US transit ridership is down: Can San Diego’s speedy commuter rail plan buck the trend?

San Diego is mulling a plan to create a high-speed commuter rail network. Some experts question if it will work, given the region’s sprawl.

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — Elected officials are preparing to ask San Diegans to approve not one but two tax increases to fund billions of dollars in bus and rail investments, including a San Diego Grand Central Station to connect riders to the airport.

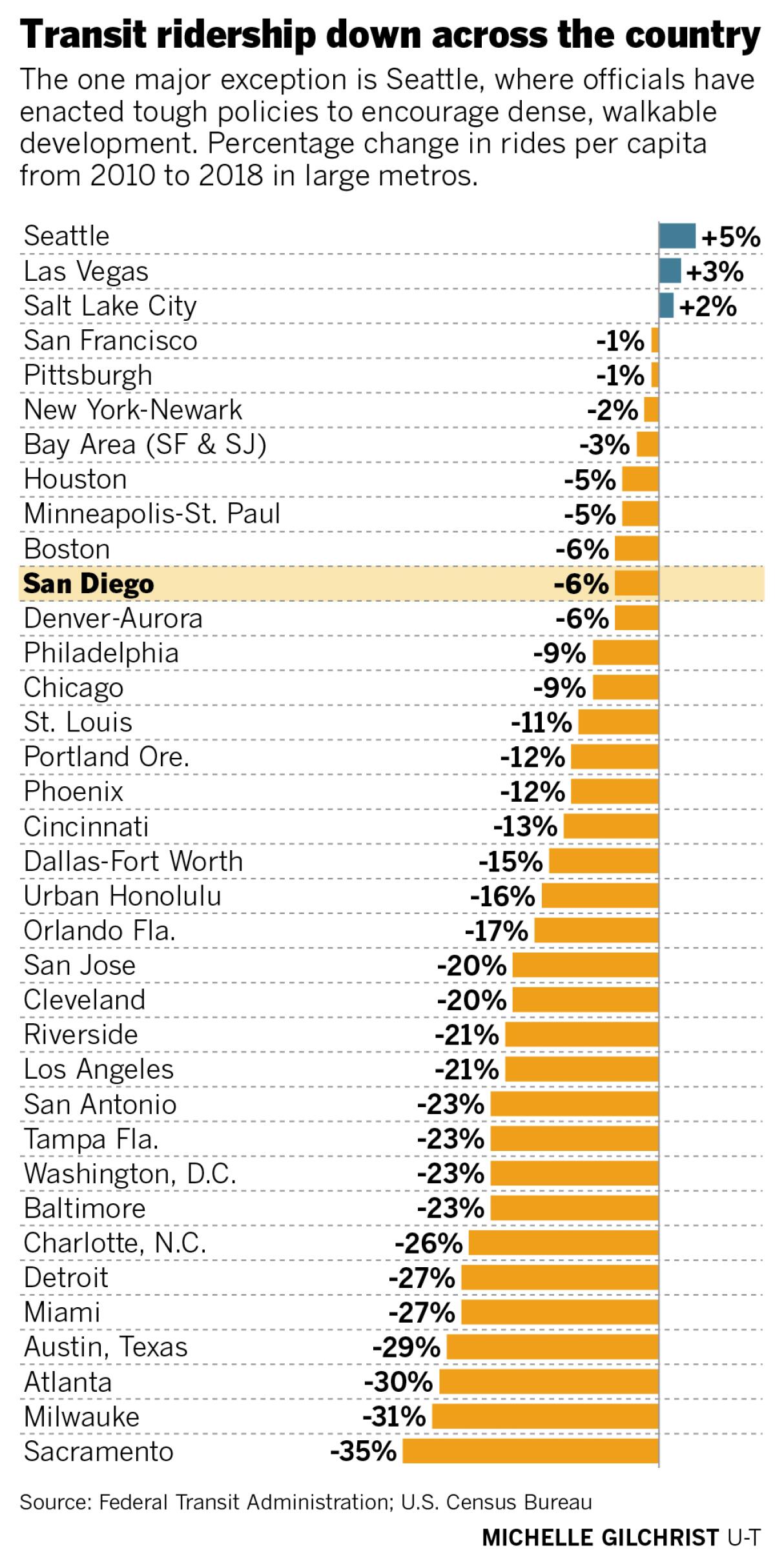

The ask comes at a time when many cities around the country — from Atlanta to Houston to Los Angeles — have invested heavily in public transit only to lose riders. Seattle is the only major metropolitan region in the U.S. that has seen ridership increase in recent years.

Those who hope to see San Diego follow Seattle’s example say it will take more than spending massive amounts of taxpayer dollars. It’s going to take something politicians in Southern California and beyond have been reluctant to do: Make it harder to drive.

“Los Angeles is very much a cautionary tale,” said Michael Manville, a professor of urban planning at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs. “You can’t take a region that is overwhelmingly designed to facilitate automobile travel and change the way people move around just by laying some rail tracks over it.”

Transportation experts have recommended bold steps for metropolitan regions attempting to get people out of cars and onto public transit, from eliminating parking in major job centers to encouraging dense neighborhoods with vibrant street life to ending freeway expansions and limiting suburban home construction. Most have also called for instituting some form of congestion pricing, such as highway and road tolls that fluctuate based on traffic.

“Los Angeles is very much a cautionary tale. You can’t take a region that is overwhelmingly designed to facilitate automobile travel and change the way people move around just by laying some rail tracks over it.”

