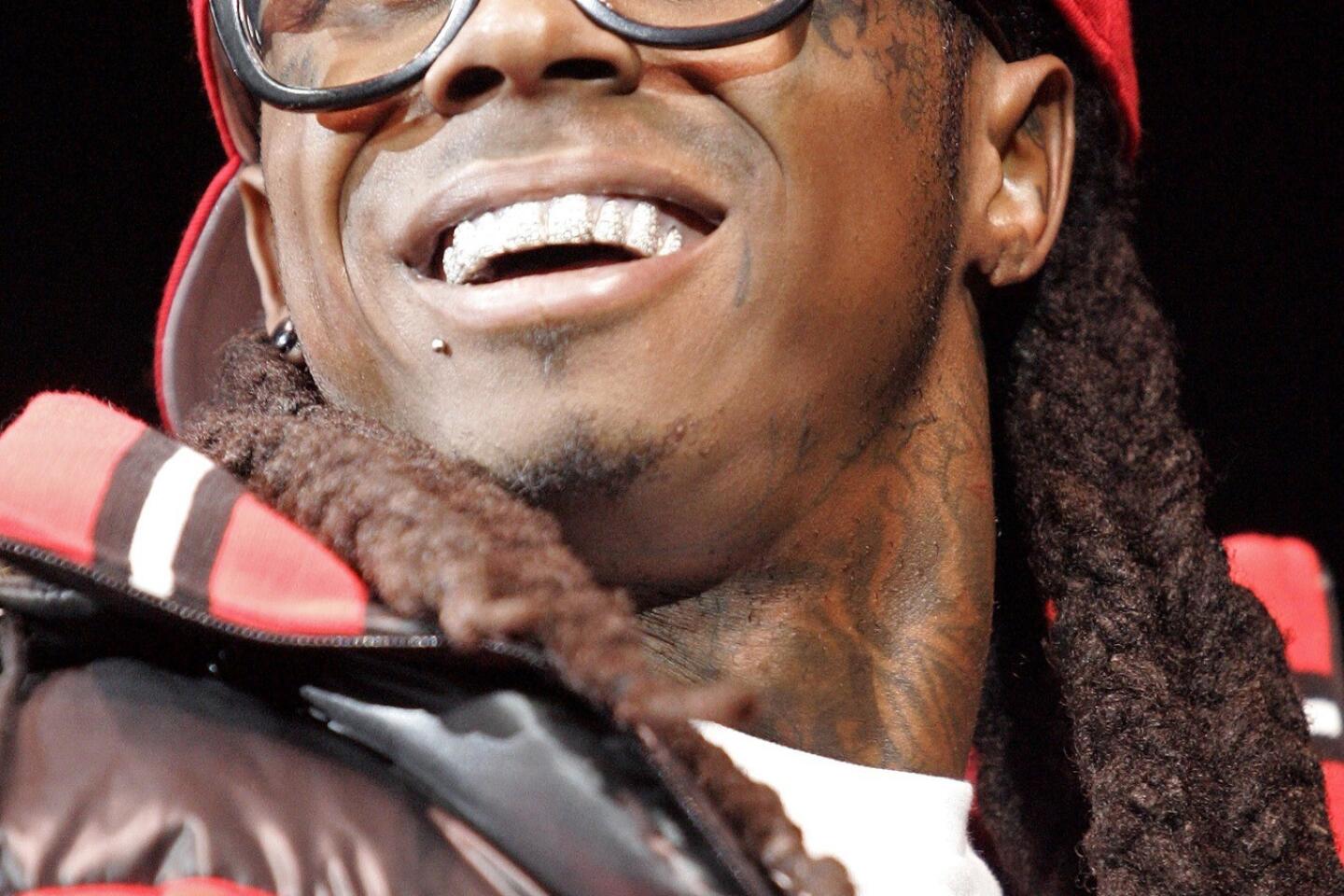

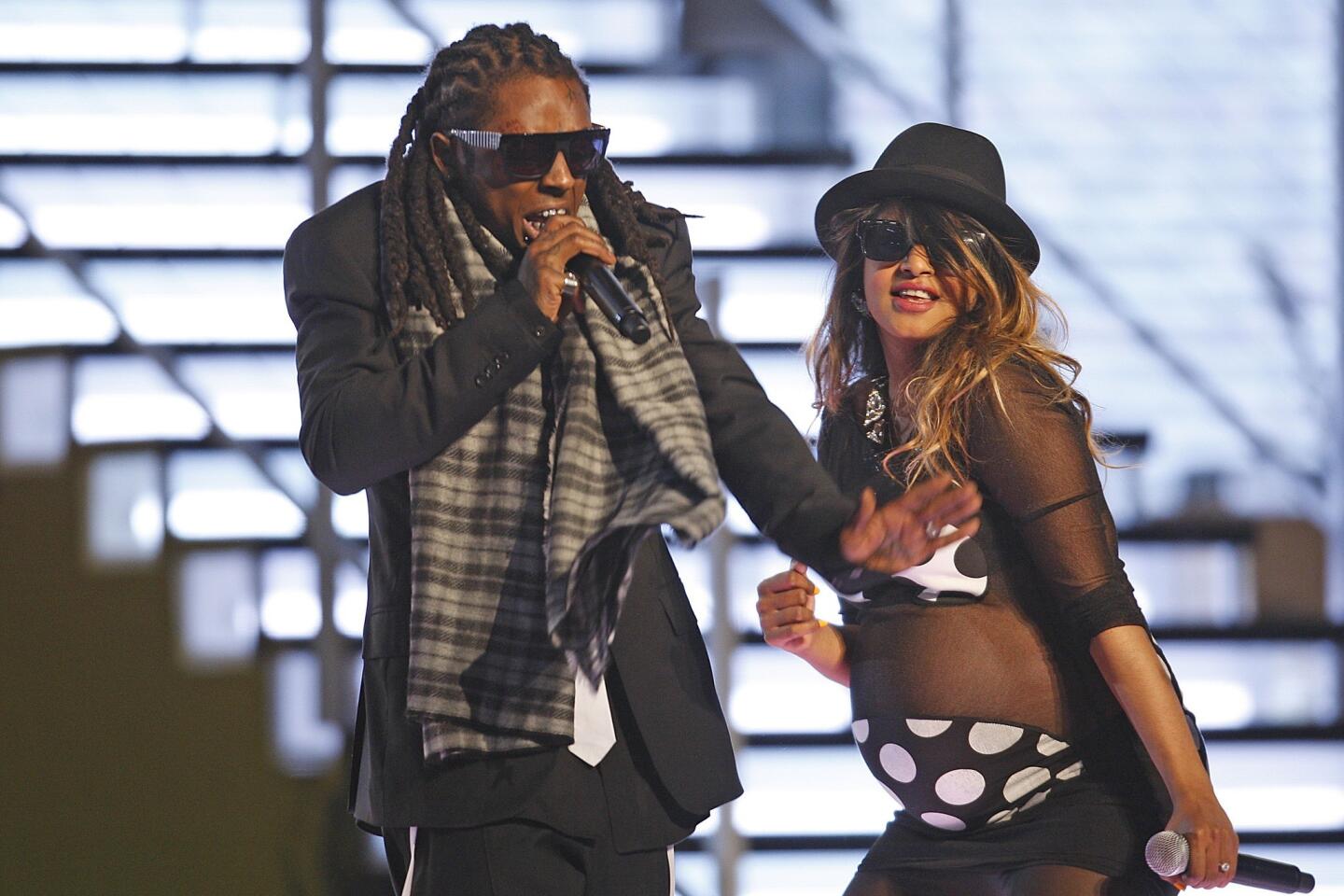

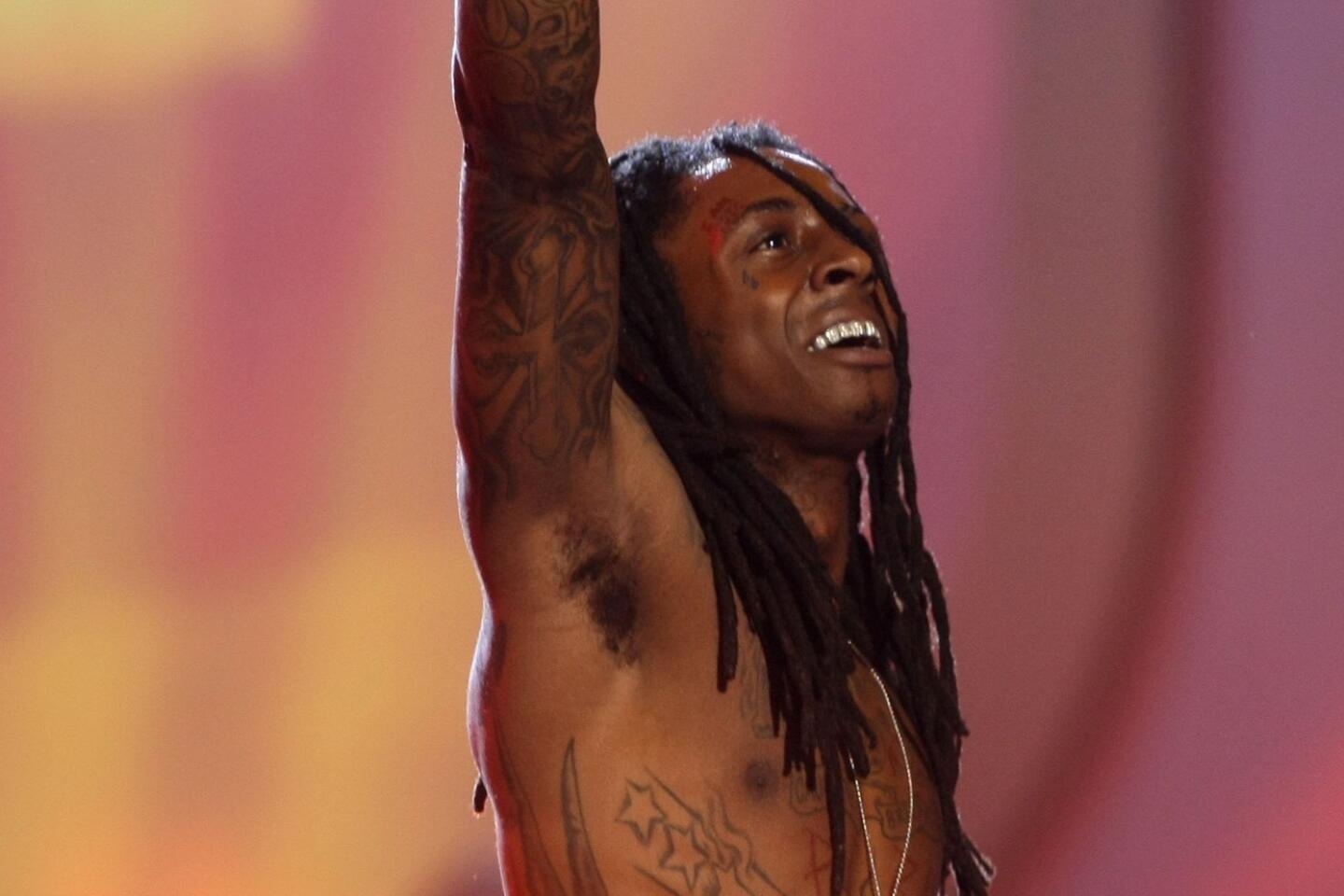

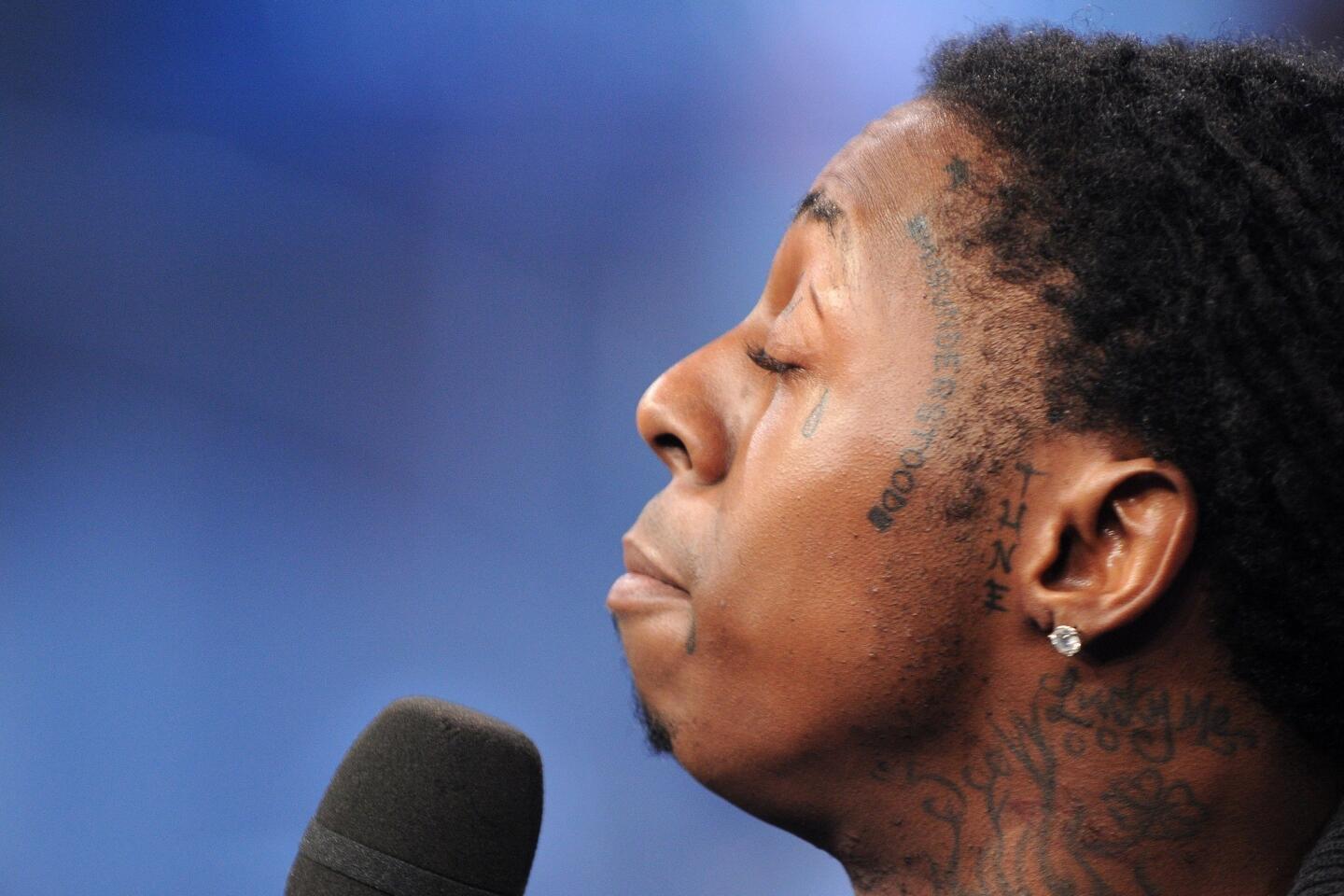

PepsiCo-Lil Wayne split marks shaky alliance of rappers, business

- Share via

Corporations are quick to recruit rappers to sell their soft drinks, shoes and smartphones — but the moment there’s a whiff of controversy, they are just as quick to cut them loose.

The latest example is PepsiCo and Lil Wayne. Last week, the soft drink company announced it had ended its relationship with Wayne, one of the biggest selling rappers in music, over a vulgar sexual reference to slain civil rights figure Emmett Till in a remix of Future’s hit, “Karate Chop.”

Wayne’s controversy followed similar flaps between PepsiCo and Tyler, the Creator over a video ad the rapper created that some deemed racist and sexist, and Reebok and Rick Ross after he rapped about slipping a party drug in a woman’s drink and taking her home.

