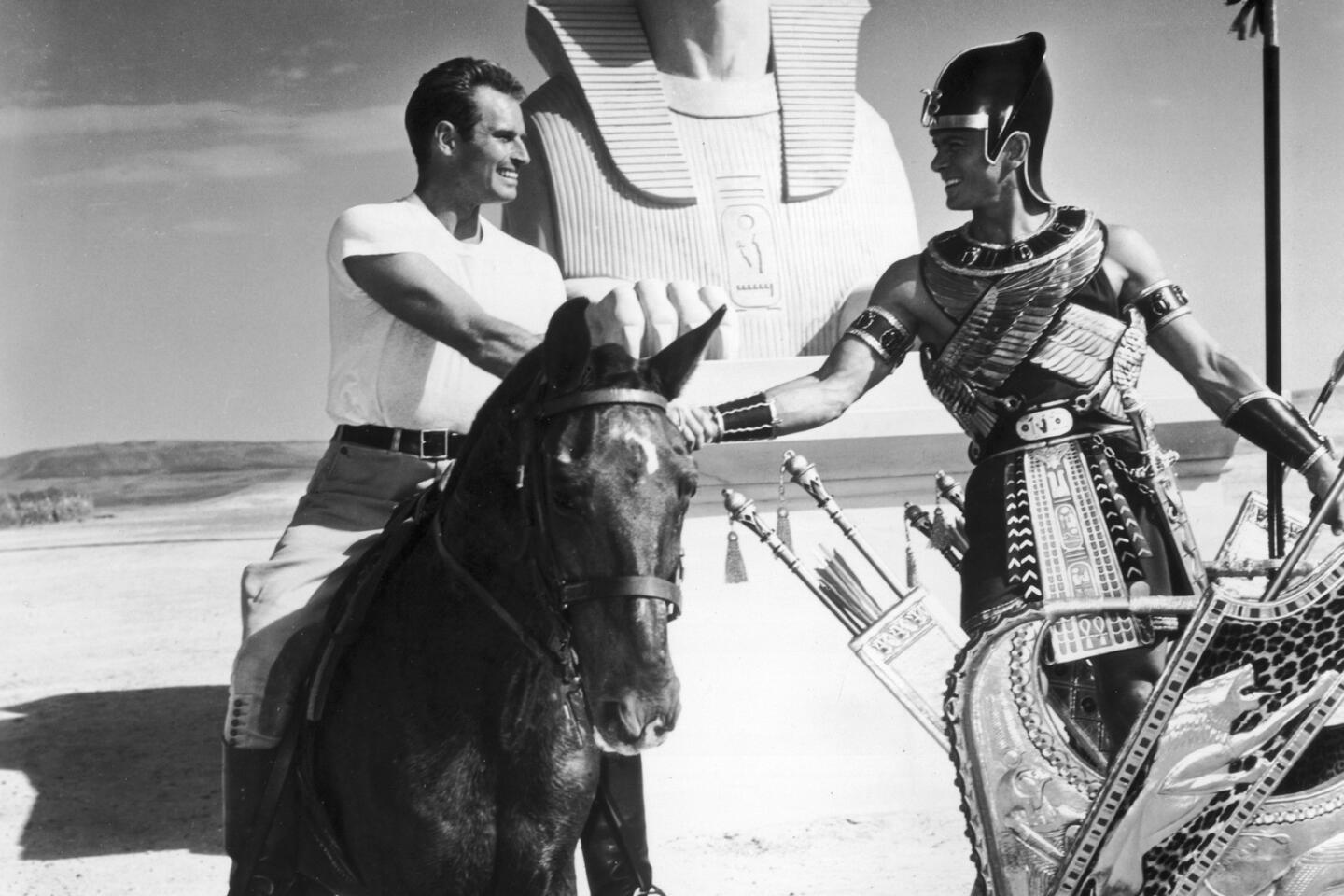

What might at first have seemed like executive-suite folly led to an inspired instance of counterintuitive casting: Rock Hudson, Hollywood’s reigning romantic-comedy dreamboat, in what is unquestionably one of the darkest studio movies ever made.

“Seconds” — available on DVD and Blu-ray on Aug. 13 in a new restoration from Criterion Collection — is an existential horror movie in which the strapping actor plays a modern-day Frankenstein monster. Whether out of an awareness of his constraints as a matinee idol or a keen sense of what would best serve the material, Hudson insisted on playing only half of that lead role. The other portion went to the prolific character actor John Randolph, in his first featured screen work.

