Bison country is changing — and not for the better. But the future is unwritten

- Share via

This is the Sept. 29, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

For the second time in two years, I found myself staring down a herd of bison.

It was a gorgeous morning at Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota, home to vast grasslands pockmarked by prairie dog burrows and cavernous badlands carved by the Little Missouri River and its tributaries. I was joined by friends with whom I’d also hiked the Tetons last summer. Far from our homes in cities and suburbs, we were again confronted by the question of how to handle the massive horned beasts whose homeland we were passing through.

Were we really in danger? Probably not, as long as we didn’t get too close or antagonize the herd. But were we a tiny bit nervous as we scurried along the trail, peeking back over our shoulders to make sure the bison weren’t following us? Absolutely.

It was hard to imagine what the landscape must have been like two centuries ago, when as many as 60 million bison — also known as buffalo — roamed North America, before white colonizers nearly slaughtered them to extinction.

Today there are roughly half a million bison, up from fewer than 1,000 in 1900. It’s a conservation success story — and a reminder of the scars the United States continues to inflict on the natural world, and on the nation’s Indigenous inhabitants.

As my friends and I explored the Dakotas last week, hiking and camping and visiting historic sites, we were bombarded with reminders of those scars — and of the difficult-but-vital work of making amends and building a better future.

In the historic gold-mining town of Deadwood, S.D. — perhaps best known as the setting for the TV show “Deadwood” — we visited Tatanka: Story of the Bison. The museum illustrates the symbiotic relationship between bison and the Lakota people, who traditionally relied on the animal for food, clothing, shelter, religious ceremonies and more.

White settlers killed bison en masse as part of a strategy to wipe out Native American tribes by depriving them of sustenance.

In the neighboring city of Lead, we saw one of the biggest scars imaginable — a gigantic former gold-digging operation called the Homestake mine. It was developed in the 1870s by California business magnate George Hearst, who later served as a U.S. senator (and whose son, William Randolph, served as inspiration for “Citizen Kane”). We could only see the open-pit section of the mine, but some of the worst damage is underground, where tunnels stretch as far down as 8,000 feet.

Another deep scar: The U.S. government pledged all this land to the Lakota and other Indigenous peoples in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. When gold was found in the Black Hills soon after, colonists quickly violated the agreement.

Yes, the U.S. eventually protected some of its least-damaged lands, establishing national parks and monuments and wilderness areas. I love these places dearly. Watching the sun set along the Little Missouri River at our Teddy Roosevelt campsite last week took my breath away. Examining the honeycomb-like “boxwork” formations at Wind Cave National Park, by flashlight, was surreal — especially after learning that similar structures on Mars may be a sign of water.

But the “public lands” the U.S. has chosen to protect were stolen from Native Americans, just like the lands we’ve exploited for gold, timber and fossil fuels. Environmental historian Adam M. Sowards scrutinized that history in an L.A. Times opinion piece, comparing the designation of Yellowstone National Park with a law declaring much of the public domain open for mining.

“Both laws seized land from its original inhabitants and also revealed a fundamental idea that animates American culture and law: Land is meant to be owned or controlled,” Sowards wrote this week. “From that perspective, tonnage and tourism, price per ounce and entrance fees, show themselves as simply different forms of commodification.”

I realize I’m not saying anything especially new. It’s been three decades since Kevin Costner — who financed the Deadwood bison museum — won a bunch of Academy Awards for “Dances with Wolves,” which explored the Lakota’s plight as American “pioneers” marched west. And the destruction wrought by mining, logging and fossil fuel extraction is well known.

But now that climate change has entered the picture, everything old is new again.

Global warming is resulting in smaller bison. It’s adding to the urgency of preventing out-of-control wildfires by setting prescribed burns, like the one that shut down a trail my friends and I had hoped to hike in Teddy Roosevelt.

Heat-trapping fossil fuel pollution is also loading the dice for bigger and more destructive floods — floods like the one that killed 238 people in Rapid City, S.D., in 1972. It was hard to imagine that kind of devastation last week as we strolled through the city’s tranquil downtown, which features life-size statues of every U.S. president through Barack Obama.

And in another twist on past harms, energy projects are once again facing conflict and criticism.

Driving north toward Teddy Roosevelt, I saw wind turbines on the horizon — and soon learned that Stark County, N.D., temporarily banned wind-farm construction last year, an example of the tension between big cities that need renewable power to fight climate change and rural towns that sometimes don’t want wind farms in their backyards. I picked up a copy of the Billings County Pioneer and was greeted by a front-page story about the challenge of transitioning to clean energy while keeping the lights on.

