Andrew Bird’s ‘My Finest Work Yet’ isn’t afraid to celebrate discomfort

- Share via

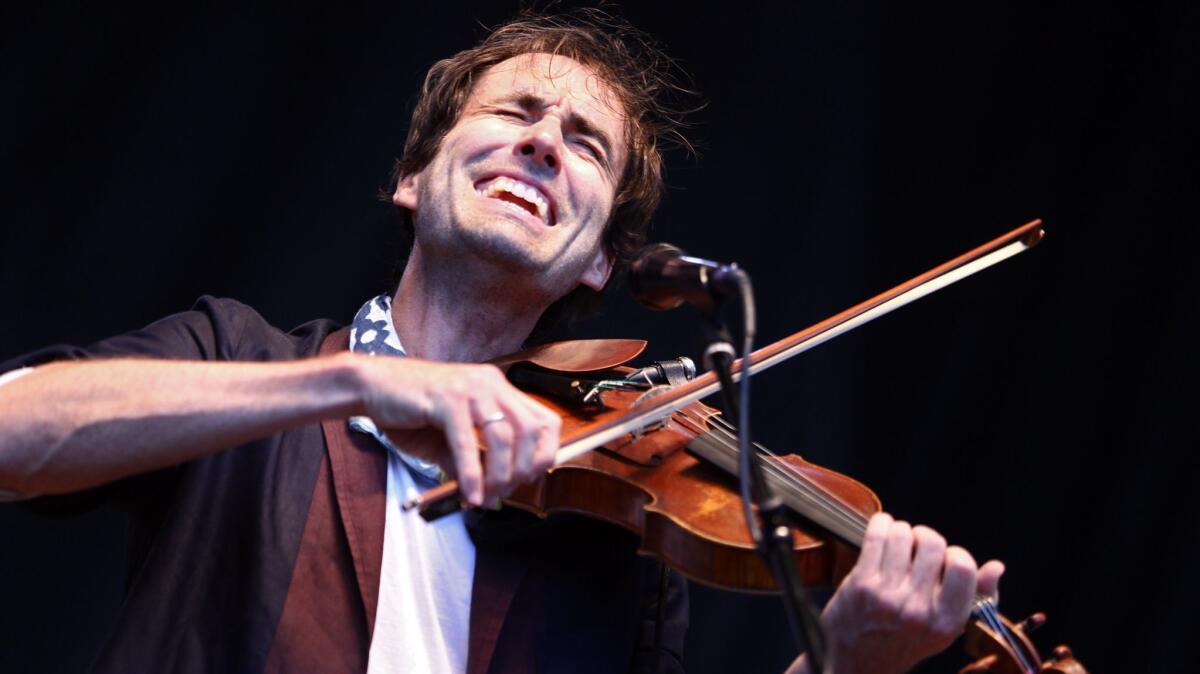

All kinds of ingredients go into the stone soup that makes up Andrew Bird. There’s acoustic old-time of a vaguely Appalachian bent, classical violin that comes out of Bird’s conservatory years, swing-era jazz, folk music somewhere between British and Baltic, uncanny whistling and a general guitar-based indie-rock sensibility.

And the music of the Chicago-reared, Los Angeles-based Bird is still more eclectic than that descriptor.

But there’s an extra additive that even most musicians who bend genres don’t typically include: discomfort. Bird’s new album, “My Finest Work Yet,” is out March 22.

“Total confidence is overrated,” Bird says a few days after a recent show at Largo at the Coronet in a Los Feliz coffee shop not far from his home. Bird often plays songs before they are finished, not just for what he can learn from the experience, but for the way it makes him feel. “I like it when the songs are in that disloyal, malleable state. I get a kick out of the embarrassment.”

The new album’s inspiration is politics, especially issues around gun safety and climate change, which have been in Bird’s mind since the arrival of his young son. But here, too, he doesn’t want to do things the obvious way. “I want to talk about things we’re not talking about as a people,” he says. “What can I say that’s gonna be on a different frequency than everything else?”

Though Bird is not yet 50, his emergence as someone with co-conspirators like Fiona Apple, KCRW’s Anne Litt, Dave Eggers and John C. Reilly has been a long time coming — at the Largo show, he spoke with artist Shepard Fairey about his process. Bird’s first serious musical investment came at the age of 4, when his parents signed him up to study the violin.

It’s easy to see how the young Bird, who retains the intensity and introversion of a child prodigy, would respond to the focused dedication required to master a classical instrument. Eggers, who shows up in the liner notes to Bird’s new LP, overlapped with him at the same suburban Chicago high school, where they worked on a literary magazine but didn’t know each other.

Bird’s first real bands formed while he attended conservatory at Northwestern. By day he’d study violin and music theory, by night he’d play in Irish groups or punk and ska bands around Chicago. These early club experiences made a strong impression on him. “I was underage, girls were dancing…” he recalls, voice trailing off.

Early on, Bird responded to rustic songwriters with a gift for distillation – Townes Van Zandt, John Prine, and a bit later, Southern Gothic singer Bobbie Gentry.

Along the way he also developed a serious love for pre-modern jazz, especially the tenor saxophonist Lester Young, perhaps best known for his duets with Billie Holiday. Bird says he plays violin like a tenor, but that his connection to “Prez” goes beyond mere influence. “I used to listen to records as textbooks – I’m gonna do this. But when I heard Lester Young, I just listened.”

After a brief stint with swing revivalists Squirrel Nut Zippers, Bird began releasing records under his own name (originally with a group called Bowl of Fire) that found the common ground between gypsy jazz and Weimar despair.

He’s demonstrated a commitment to quixotic projects -- an entire album of Handsome Family covers and another inspired by the Los Angeles River. With “My Finest Work Yet,” he’s made an album influenced by jazz of the post-Sputnik era, that sounds entirely like something else.

When Bird talks about “My Finest Work Yet,” whose title seems half-ironic, he talks mostly about record production. He’s especially taken by the style pioneered by producer Rudy Van Gelder, whose New Jersey studios served as legendary incubators for artists like Miles Davis, Grant Green and Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

But Bird’s album does not sound like a jazz record; rather, its recalls the sound Largo’s Jon Brion brought out in Aimee Mann, Brad Mehldau and Robyn Hitchcock.

But Bird has spent years thinking about what the room an album is recorded in does to the music. “I’m obsessed with space, and how your sound waves are bouncing off that space,” he says. “Van Gelder’s real magic was creating a room sound that you would re-create in your own room.”

The producer used what’s called “bleed,” meaning numerous instruments or voices show up on every channel. “It goes against the trend of the last 30 to 40 years, which is to isolate every sound and manipulate it [later] in the mix.”

The composer Gabriel Kahane thinks Bird has “crafted a sound world that’s completely his own. The way he treats his violin sonically, the kinds of textures that he draws out of his looping pedals, it feels to me very much akin to a composer whose primary interest is in color and timbre rather than harmony.”

This all sounds pretty technical, but these techniques allowed Bird to create a deeply resonant and fresh-sounding recording.

Bird seems like a man split in two pieces, maybe more. Besides the numerous genres he’s inhaled, which make him sort of indescribable, he’s motivated by both strong convictions and an inner need to be poetic and indirect. It all gives his work a complexity and range that’s not easy to attain.

When he plays, though, sometimes it’s pretty simple: “I want to write songs that make it easier to get to that place where you feel possessed,” he says.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.