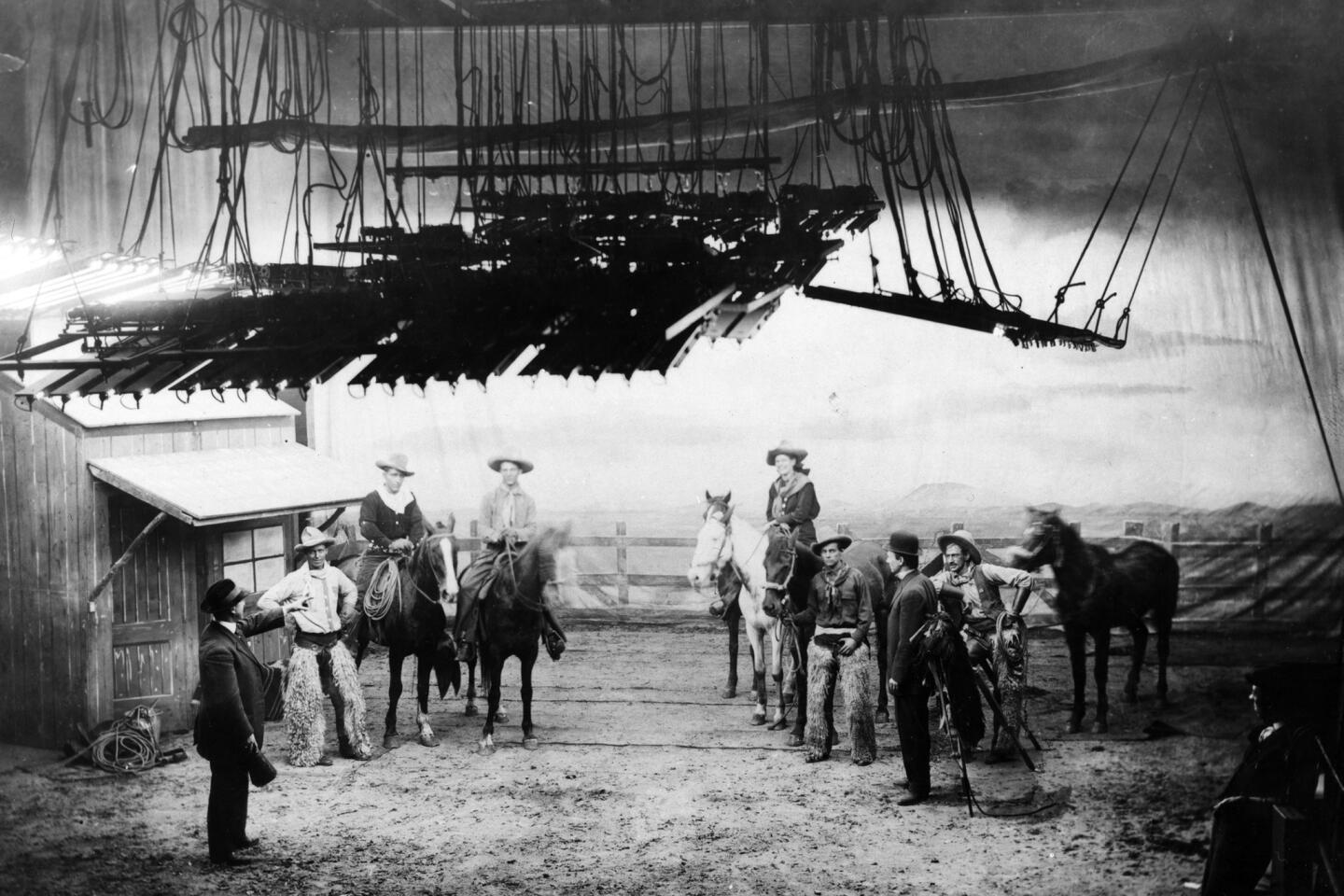

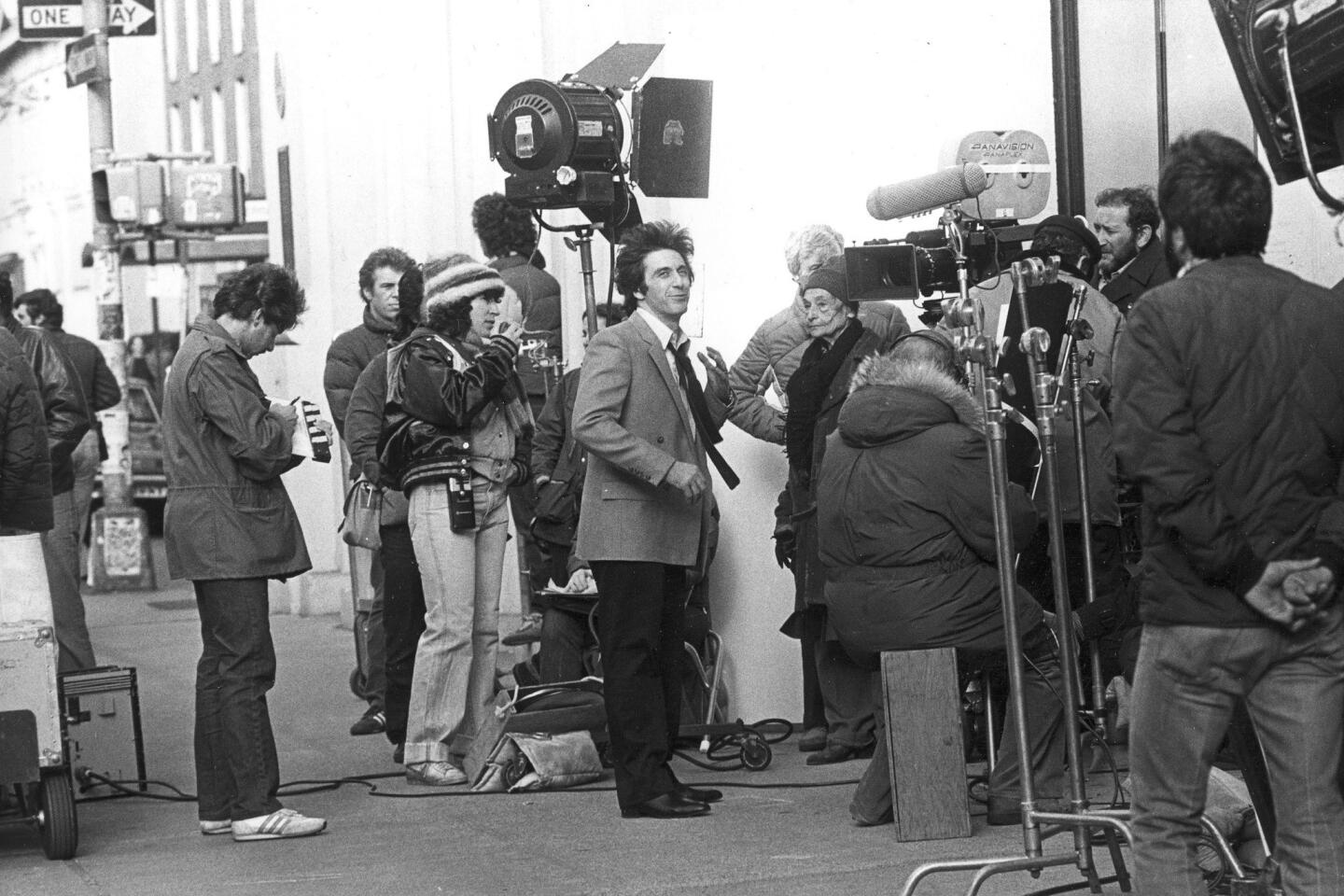

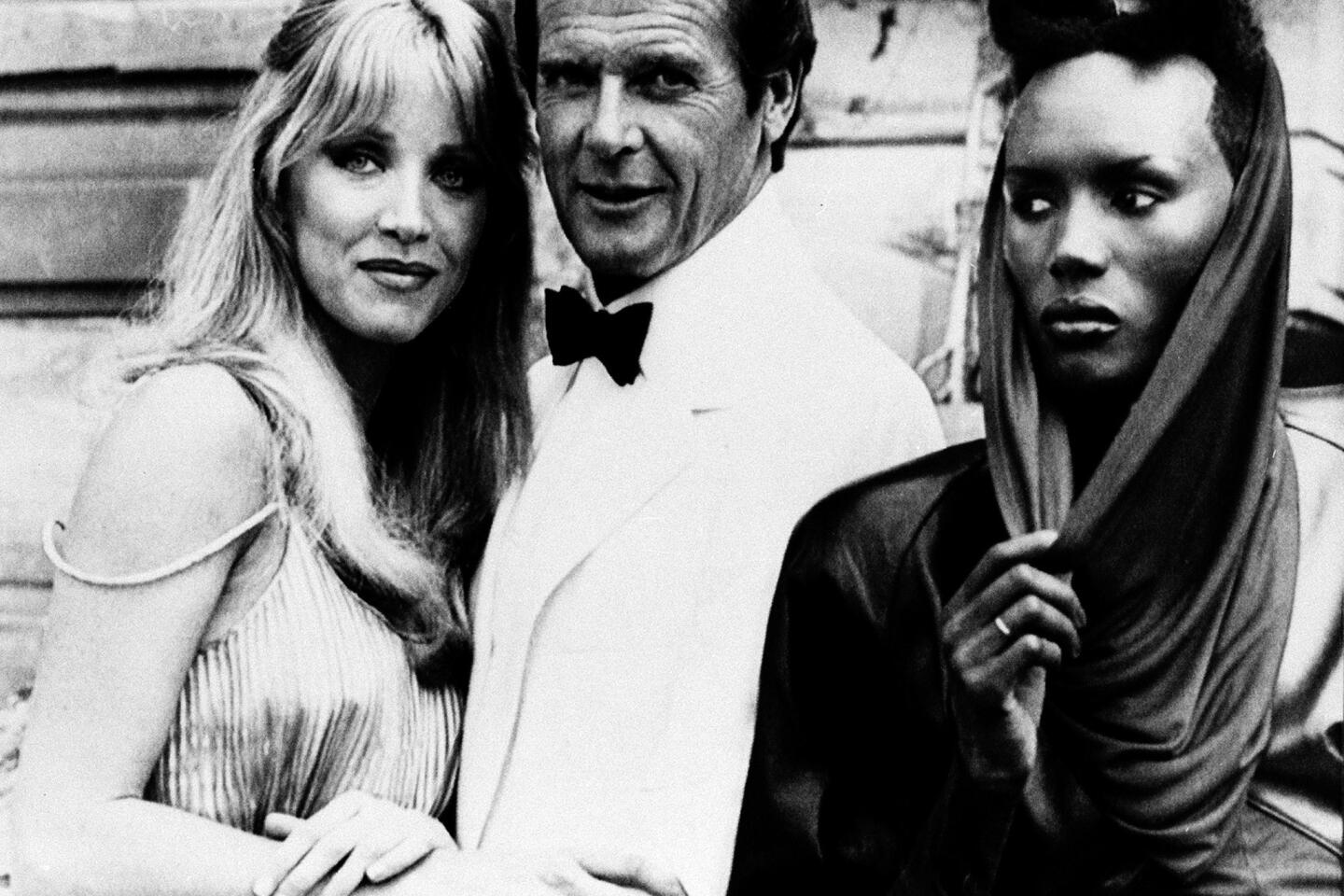

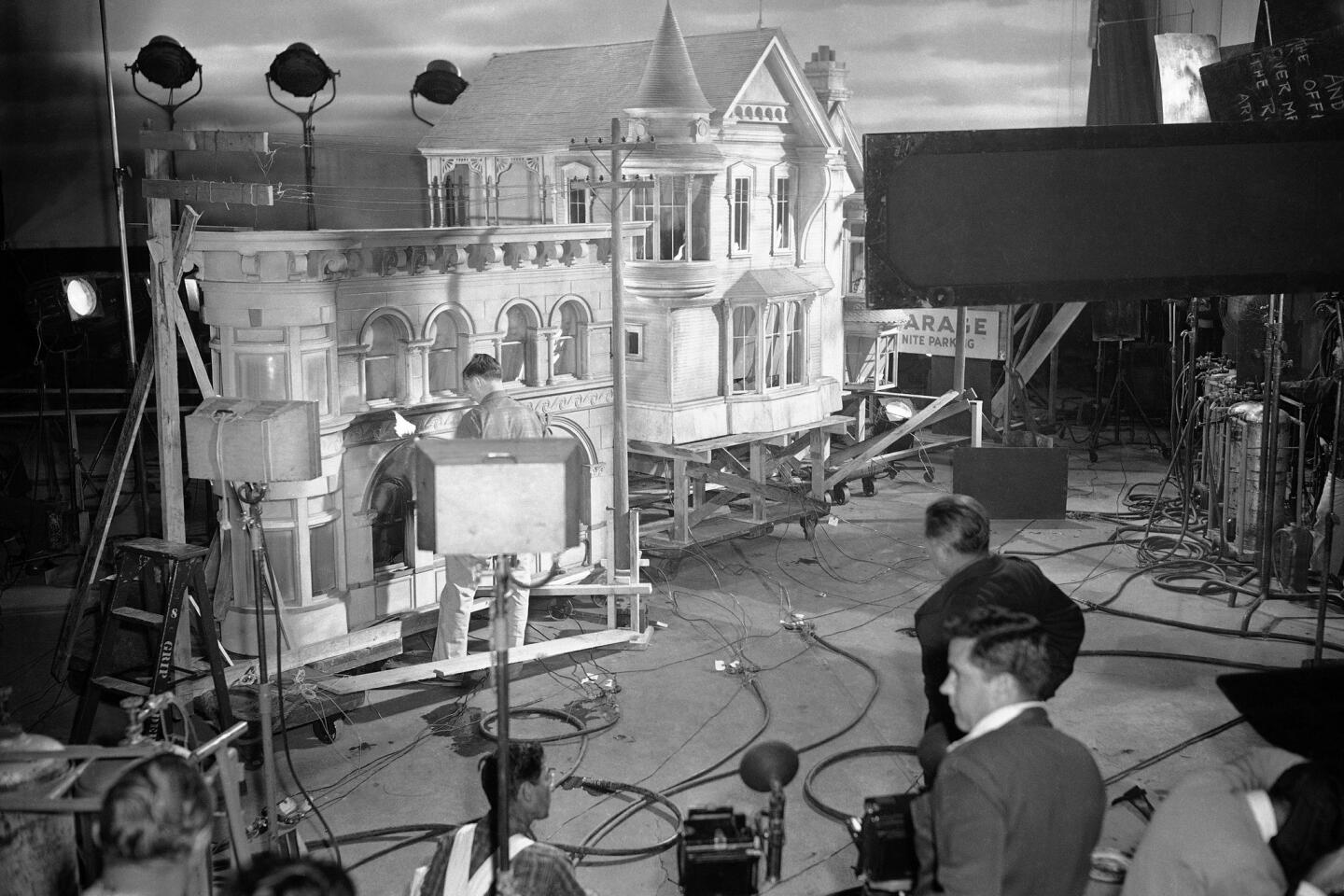

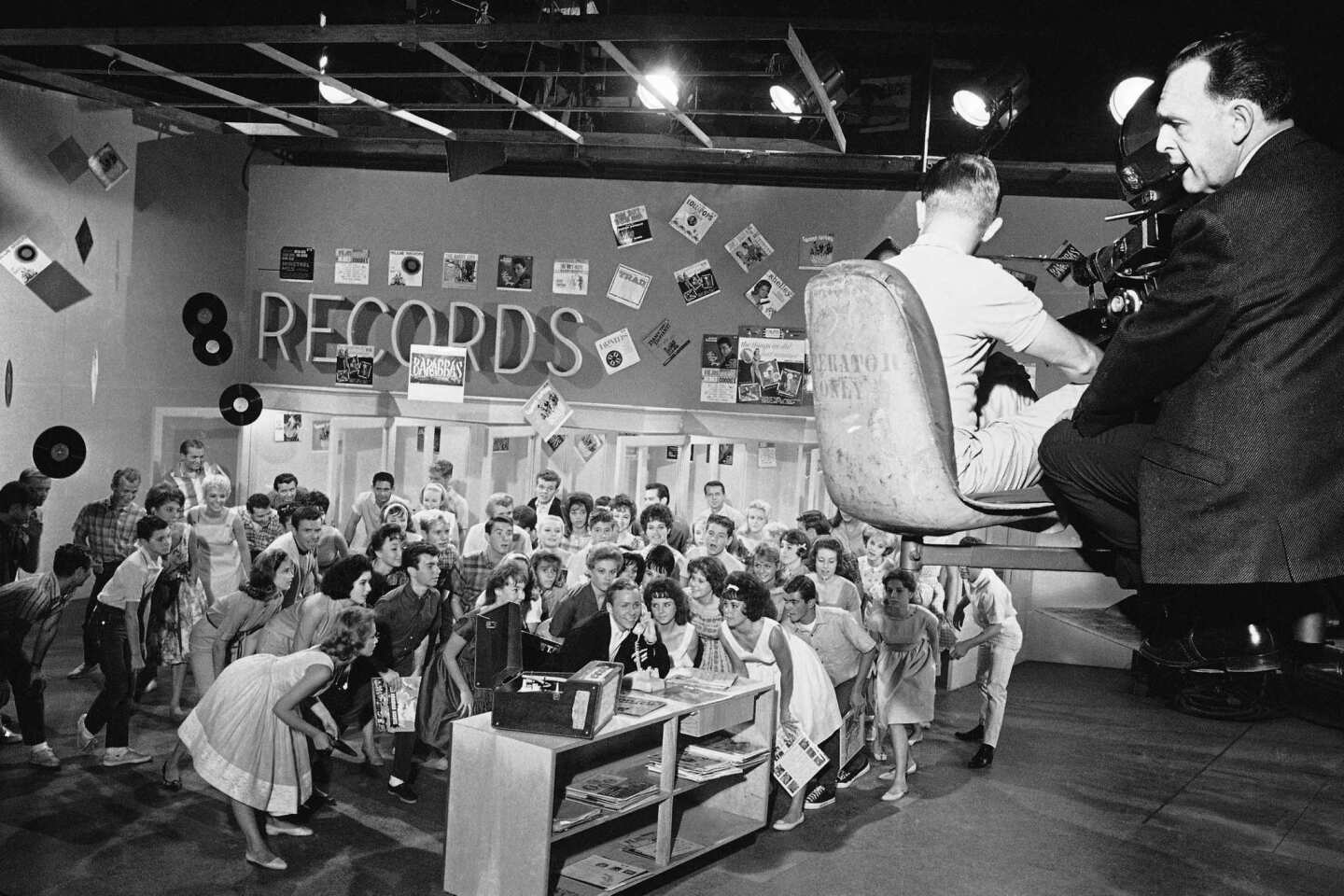

PHOTOS: Hollywood backlot moments

Hudson portrays Antiochus “Tony” Wilson, the hapless “after” in the gruesomely elaborate before-and-after scheme that propels the genre-melding story. The “before” part of the equation is Randolph’s Arthur Hamilton, a New York banker forced to peer into the abyss of his comfortable life. The pyramid scheme connecting the identities begins with a disturbing phone call and culminates in extreme plastic surgery followed by questionable psychological engineering.

