Frank Lloyd Wright’s Millard House (La Miniatura)

- Share via

| Advertisement |

Frank Lloyd Wright's La Miniatura

Although Frank Lloyd Wright used to call it "this little house" as a term of endearment and gave it the Spanish name La Miniatura, the 1923 concrete block home he designed near the Rose Bowl in Pasadena's Prospect Park historic district today seems anything but miniature. Its hefty and alluring Maya facade rises like a temple from a tree-canopied hillside, just visible through an iron gate on sloping Rosemont Avenue.

The Alice Millard house, as it's more frequently called, is the first of Wright's famous "textile-block" homes -- the term designating his innovative concept for stacking decorative concrete blocks, held together like so much sturdy fabric with mortar and steel threads of rebar.

The Millard house was the first of Wright's four textile block homes and the only one without that rebar -- an unforeseen blessing, as that the rebar in the subsequent houses, all built prior to the invention of epoxy coatings, rusted and degraded the concrete. As a result, the Millard house has fared better through the years of weathering and earthquakes.

Because of its location, partially hidden by Wright's own landscaping, the Millard house is less known among the general public than the other textile block homes -- Ennis, Freeman and Storer, all built between 1923 and '25. But many historians regard the Millard house as the finest, and so does Eric Lloyd Wright, the architect's grandson. The longtime Southern California architect had a simple answer for why critics revere his grandfather's Pasadena landmark so much:

"The way he set the house in that glen," Eric Lloyd Wright said.

Frank Lloyd Wright had designed a prairie-style house for antiques dealer Alice Millard and her husband in Chicago, and here in Pasadena he persuaded Millard to trade a flat lot that she had purchased nearby for far more uneven terrain that inspired his vision of a sunken garden.

"My eye had fallen on a ravine nearby in which stood two beautiful eucalyptus trees," Wright later wrote. "The house would rise tall out of the ravine gardens."

The two eucalyptus trees are still there, forming a cathedral more than 100 feet high over a lily pond in the gully. As he envisioned it, "Balconies and retraces would lead down to the ravine from the front of the house." The way the house is matched to its setting is often compared to Wright's more famous Fallingwater, the Pennsylvania house poised over a waterfall.

True to his word and his eye, in building the Millard house Wright created a landmark residence that belied his preference for the horizontal. It made a singular vertical impression, evoking a Maya monument rising from the jungle when viewed from the downhill side. The design exemplified Wright's quest to find an indigenous American architecture following a six-year sojourn in Japan, and it signaled his continuing interest in the pre-Columbian culture of the Maya, an interest that dated to his work in Chicago a decade earlier.

Vertical spaces created between exterior columns outline casement windows and doors, contributing to the building's general upward thrust. The low ceilings so familiar to fans of Wright are here too, a challenge to anyone taller than 6 feet.

Millard wanted an "old world" European elegance but allowed her architect to indulge his affinity for Maya-inspired decorative frieze and architectural massing -- as long as she could add her own touches, visible today in the ornate fireplace screen in the living room, the carved Italian doors and the crouching stone lions guarding a covered walkway.

Circulation in the house revolves around a central chimney, with the main entry at the middle level of three, and all three bedrooms in the main house stacked to face Prospect Crescent. Some would say the mezzanine, which provides passage to the master bedroom while overlooking the two-story-tall living room, offered a glimpse of the plan for the Guggenheim Museum 36 years later. The unorthodox layout is as intriguing as it is disorienting, causing some first-time visitors to lose track of where they are and how rooms relate to one another.

Lloyd Wright, the construction supervisor on the main house, created a detached studio at Millard's request two years later. It provided a place to display her antiques as well as another bedroom, kitchen and dining room -- bringing the property's living space to 4,200 square feet.

A covered walkway seamlessly joins the studio to the main house using concrete block piers matching those in the original construction.

Those blocks represent what Wright sought to achieve, something that he found missing from other homes in the area: "a distinctly genuine expression of California in terms of modern industry and American life."

To this goal he added another: to create an organic whole using the natural materials of concrete and wood.

In adopting this new mode of design, Wright saw himself as "the weaver," knitting the concrete blocks together with the method of standardization made possible by the machine -- a form of progress rejected by the Arts and Crafts movement, whose American temple, the Greene & Greene Gamble House, is just a quarter-mile away.