— Michael Manville, a professor of urban planning at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs.

It’s unclear whether the San Diego region will see walkable urban communities sprout up around bustling new train stations, but the idea is gaining traction, at least in the region’s larger cities.

San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, arguably the most high-profile elected official in the region pushing for a major transit expansion, has called for a “balanced approach,” from building a new high-speed rail system to adding lanes to state routes 78 and 67.

It’s the kind of strategy for transportation planning that some say has led other cities to spend billions on transit systems that many people don’t ride.

In his own city, the Republican official has taken some major steps to increase density, including nixing parking requirements around transit stops and unveiling a plan to lift height limits on new construction in those same areas.

Still, transforming the region would likely take decades of dedication by local leaders and policies likely to upset many homeowners, said Mark Hallenbeck, director of the Washington State Transportation Center at the University of Washington.

“I won’t say it’s an insurmountable problem, but it’s really hard to change it,” Hallenbeck said.

“The heart of whether this will be successful or not is how much stuff are you going to build within walking distance of these stations,” he added. “Can you stop growth from going out to Santee and Poway?”

Road to the Emerald City

Hallenbeck said that a large part of Seattle’s success has been its urban growth boundary, which restricts how far out the city can build. The metropolitan area is also surrounded by water and ridge lines that deter sprawl.

At the same time, Seattle’s major employers, such as Amazon and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, along with associated biotech businesses, are all centrally located. The city’s major stadiums are also downtown.

As a result, traffic in Seattle is notoriously gridlocked, but its bus and light-rail systems are well used, according to an analysis of federal data out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Since 2002, the region has seen a per-capita ridership increase of 22 percent.

Over the same time period, the L.A. region saw a ridership decrease of 11 percent, while the Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth regions in Texas both saw a whopping 28 percent drop.

“I don’t think there’s a magic formula that people are keeping secret from cities,” said Yonah Freemark, a doctoral candidate in urban studies at MIT, who compiled the figures on his website The Transport Politic.

“You have to make sure it’s not so easy to drive around, and that means reducing the amount of parking that’s available or that is required for new (building) projects,” he added. “It means reducing the number of car lanes and, in some cases, increasing the taxes on gasoline.”

Many regions have blamed their transit woes on the economic rebound from the 2008 global financial crash, as well as the rise of ride-sharing companies such as Uber and Lyft. However, Freemark says that can’t be the whole story, as other cities impacted by those trends have made significant gains in transit ridership in recent years.

Beyond Seattle, cities throughout France, for example, have been seeing significant gains over the last decade, including a 9 percent per-capita ridership increase in Paris, a 19 percent bump in Strasbourg and a 43 percent jump in Bordeaux.

Freemark said that many of these cities could have chosen to sprawl into the French countryside but have instead actively restricted growth.

No place like home

San Diego faces some unique challenges when it comes to planning its multibillion-dollar 100-mph rail system. Most notably, the region’s employment centers are decentralized.

Downtown San Diego, the densest and easiest location to serve with transit, has only 5 percent of the region’s employees.

The largest job hubs are auto-centric Sorrento Valley and Kearny Mesa, but even those areas combined have only about 16 percent of the region’s workers.

San Diegans drive long distances all over the county to get to work, with major employment centers located from National City to El Cajon to Escondido and Carlsbad.

The San Diego Association of Governments’ ambitious rail plan includes laying hundreds of miles of track throughout the county to connect residential areas to these job centers. Agency experts are analyzing the region’s commuter patterns in an attempt to design rail service that lures commuters off the most congested highway corridors.

The lines, many of which are planned as subways, will go through existing residential areas with the added aim of encouraging dense development along the routes.

“I think this region is more suited to follow-up with transit-oriented development than any other region in the country,” said SANDAG Executive Director Hasan Ikhrata. “All California and the U.S. is designed around the car, around the interstate system. It took 50 years to have the land-use we have. It’s going to take 50 years to reverse it with the rail.”

To pay for it, top transportation officials are eyeing a one-cent sales tax increase on the November 2022 ballot that could bring in roughly $100 billion through 2062.

However, some outside experts have raised concerns about SANDAG’s proposed approach.

“It’s a pretty comprehensive commuter rail map, but it’s not going to address the sprawl issue,” said Ethan Elkind, director of the climate program at UC Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment. “If anything, it might make sprawl worse, and these tend to be expensive to run.”

Elkind said the region would do better to encourage employers to relocate to more central and walkable locations before building fixed rail lines.

“It’s about San Diego leaders working with their businesses to encourage them to locate back downtown along transit lines and give them some incentives to do so,” he said.

Funding a more limited transit system that services only the most urban communities could be more feasible now in San Diego. In the past, SANDAG would have needed to put its tax proposal before all voters in the county.

However, a new law spearheaded by Assemblyman Todd Gloria, D-San Diego, gives metropolitan planning organizations, such as SANDAG, the ability to place tax proposals before selected jurisdictions within a county.

For example, SANDAG’s board of 21 elected officials from around the region could decide to ask only the voters in the cities of San Diego, Chula Vista and National City to fund a new rail system. With two-thirds voter approval, the new levy would only be enacted in those cities.

That would eliminate the need for support from North and East County communities that have routinely opposed transit expansions.

Such a sub-regional ballot measure could concentrate new rail lines within the most urban communities, eliminating the need to run long and costly service to far-flung parts of the county.

Emerson Smith writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.