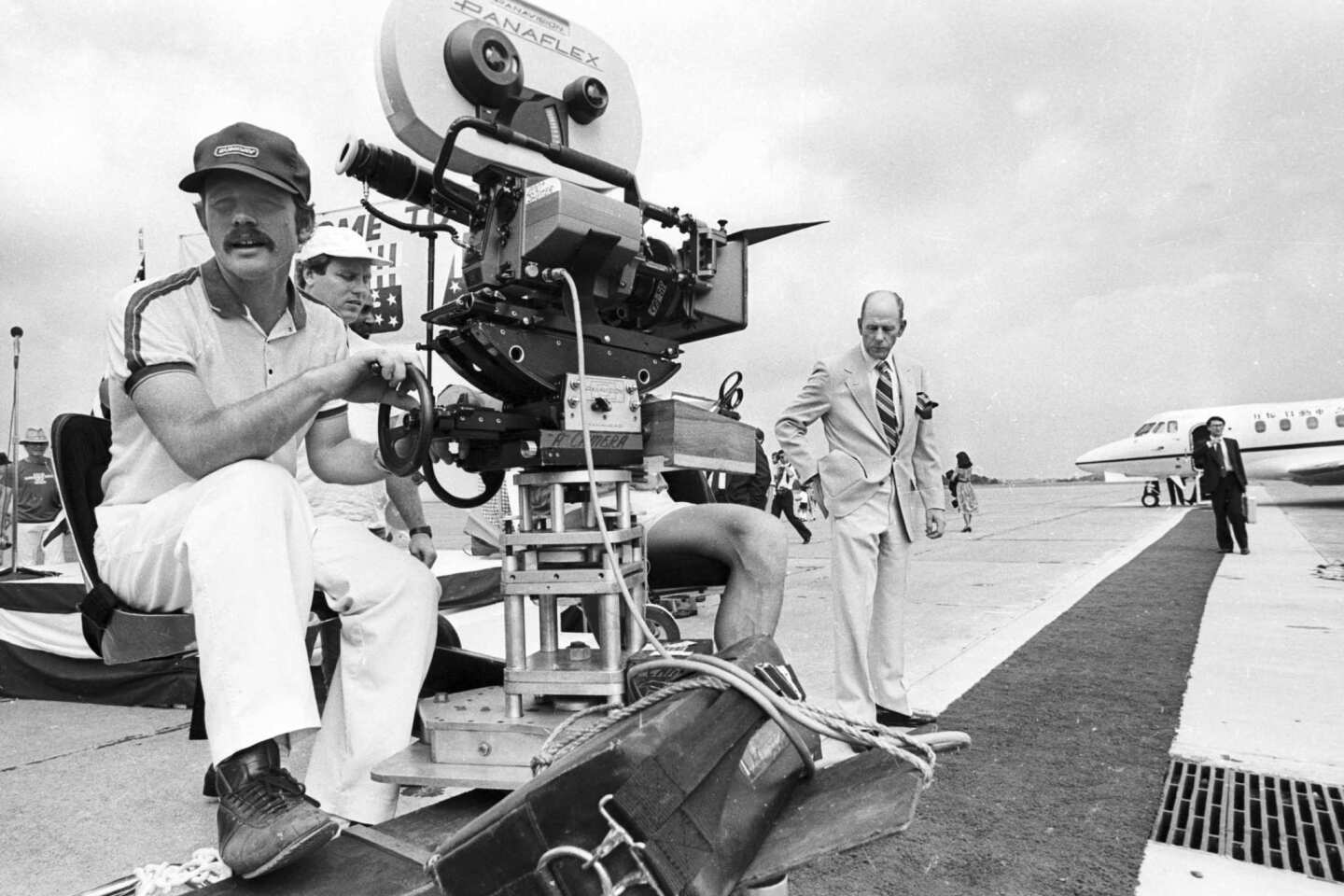

Frankenheimer, who’d cut his teeth on live TV and had the Oscar-nominated “Birdman of Alcatraz” under his belt, was a leading Hollywood director on a winning streak, commercially and critically, when he took the project’s helm. “Seconds” is the final piece in his loosely connected paranoia trilogy, which began in 1962 with the loopy “Manchurian Candidate” and continued with 1964’s Washington-cabal suspense drama “Seven Days in May.”

But the hazily defined conspiracy scenario of “Seconds” reaches far more discomforting depths than the political intrigue of the earlier films, hitting a raw nerve beneath the sheen of postwar prosperity.

Randolph’s character is one of the men in the gray flannel suits, a resident of John Cheever territory who’s beginning to recognize his own unhappiness. His resigned walk from the commuter train in Scarsdale, N.Y., to the station wagon where his wife waits behind the wheel is the perfect, heart-wrenching setup for the deep dive he’ll take into an alternate reality. (Mrs. Hamilton is played by longtime “Days of Our Lives” star Frances Reid in a rare and welcome appearance on the big screen.)