If I were an activist, I might tell you solving climate change and confronting environmental injustice would be easy if only the U.S. could get its act together politically. If I were a cynic, I’d tell you we’re too late, the time for solutions is long past, and we’d better come to terms with an ever-more-apocalyptic future where only the rich and powerful prosper.

The reality is more nuanced, because of course it is.

Yes, the future looks bleak — even a weeklong vacation to some of the most beautiful country I’ve ever seen couldn’t provide a full escape. But history hasn’t come to an end. The arc of the moral universe is being bent forward and back all the time.

Those wind turbines on the horizon? Whatever the barriers to future clean energy growth, they got built. Nearly one-quarter of U.S. electricity came from renewable sources in the first half of 2022. The prospects for continued growth are strong.

The future of the American bison? We may never see the beasts return to historic levels. But Indigenous tribes are playing a lead role in restoration efforts, working to build healthy ecosystems that might stand a chance against the warming planet.

And all that stolen land? I won’t pretend there are easy answers. But renaming sites that once honored people who did violence to Native Americans — such as South Dakota’s Black Elk Peak, previously Harney Peak, the highest point in the U.S. east of the Rockies — feels like a reasonable start. I’d also recommend paying attention to the LandBack movement, which has a goal of returning sacred lands in the Black Hills to Indigenous peoples.

Those lands include Mt. Rushmore. I’d never seen the national memorial before, and I’m not going to lie, I was impressed. It’s big. The faces of Washington, Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt and Lincoln are elegantly carved. The history is fascinating.

But I was glad my friends and I also visited the nearby Crazy Horse Memorial. Under construction since 1948 and bigger than Rushmore, the mountain sculpture honors a Lakota warrior who helped lead his people to victory at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. An on-site museum tells Crazy Horse’s story and features amazing Indigenous artwork.

A scale model of the unfinished monument features an inscription from its sculptor, Korczak Ziolkowski.

“This land of refuge to the stranger was ours for countless eons before: Civilizations majestic and mighty,” he wrote.

Just like last year’s Tetons trip, I returned from the Dakotas just in time to attend services for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. And just like last year, the words of the Unetaneh Tokef prayer struck me with renewed meaning as I reflected on my trip:

“On Rosh Hashanah this is written; on the Fast of Yom Kippur this is sealed: How many will pass away from this world, how many will be born into it; who will live and who will die; who will reach the ripeness of age, who will be taken before their time; who by fire and who by water; who by war and who by beast; who by famine and who by drought...”

Whether or not you believe in a higher power, the reality is we’re making those kinds of life-and-death decisions all the time — as individuals, as communities, as a species. We hold our collective fate in our own hands.

Hopefully, the future includes more bison. And hiking trips.

On that note, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

There’s a climate crisis reckoning underway in Northern California, where wildfires are decimating rural towns — and residents insist on rebuilding, even when more destruction is likely. In an important and superbly written series of columns, Erika D. Smith and Anita Chabria of The Times make the case for no longer spending billions of dollars rebuilding towns that may just burn again. They also examine the pervasive climate skepticism in these rural communities, and the terrifying reality that global warming is fueling dangerous right-wing extremism. And lest anyone accuse Erika and Anita of lacking sympathy for some of the state’s most vulnerable residents, they do an amazing job of explaining what people love about these places, especially in their final piece. But the sad reality, they write, is that “we can no longer afford to remake the past, even if we loved it.”

A bill from U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin III that would have sped up the permitting process for all kinds of energy projects — dirty and clean alike — is dead, at least for now. Democratic leaders in Congress agreed to hold a vote on the bill in exchange for Manchin, a West Virginia Democrat, supporting President Biden’s sweeping climate legislation last month. But Manchin couldn’t drum up enough support among Republicans, who were mad at him for supporting the climate legislation, my colleagues Freddy Brewster and Nolan D. McCaskill report. Some climate advocates applauded the Manchin bill’s failure, saying it would have been a giveaway to fossil fuel companies. But others were frustrated, arguing the bill would have boosted the clean energy transition by making it easier to build long-distance electric power lines, as Jeff St. John writes for Canary Media.

The California Public Utilities Commission has detailed the actions that might make it possible to shut down the Aliso Canyon gas storage field outside Los Angeles, seven years after a record-breaking methane leak. The proposal involves reducing the need for natural gas in the L.A. Basin, in part by replacing gas appliances with electric alternatives, as the L.A. Daily News reports. Whether or not the Public Utilities Commission chooses to shut down Aliso, statewide efforts to move away from fossil gas are already underway. The California Air Resources Board voted this month to move toward banning the sale of new gas-fired space and water heaters by 2030. And the Public Utilities Commission voted to end the practice of subsidizing gas hookups in new homes and businesses, which cost the state $622 million over the last five years, Kavya Balaraman writes for Utility Dive.