Ironically, the blocks themselves, made locally from wooden molds that expanded and contracted, did not turn out to be uniform. Wright sparred with the home's contractor and complained that the team had no skilled labor. The builder's relatives, he said, set the blocks.

The 16-inch concrete squares are scored in a cruciform pattern suggestive of primitive American Indian design. They were stacked in a double wall, 12 inches thick, with space in the middle for insulation.

Embarking on this experiment immediately after returning from Japan appears to have led Wright toward a fusion of Asian with Meso-American, creating a house where East meets West.

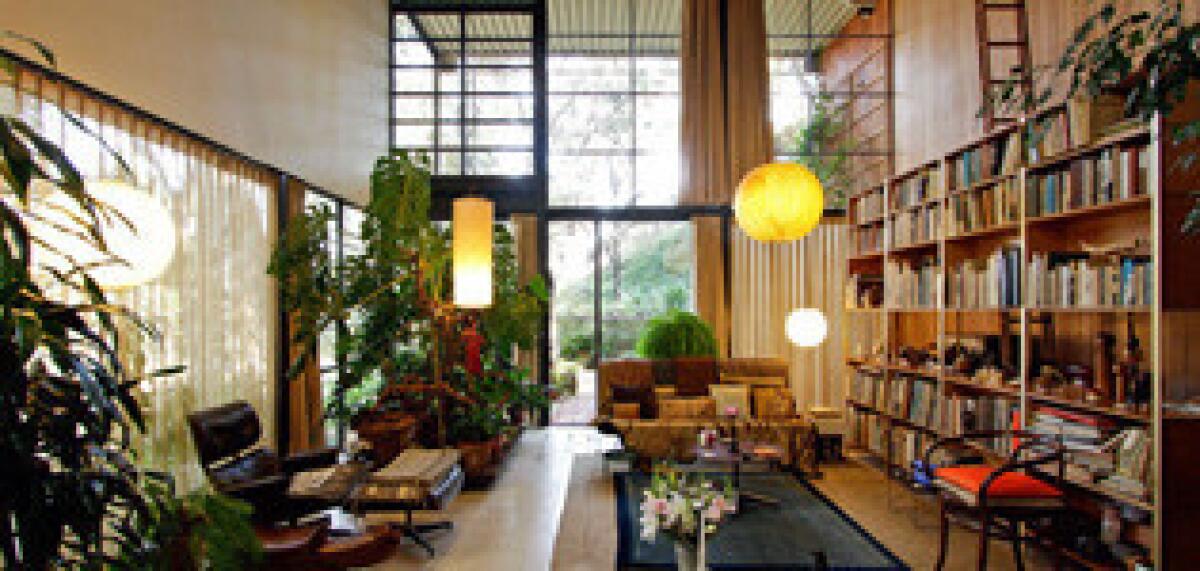

That blending of traditions can be seen in the way the heavy slab suspended over the fireplace is encompassed by the airy, two-story-high living room, the way the weight of the masonry is juxtaposed with the fine redwood ceilings and windows. Maybe most remarkable is the way Wright arranged for perforations in the blocks to mitigate the masonry mass in general, creating the feeling of a concrete shell lighter than it actually is.

The light-washed living room, with its long row of artfully framed glass doors facing west over the expansive water garden, offers an unforgettable vision of nature unbound and subdued at the same time -- emerald tranquility achieved in the shadow of a city dominated by a blazing sun.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![[DeAratanha, Ricardo -- B582312471Z.1 SANTA MONICA, CA - AUGUST 21, 2012 - Craig Ehrlich and 7-year-old daughter Leah walking on the wooden deck in front of his accessory house in Brentwood, August 21, 2012. The original house was awarded an AIA/LA Decade award as one of the best buildings of the last ten years. Ehrlich bought the lot next door and had architects John Friedman and Alice Kimm design this new building, with a pool in between, making a compound with a great outdoor area. This new house is one of the very first that will be certified LEED for Homes in Southern California. (Ricardo DeAratanha/Los Angeles Times).] *** []](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/d1253bd/2147483647/strip/true/crop/315x150+0+0/resize/1200x571!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F09%2Fd7%2F48fd487ae3ec04cdbf3fc879017c%2Fla-lh-lahmadvehrlich-photos)