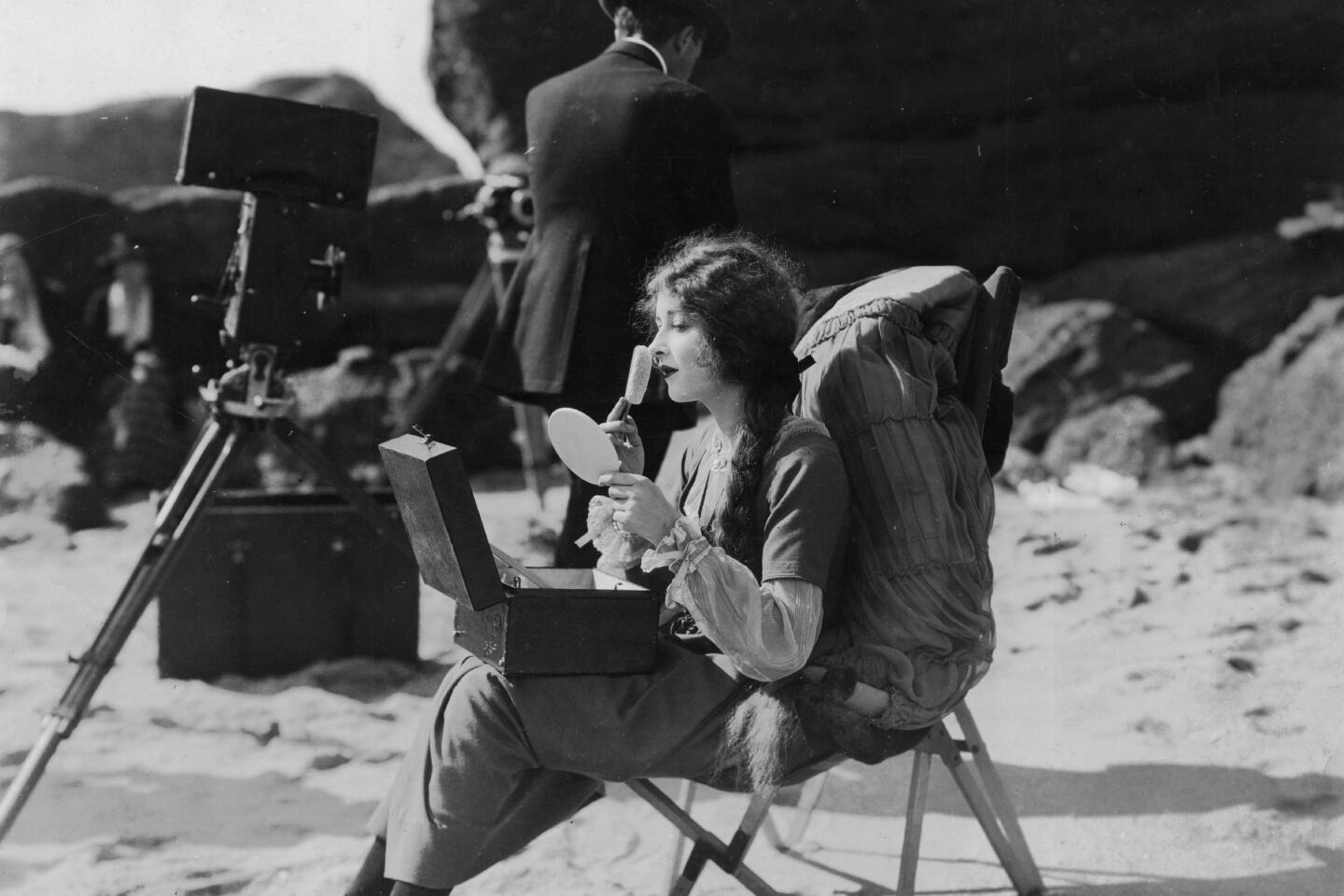

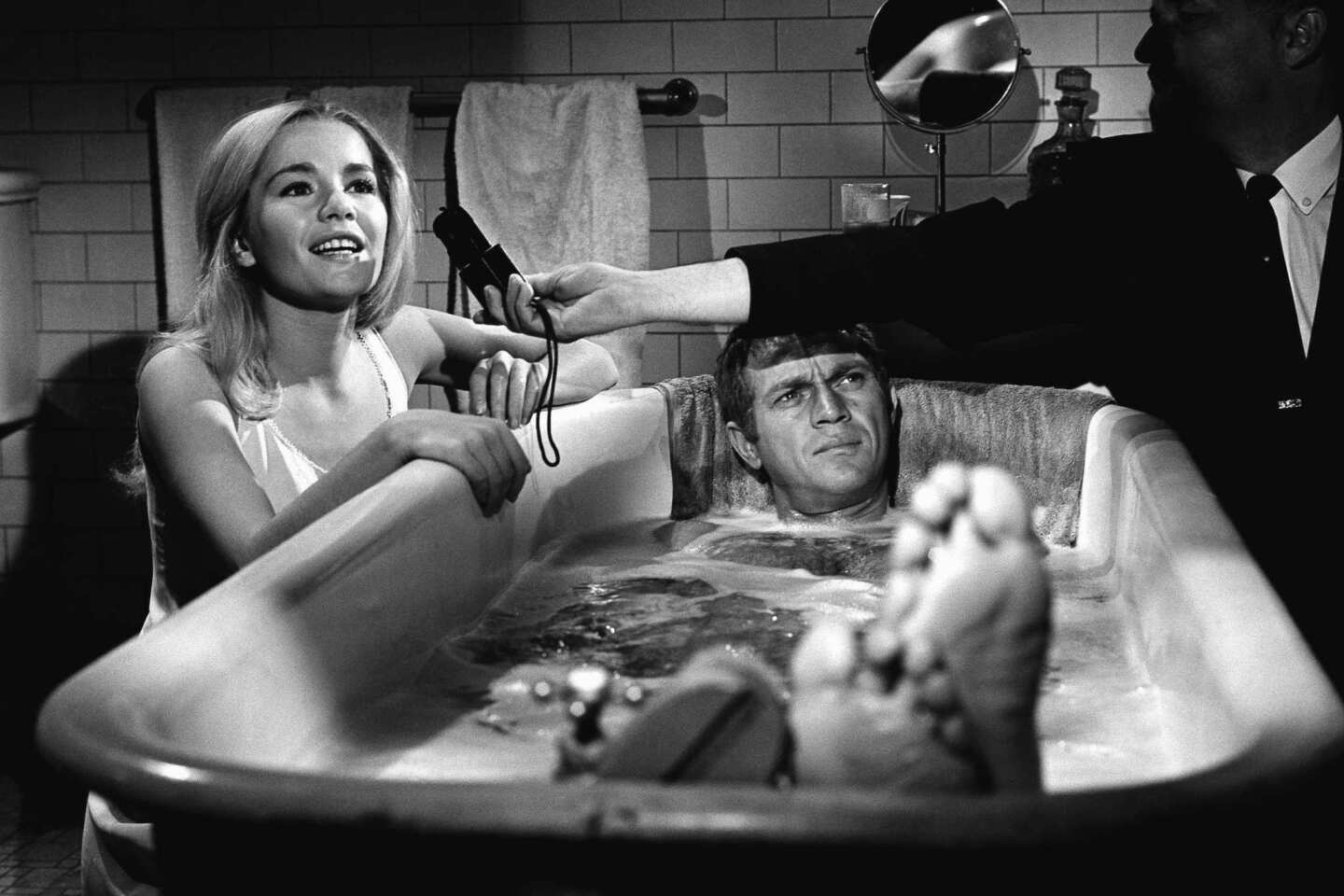

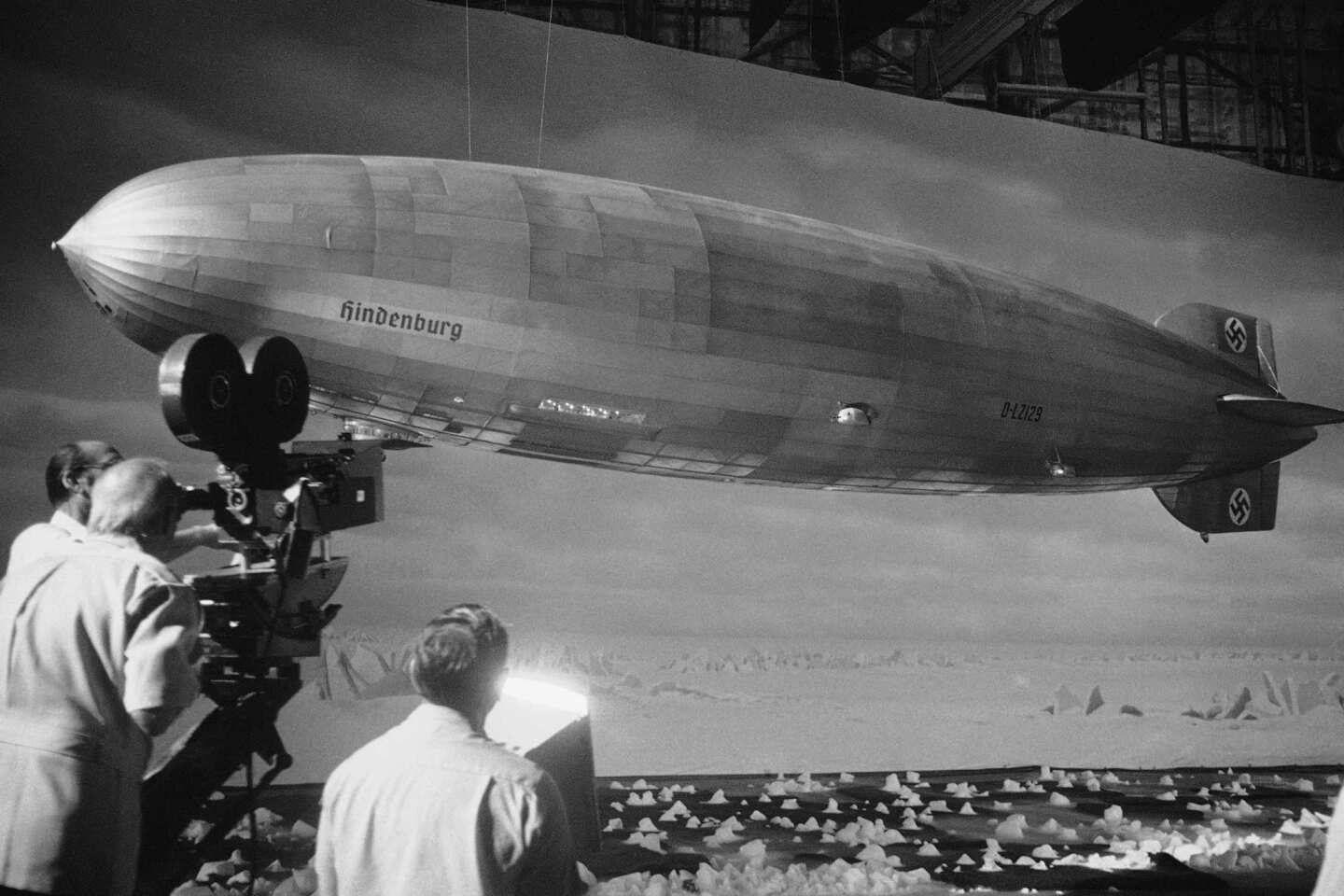

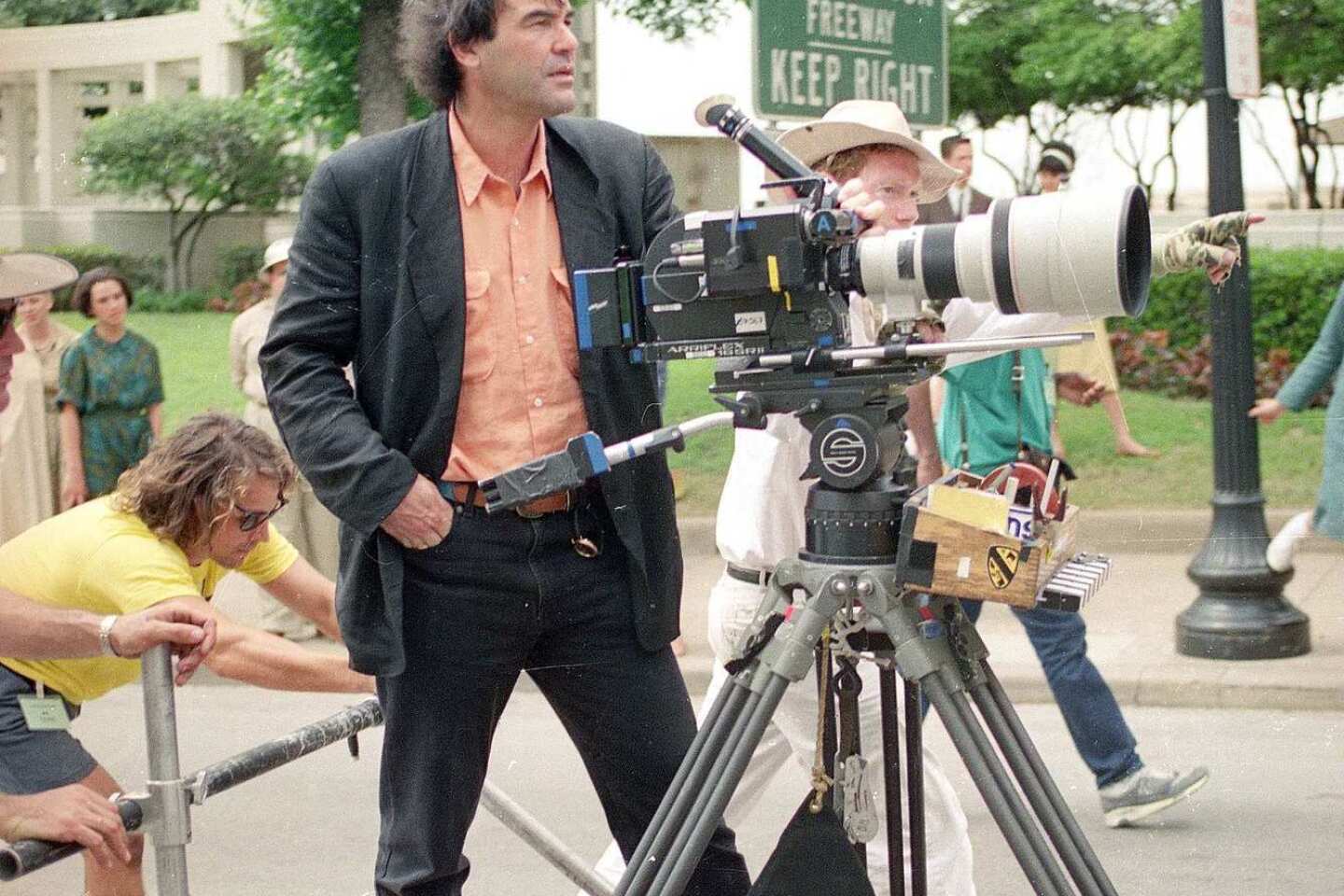

PHOTOS: Behind-the-scenes Classic Hollywood

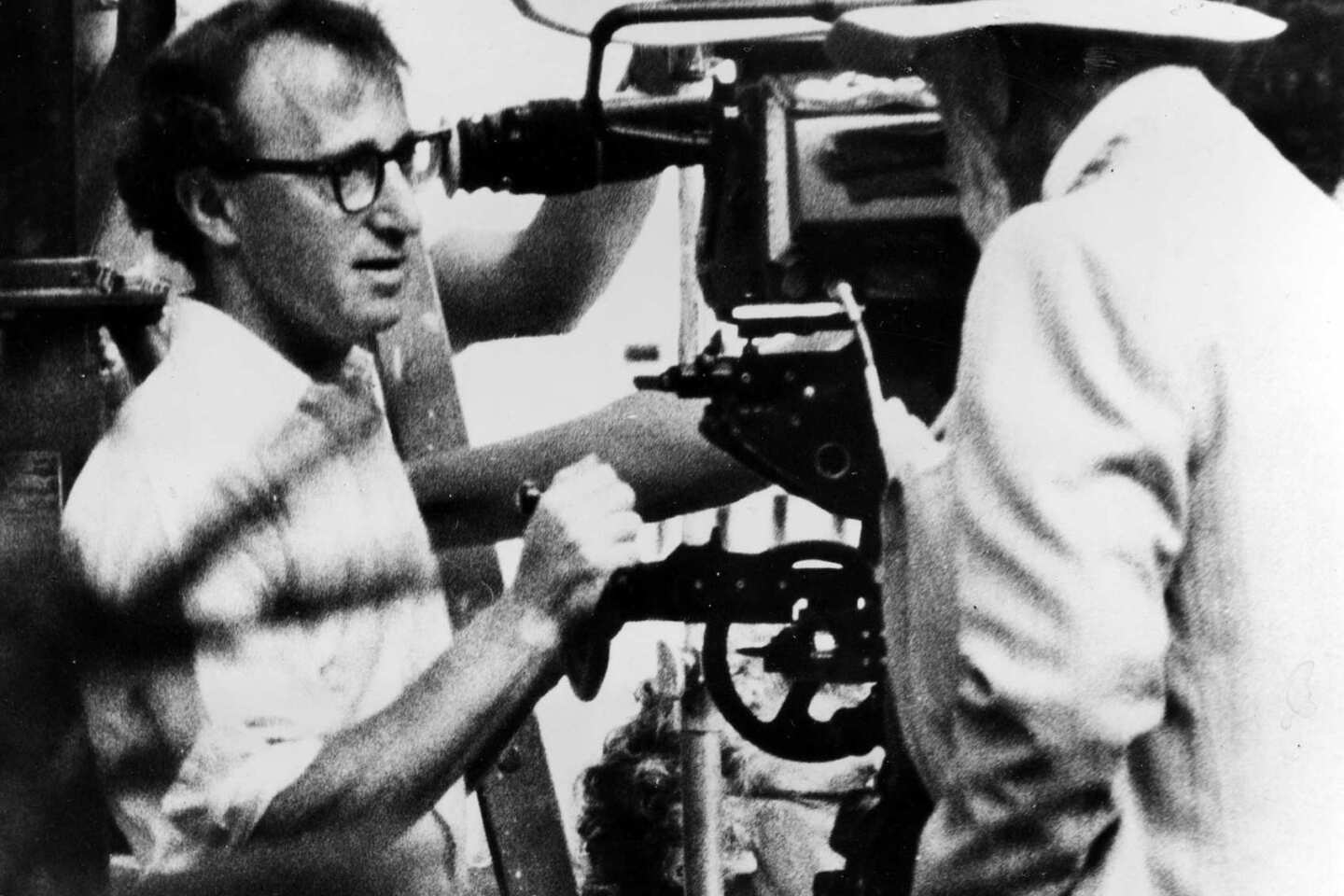

Working from screenwriter Lewis John Carlino’s adaptation of David Ely’s novel, Frankenheimer establishes not just unease but a soul-sick desperation from the opening moments, abetted by cinematographer James Wong Howe.

