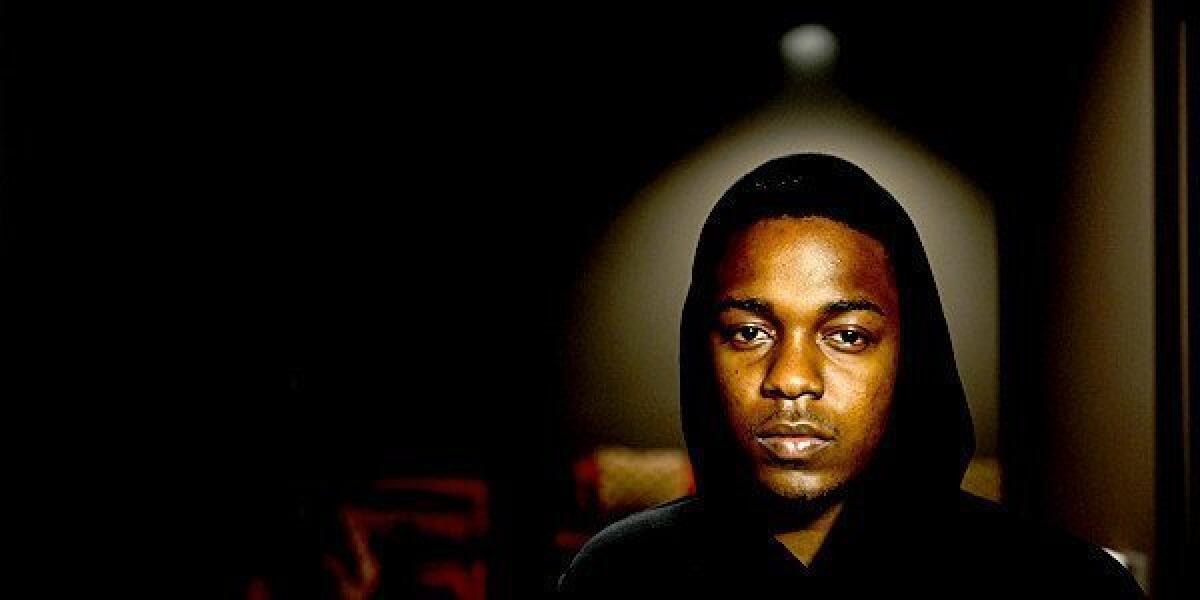

Kendrick Lamar, from one ‘good kid’ to another

- Share via

Backstage at Club Nokia last week, Compton rapper Kendrick Lamar prepared to play the first of two homecoming shows. It was around noon in the artist lounge, and save for the footsteps of a couple of crew members, the freezing room was silent. Lamar crouched in a corner, texting, his slight frame swallowed up by an oversized black hoodie. And when the 25-year-old did finally speak, it was to politely greet a guest in a whispery voice more fit for library study than freestyling.

Yet the unassuming Lamar — all 5 feet, 6 inches of him, stands a better shot of long-term stardom than any rapper to emerge from L.A. in a decade.

Widely considered the most promising figure to come out of West Coast hip-hop since the Death Row Records dominance in the 1990s, Lamar has been championed by Dr. Dre, who brought Lamar (and his L.A. label Top Dawg Entertainment) to Dre’s Interscope imprint, Aftermath.

PHOTOS: Celebrities by the Times

Now Lamar is in the elite company of label mates such as Eminem and 50 Cent and has a critically acclaimed, major-label debut to his name in “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” released Monday.

“I wanted to construct an actual album that makes sense, with a full story and a dialogue about what kids are going through and what my generation is reacting to,” Lamar said. “What I want is for someone, when they think about this album, is to say, ‘I know who that person is,’ not ‘That song went to the Top 40.”

Though an heir to a label that made its reputation with hyper-violent nihilism, Lamar is more introspective and self-interrogating than his predecessors. His records reflect the perspective of a watchful outsider detailing the dark allure of life in south L.A. County. But rather than succumb or revel in that culture, he unpacks the reasons why he wants in, and then looks for ways out.

PHOTOS: Hollywood backlot moments

“I turned 20 and realized that life wasn’t getting anyone anywhere,” he said. “You hear stories from the ‘80s about people selling dope and becoming millionaires, but in reality it’d just be guys walking around with $70 in their pockets. I knew I wanted something else.”