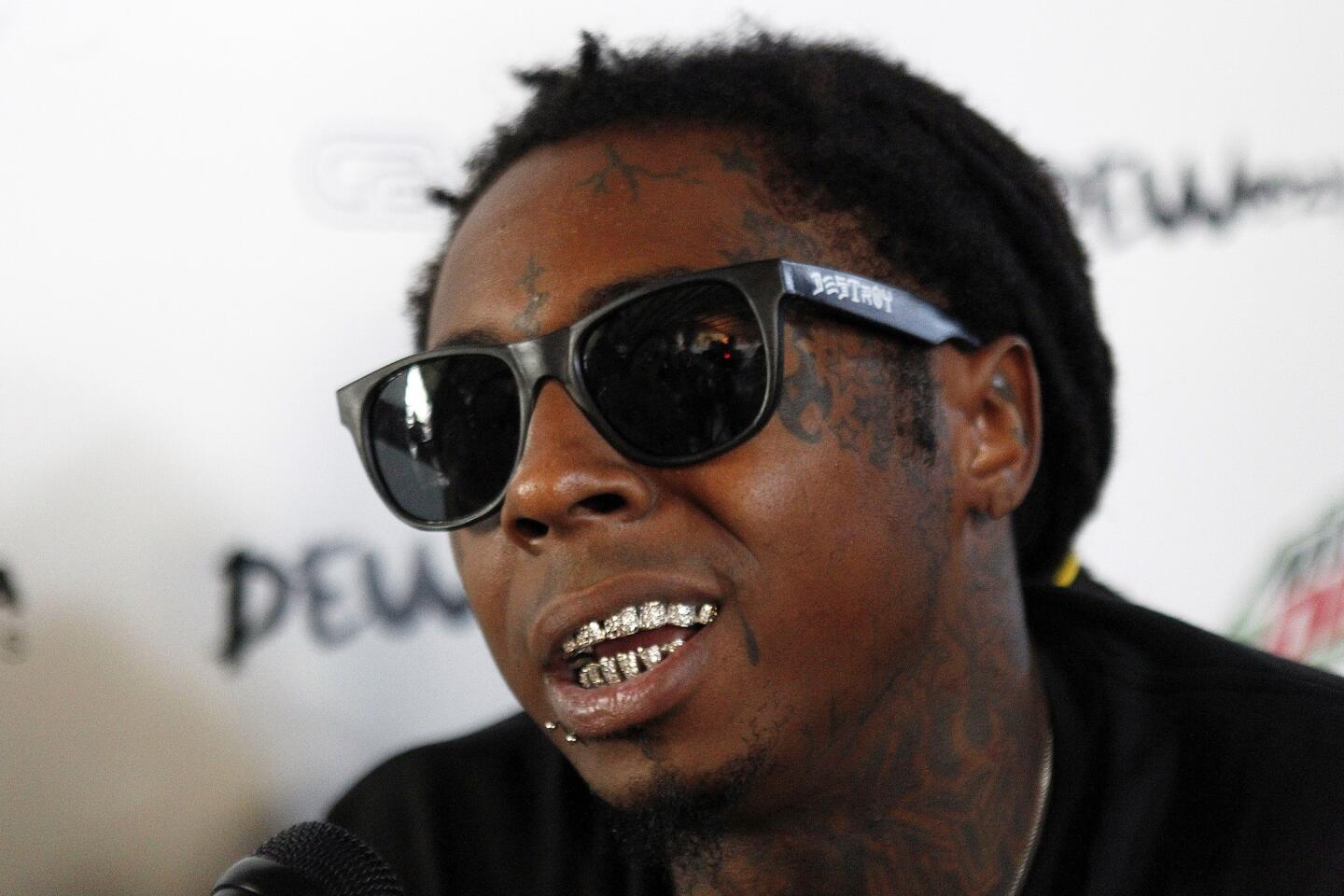

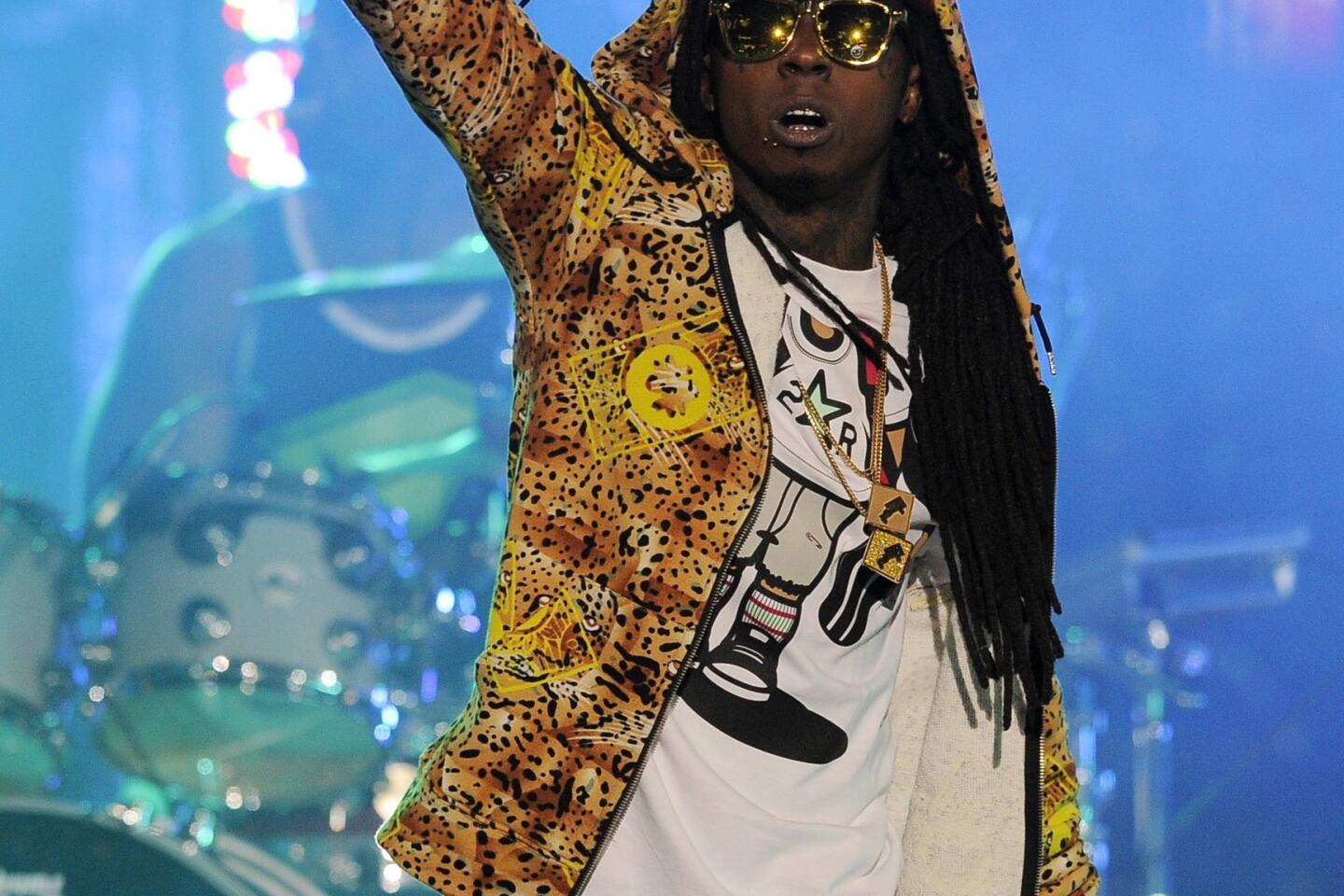

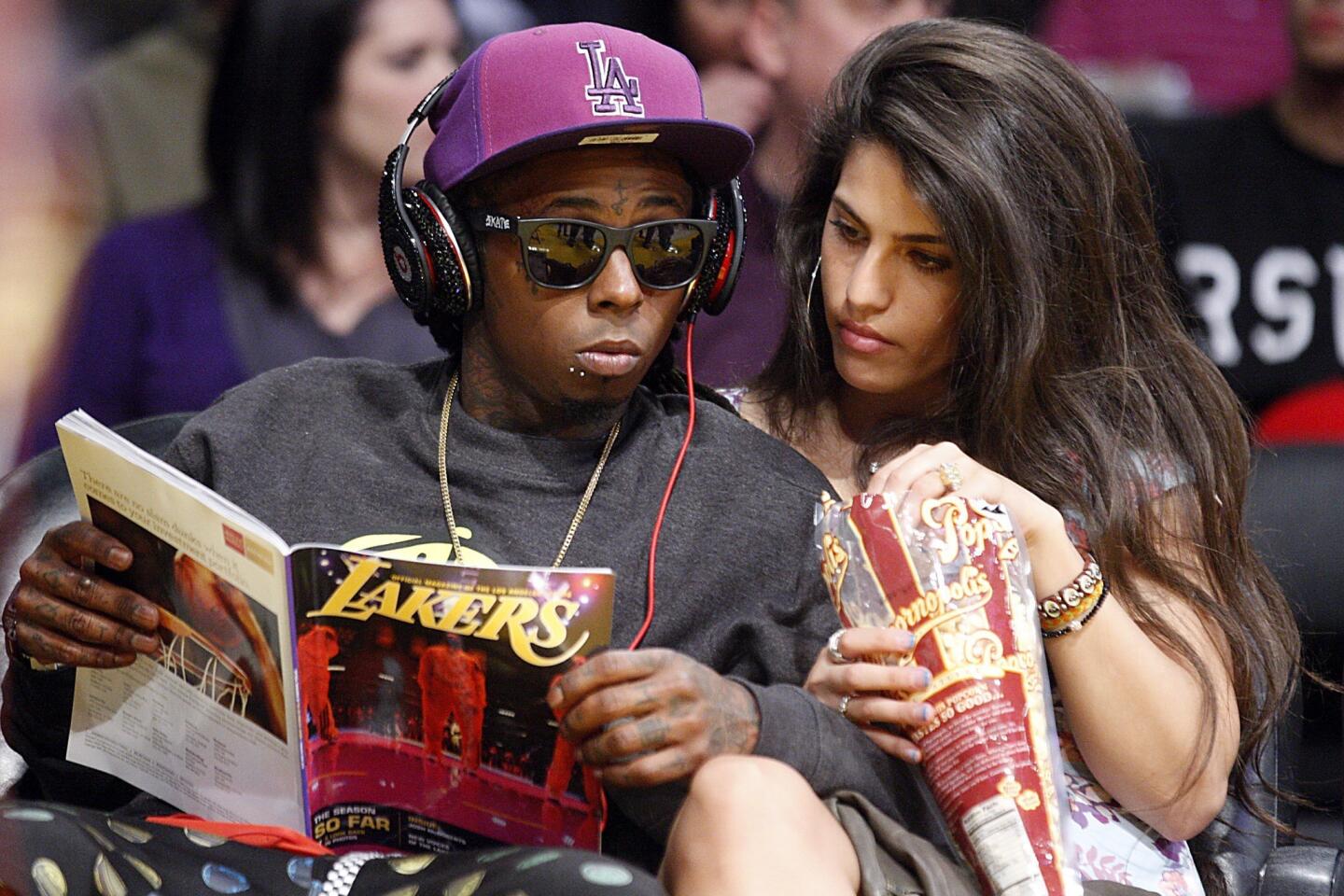

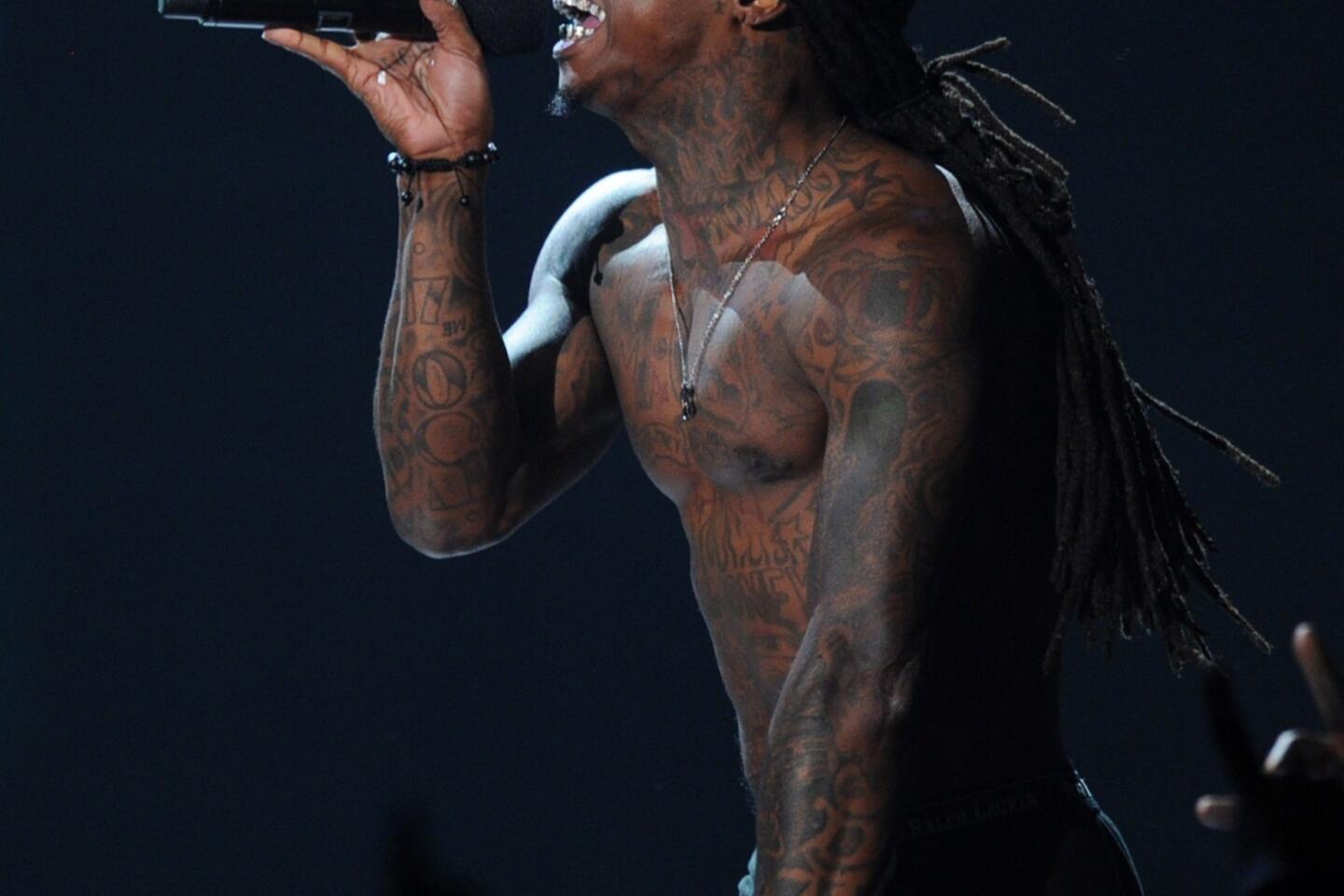

PHOTOS: Rapper Lil Wayne a.k.a. Dwayne Carter

Peter Sealey, a professor at Claremont Graduate University and a former head of marketing at Coca-Cola, said events like these prove how out of touch corporations can be when trying to appeal to younger demographics.

“When you market to youth there is a perennial battle in pushing the envelope without crossing boundaries,” Sealey said. “And when they do, they throw them under the bus. It’s hypocritical … but these guys in their late 40s don’t know who the hell these people are.”

Sealey says the hiring of potentially controversial rap artists also represents a generation gap within the corporations. “If [Tyler’s ad] had been seen by senior management, no way would that have gotten out.”