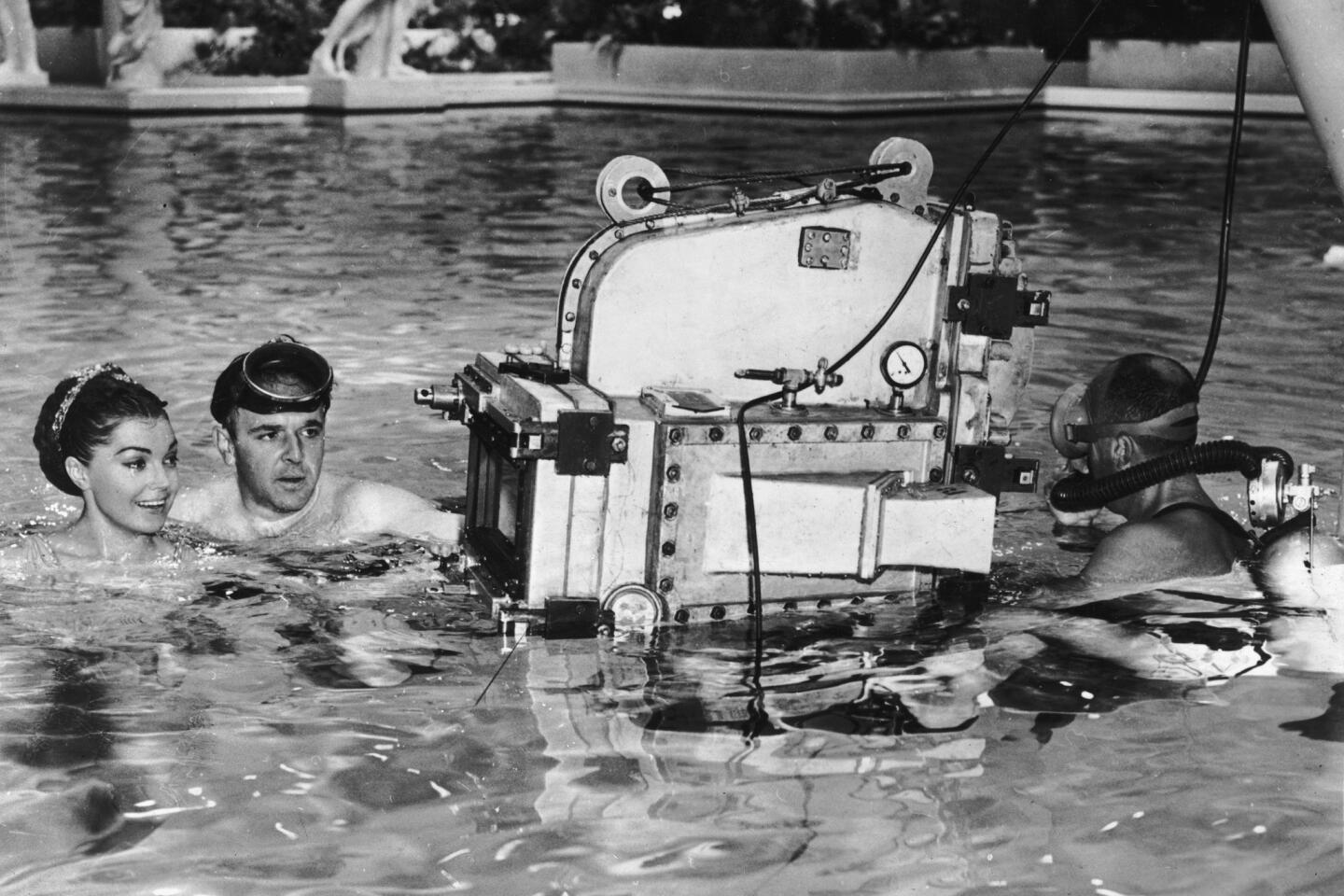

A photographer-turned-filmmaker, Frankenheimer was a visual stylist who embraced documentary-style shooting — eschewing process shots and using footage of an actual rhinoplasty in the Arthur-to-Tony transformation (the essence of restraint compared to the graphic images that have become standard TV fare). The mixture of a vérité approach and highly stylized noir lighting is essential to the movie’s surreal and sinister mood. Howe’s pre-Steadicam innovations and his use of wide-angle and fisheye lenses are often jarring, but their aptness deepens on repeated viewings.

Summoned to an outfit known only as the Company, which promises a miraculous new lease on life for burnt-out middle-aged men, the main character begins a descent into Hades: first amid the hissing steam of a tailor shop, and then among the refrigerated cow carcasses at a meatpacking plant. — two of the most evocative locations in the film.