AROUND THE WEST

The California desert city of La Quinta has rejected a controversial surf park. Yes, a surf park in the desert — and not the only one that’s been proposed in the Coachella Valley a few hours east of Los Angeles, one of the state’s hottest and driest regions. The Times’ Ian James wrote about the debate over surf resorts in the desert, and about La Quinta’s decision to reject this particular proposal. This is all playing out in a part of the state hugely dependent on the Colorado River — a waterway crucial to much of the American West, which is now grappling with the consequences of irresponsible decisions made a century ago, as The Times’ Michael Hiltzik notes in a damning column on the 100th anniversary of the Colorado River Compact. And of course, the Colorado isn’t the only key water source in trouble. Californians should expect a fourth year of drought, Hayley Smith writes.

Climate change has hit California hard this month. A worker at an Amazon air freight hub in San Bernardino recorded a 121-degree temperature on the facility’s tarmac — just one example of what employees say can be an unsafe workplace during heat waves, my colleague Suhauna Hussain reports. In the mountain community of Forest Falls, a woman was found dead after the town was inundated by a debris flow, caused by heavy rainfall in a wildfire burn scar. As Melissa Gomez writes, this kind of wildfire-rainfall-mudslide tragedy is increasingly common in the San Bernardino Mountains. Not good. On our daily podcast, The Times, I joined host Gustavo Arellano and several colleagues to discuss record-breaking heat, drought, floods and more.

“Migratory shorebirds are incredible creatures that connect us globally. On their long journeys, they rely on wetlands across the Great Basin.” So writes Daniel Rothberg, describing his fascinating new story for the Nevada Independent on efforts to restore habitat in the Nevada desert and support these birds. There are parallels across the West, from California’s Salton Sea to Utah’s Great Salt Lake.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

California officials could soon vote to ban the sale of new diesel big rigs by 2040. This would follow the state’s recent move to ban the sale of most new gasoline-fueled passenger cars by 2035, as my colleagues Rachel Uranga and Christian Martinez report. Still, electric vehicles won’t solve all our problems. As Paul Thornton, an editor on The Times’ Opinion desk, writes, “In the end, an electric car is still, well, a car — and mass car ownership has devastating environmental consequences beyond tailpipe emissions.” One possible solution: Gov. Gavin Newsom just signed a bill banning local governments from mandating parking spots in new housing near public transit, in part to reduce the need for cars. Details here from Andrew Khouri.

A bill that would make it easier for utility companies to bury power lines — and thus prevent wildfire ignitions — awaits Gov. Gavin Newsom’s signature. But a prominent consumer advocacy group is urging him to veto it, saying it would increase energy bills by allowing utility companies to charge ratepayers for expensive undergrounding projects, Rob Nikolewski writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune. In related news, the U.S. Forest Service launched a criminal investigation into Pacific Gas & Electric’s possible role in igniting California’s biggest blaze of 2022 thus far, the Mosquito fire, George Avalos reports for the Mercury News. And several families are suing Southern California Edison over the deadly Fairview fire, saying the utility should have de-energized its power lines beforehand, The Times’ Summer Lin reports. It’s not yet clear what caused either conflagration.

The California Supreme Court has ruled that bumblebees can be protected under the state Endangered Species Act, even though the law doesn’t explicitly mention insects. Here’s the story from my colleague Louis Sahagún, who notes that bees can now technically be classified as “fish” under the law. In other endangered species news, Louis wrote about scientists depositing 200 yellow-legged frogs in San Gabriel Mountains streams, in some of the wildest and most remote spots in Los Angeles County. Here’s hoping the frogs survive and thrive. Louis also wrote about the contentious debate over Southern California’s urban coyotes. Should we try to exterminate these creatures, which have been here for 47,000 years? Or can we learn to live with them?

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

America’s first large solar-plus-wind-plus-batteries project is now online in Oregon. The more we can bring renewable energy and storage together, the easier it will be to replace traditional fossil-fueled power plants, as the Associated Press’ Gillian Flaccus notes in her story. She also points out that at maximum output, the Oregon facility will produce more than half the power of the state’s last coal plant, which was demolished this month; Oregon Public Broadcasting has video of the smokestack explosion. Here in California, Sacramento’s municipal electric utility just signed the largest-ever U.S. contract for a flow battery, a long-duration energy storage alternative to lithium-ion batteries. Canary Media’s Julian Spector has more.