Lamar and his album defy easy stereotypes of what “Compton rapper” means in the pop culture imagination. Both his mother and father were present and strong figures in his childhood, and they make character cameos in the spoken-word interludes that feel like a Greek chorus of conscience, especially on the album’s emotional centerpiece, “Real.” “Any … can kill a man,” his father warns. “Real is responsibility. Real is taking care of your ... family.”

Although Lamar’s ‘90s L.A. rap ancestors could be painfully misogynistic, he has written women as complex characters and fellow travelers. “Keisha’s Song (Her Pain)” from 2011’s breakthrough digital album “Section.80” showed how his city posed its own particular perils for young women. On “good kid’s” poison-pillow-talk track “Poetic Justice,” he one-ups his guest Drake in detailing what a wounded lover’s heart wants — “If I told you that a flower bloomed in a dark room, would you trust it? … You’re in the mood for empathy, there’s blood in my pen.”

The album’s story is how that good kid navigates the Compton of his adolescence — a time well after crack cocaine had ravaged South L.A. and the L.A. riots exposed the city’s racial and economic wounds to the world. The album isn’t explicitly about those things, but their social consequences seep into the experience of the young Lamar narrating the album — along with the universal travails of bad love, manipulative friends and the pull of vices on tracks like the drug dream “m.A.A.d City” and “Swimming Pools (Drank)” that bravely tackles his binge drinking.

“I’ve got a good grip on it now, I don’t need to be dependent on liquor to feel good,” Lamar said. “At this point, you’re exposed to everything 10 times over, whatever your vice is, you have to show restraint every day towards it. You can get caught in situations you can’t get back, so I wanted to shine a light on it and not get caught in that B.S.”

Lamar calls the album “a short film” and when it’s over one does get a dazed feeling, like walking out of a movie theater. That storytelling craft earned him one of L.A.’s most devoted audiences and the ear of collaborators such as Lil Wayne and Lady Gaga.

But is that what a pop audience wants?

“Good kid” is singles-savvy (the technically astounding, ironically cocky “Backseat Freestyle” is already an Internet hit) and sonically enticing, with production work by known hit-makers like Pharrell Williams, Just Blaze, Hit-Boy and of course, Dr. Dre (though it’s telling that the album’s most obvious radio-baiter, the Dre-featuring “The Recipe,” with its paean to L.A.’s “women, weed and weather,” is consigned to a bonus disc). Even a decade ago, such a smart and snappy rap album championed by Dr. Dre on Aftermath would be guaranteed multi-platinum sales.

Lamar and his team have more complicated expectations for what a hit rap career looks like today. “Good kid” is a landmark record in L.A. hip-hop and one of 2012’s defining releases. But Dr. Dre and Interscope are in the business of making canonical, top-selling MCs, not well-regarded cult artists.

“There will never be another Jay-Z or Nas or Tupac,” Lamar said. “What I can do is continue their passion and work ethic while being true to myself.”

His team at Top Dawg Entertainment, the local label that Interscope bought out as part of its interest in signing Lamar, sees Lamar’s career as playing the long game. It is establishing a platform for his extended crew Black Hippy (with friends Ab-Soul, ScHoolboy Q and Jay Rock) to keep growing their own reputations and return L.A. to the center of the national hip-hop conversation. After that, no one can control what the market will do.

“The game has changed so much. But he is a special artist, he can do what Jay-Z did,” said Anthony Tiffith, the imprint’s founder. “At the end of his career, he will be seen as one of the greatest.”

Lamar seems at peace with the expectations and confident that as an album, “Good kid” might eventually have a shot at joining “The Blueprint” and “Illmatic” as a genre-remaking, legacy-sealing release — regardless of what the sales figures eventually yield.

If he needed proof, he got it when he saw the adoring crowds at Club Nokia at his two homecoming shows later that night. Judging by their ardor, they were waiting for this day right along with him.

“My family still has a place in Compton. I don’t live anywhere now, I’m a rolling stone,” Lamar laughed. “ But whenever I come back, I want to walk around the streets in Compton, to let some small boy see me know that ‘Hey, you can get to a better place.’”

PHOTOS AND MORE:

PHOTOS: Iconic rock guitars and their owners

The Envelope: Awards Insider

PHOTOS: Unfortunately timed pop meltdowns

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.