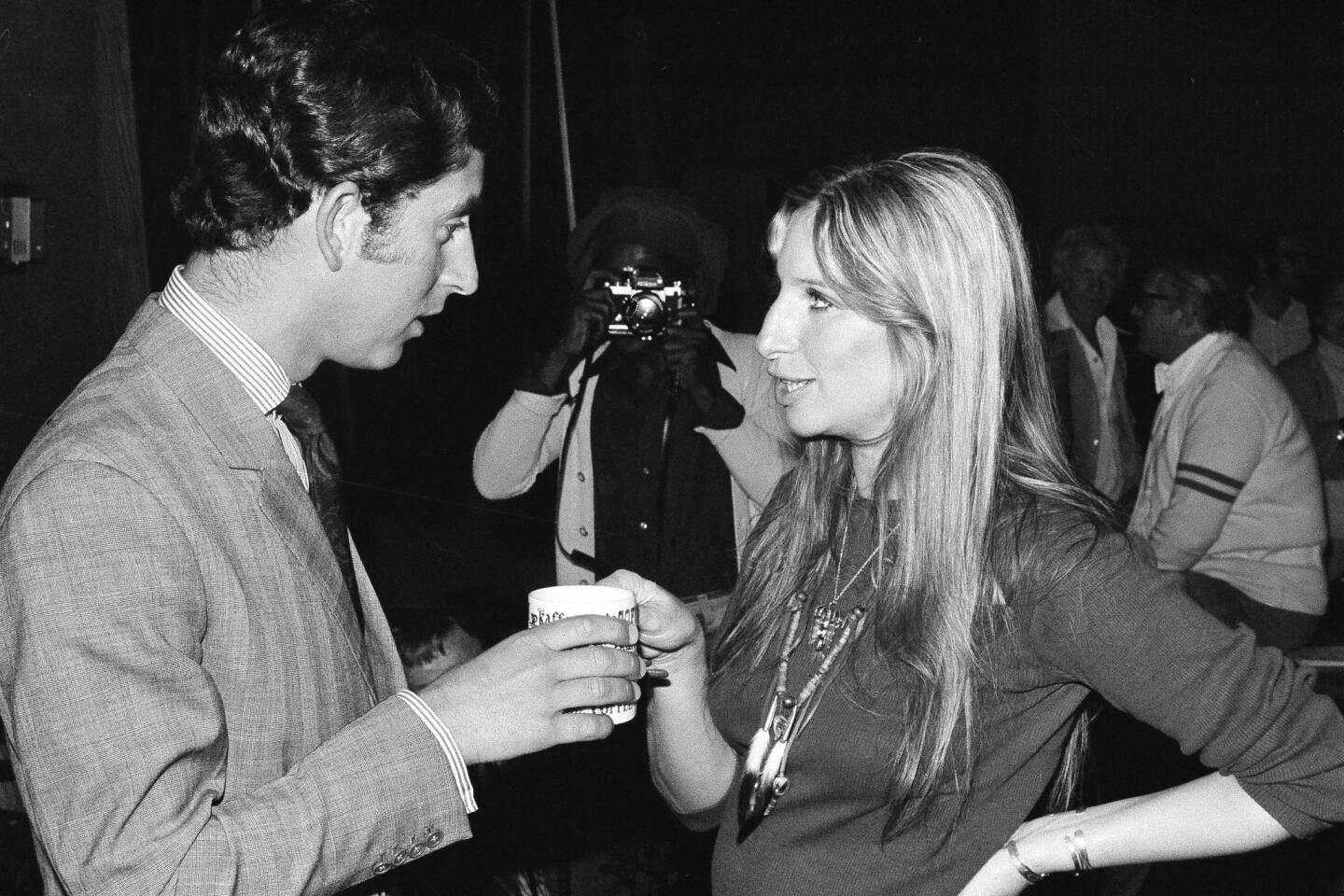

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

The sets for the offices of the Company occupy the other end of the visual spectrum, some of them built on a distorted, expressionistic scale that wouldn’t be out of place in “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.” In those offices, Randolph’s character is confronted by two key figures in the mysterious business, brilliantly played: Jeff Corey’s executive gives Arthur a peculiarly cheery hard sell, and Will Geer exudes an off-kilter, folksy sympathy. On the surface, they’re the flip side of the era’s Mad Men, questioning the status quo with their “expressional infrastructure.” But really they’re just selling the same old American dream, using a tried-and-true method: reinforcing doubt and dissatisfaction. Is that all there is?

It’s a question that doesn’t go away, even when Hudson’s “second,” or “reborn,” is set up in a Malibu beach house with a career as an artist. The California section of the film could have been better developed dramatically, but Hudson delivers some of his most powerful work. His wordless responses when, on separate occasions, two women describe him to himself resonate within the film and within the story of Hudson’s career, as one of the last studio-manufactured movie stars and as a man with a now famously secret life.

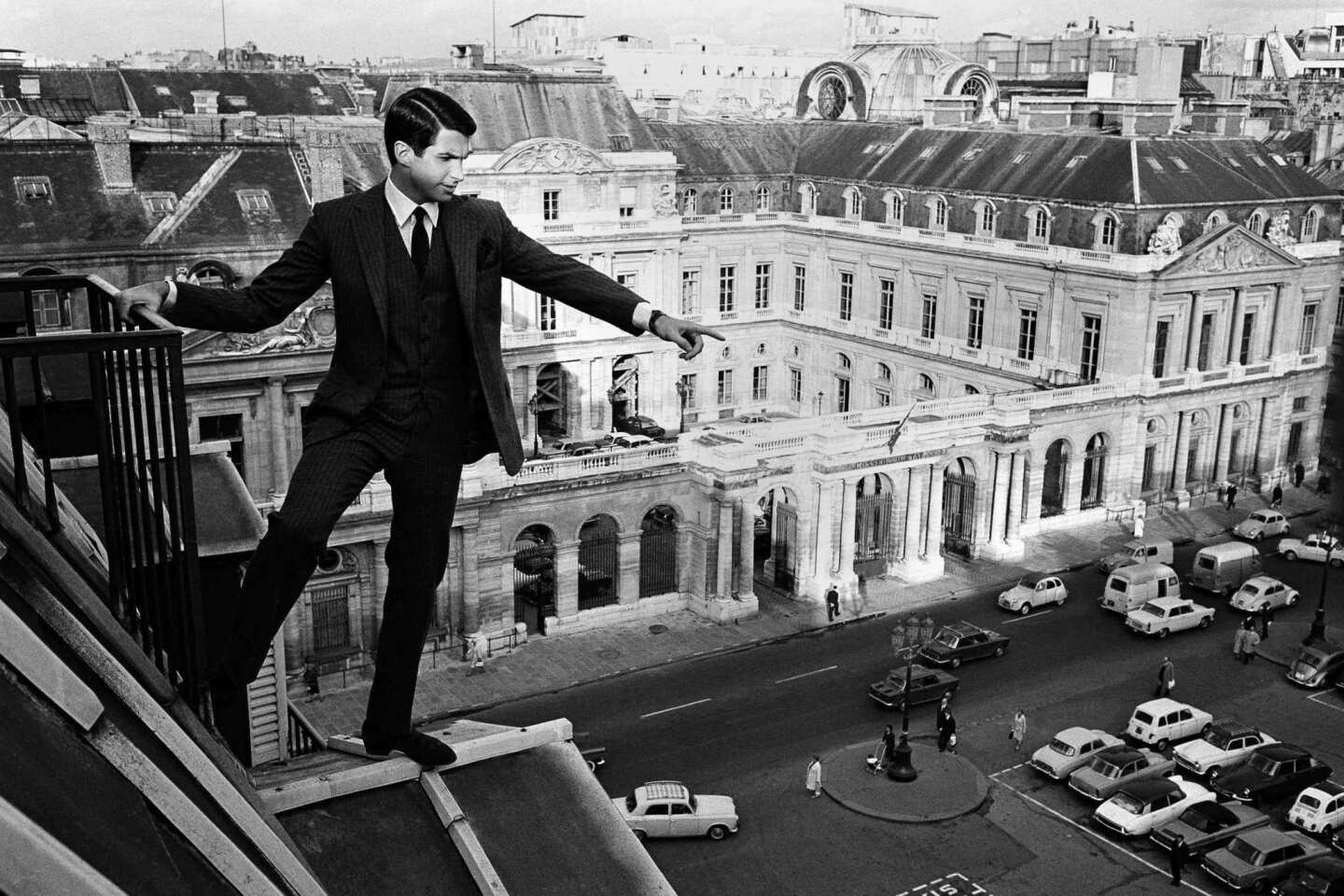

Speaking about “Seconds” a few years after its 1966 release, Frankenheimer characterized it as a movie that “went from failure to classic without ever being a success.” For the director, it was in some ways a turning point. It was his last black-and-white film (Howe’s too). His speed-and-glitz “Grand Prix” would soon follow, and after a period of erratic work he’d reconnect with audiences with “French Connection II” and “Black Sunday.”

But never again would he deliver such an uncompromising critique of modern life. Twenty-first-century technology and testosterone replacement therapy might make the premise of “Seconds” look reasonable rather than speculative. But though its suburban anomie is the stuff of midcentury culture, it remains a relevant dissection of consumerism and conformity, and a blistering portrayal of freedom: just another word for “sign on the dotted line.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.