Installing more electric car chargers at workplaces would help reduce planet-warming pollution while keeping the lights on. That’s according to a new study, which found that more workplace charging stations would help people fuel up during the day, when solar power is abundant, rather than charge at home in the evening when the power grid is already strained, my colleague Grace Toohey writes. In other electric vehicle news, the federal government is ready to start distributing billions of dollars from last year’s infrastructure law to build the first nationwide network of charging stations, the Associated Press’ Hope Yen writes.

Energy-efficient LED lights are great for reducing electricity use, and thus fighting climate change. But they can create terrible light pollution, blotting out stars in the night sky and harming the health of humans and migratory birds. The Times’ Sumeet Kulkarni wrote about possible solutions, including turning off unnecessary lights and requiring shields on outdoor light fixtures. But a few days after Sumeet’s story published, Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill aimed at reducing light pollution, saying it “may cost millions of dollars not accounted for in the budget,” as Corinne Purtill reports.

ONE MORE THING

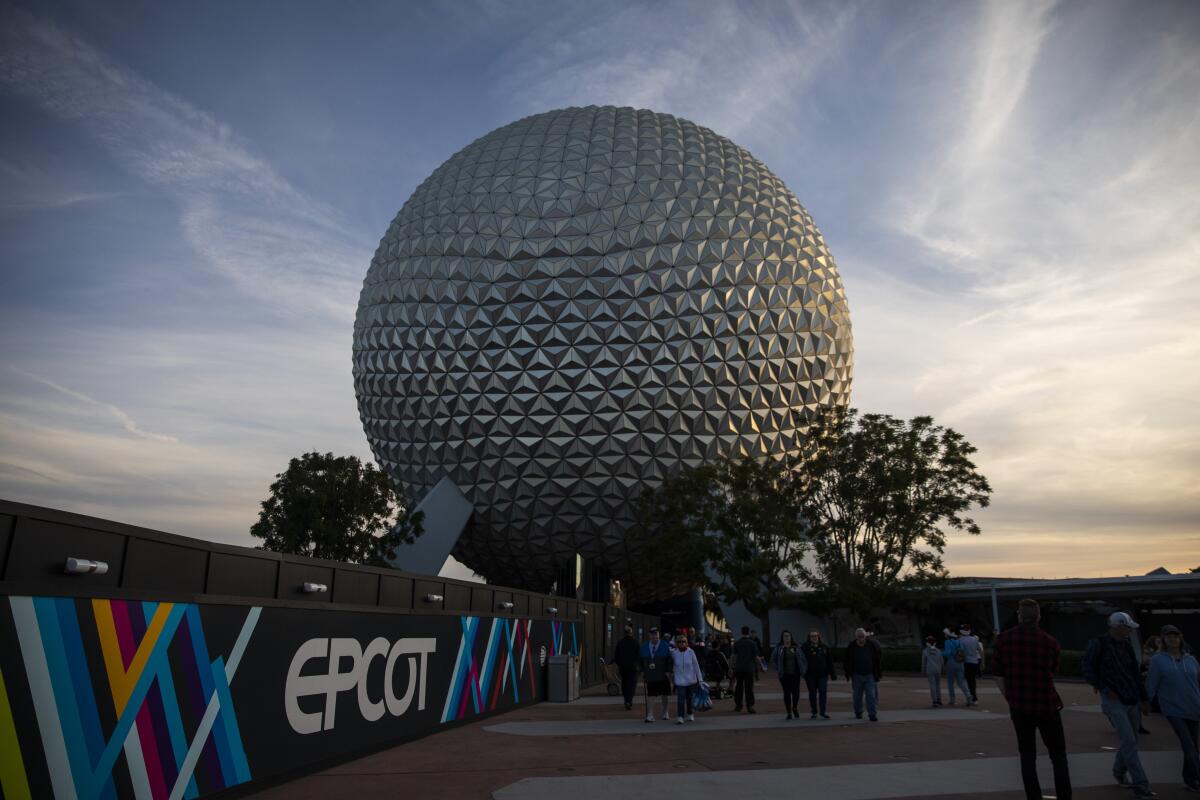

As Hurricane Ian barreled toward Florida this week, Walt Disney World announced it would shut down for at least two days.

I realize the temporary closure of a theme park is a tiny concern relative to the widespread death and destruction the storm could cause. But for me, a big Disney fan, it’s an important reality check. Even the places we go to escape — the hiking trails, the baseball stadiums, the theme parks — aren’t immune to the ravages of a changing climate.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, or previous ones, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues. For more climate and environment news, follow me on Twitter @Sammy_Roth.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.