PepsiCo declined to comment for this article and requests for comment from Reebok went unanswered, but a person with knowledge of the deal who isn’t authorized to speak publicly said Wayne’s partnership with the soda company was worth more than $7 million, and Ross stood to make between $3 million to $5 million with the athletic company.

Ryan Ford, vice president of L.A.-based Cashmere Agency, has helped rappers like Snoop Dogg and Kendrick Lamar secure lucrative partnerships with brands such as Adidas, Samsung and Pepsi.

“Artists by their nature have a responsibility to be creative. Sometimes to achieve that, whether you’re a rapper or performer, you push boundaries,” he said. “When you take that unbridled creativity and attach it to a brand, the brand has very different motives.”

PHOTOS: The history of ‘sizzurp’ in song

Add to the mix social media, which is now playing a critical role in highlighting the more dysfunctional relationships that develop when art tangles with commerce, and these odd partnerships are being scrutinized much more frequently and in a bigger arena than in the past.

The feminist group Ultra Violet placed ads against Ross via Facebook and Twitter and garnered more than 100,000 signatures on a petition to have him dropped by Reebok. Till’s family took to YouTube to urge the public to boycott Mountain Dew, and both Tyler and Ross used Twitter to defend themselves during their controversies.

Following all the social media activity Pepsi severed ties with Wayne last Friday — just days after it had pulled the plug on a series of online Mountain Dew ads by Tyler. In April, Reebok split with Ross.

“People are tired of the music and the outcry is getting louder,” said Paul Porter, a music and media industry executive and founder of watchdog blog RapRehab.com. He was an integral force in the company nixing Tyler’s ads. “[Companies] are finally finding out that they can’t always connect their brands to artists that will give them positive results.”

Hip-hop fans and rappers like Snoop Dogg, Tyga and Meek Mill have been vocal in criticizing corporations dropping rappers over lyrics. It’s freedom of speech, they say. But more importantly they are questioning why brands are caving to public pressure against rappers they’ve signed, when they should have known their lyrical content was potentially offensive to wider audiences.

PHOTOS: Hip hop gone Hollywood?

Tyler was criticized for envelope-pushing lyrics seen as homophobic and misogynistic long before he linked with PepsiCo. And when Pepsi brashly said Wayne’s line about Till “does not reflect the values of our brand,” one could ask their stance on other lyrics, which are routinely peppered with references to “Molly,” the powder or crystal form of pure MDMA, and the addictive codeine and promethazine concoction “sizzurp.”

“It’s indicative of what brands have always done when they are involved with hip-hop culture,” said Latifah Muhammad, editor of Hip-Hop Wired. “They like to dip their toe, but not go all the way in. If they did, they would have known [Wayne or Ross] would rap about something that would get people mad.”

“It goes to show you how these corporations literally have no understanding of hip-hop and rap culture,” said Muhammad. “But they want to profit off of it.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.