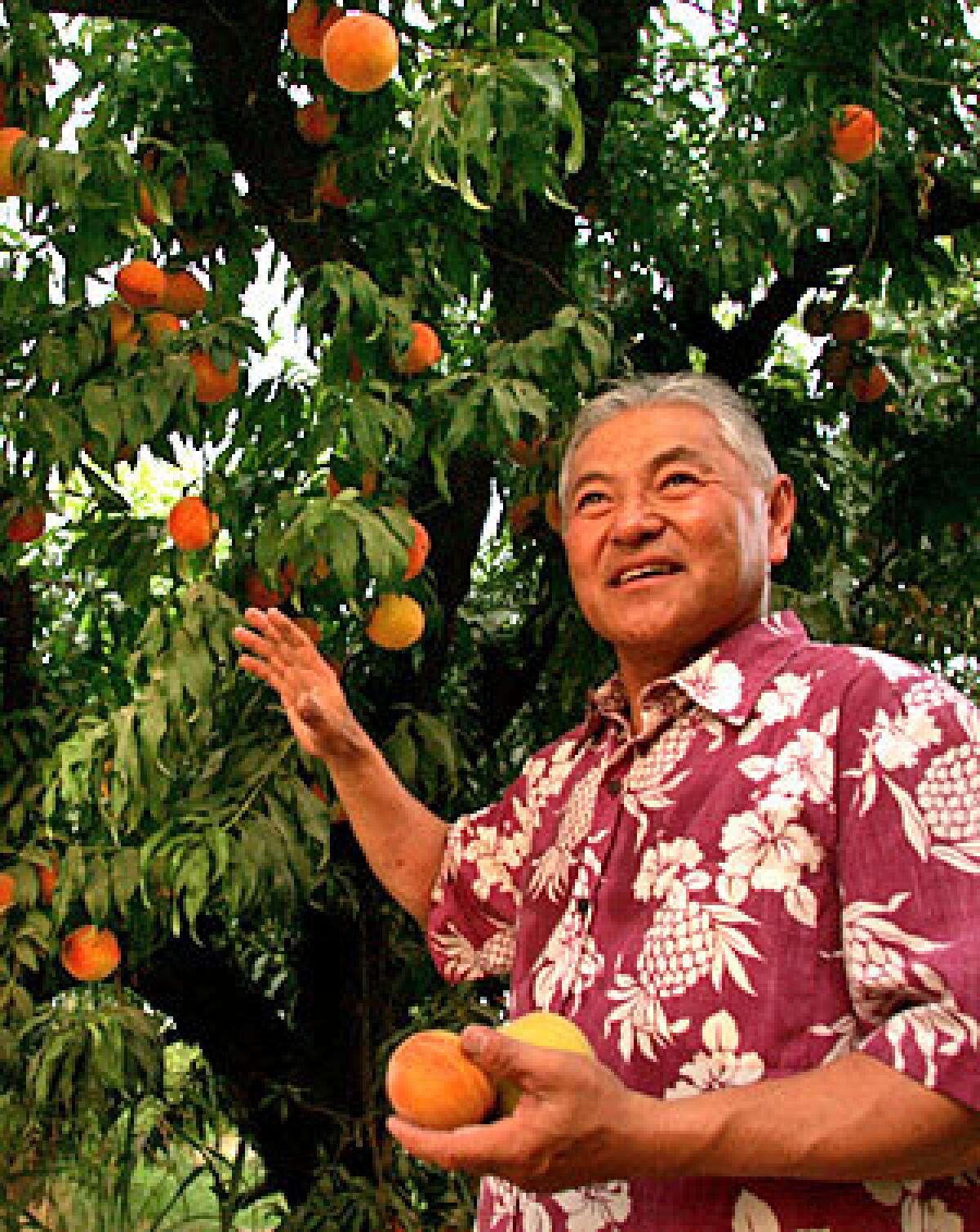

Peach farming: risk, worry and obsession

- Share via

Summer approaches with the promise of fat, juicy peaches, sweet grapes and a farmer’s angst.

On my 80-acre organic peach, nectarine and raisin farm in the San Joaquin Valley, as the days grow longer, the opportunities grow greater to worry about the weather, markets and growing conditions. I begin to doubt myself, which compels me to go out and check the fields one more time in the evening, to make sure the irrigation water reaches the ends of rows and thoroughly soaks roots or to reexamine the fruits to make sure they remain safe on the tree and haven’t aborted with an abnormal April heat wave. My anxiousness makes me a better farmer, but I don’t sleep well at night.

As the weather changes, my anxiety increases. My blood pressure rises with the temperature. Each dark cloud on the horizon has my name written on it. We need rain but not too much; the orchards will love a cleansing shower, but that, in turn, will cause mildew to grow in the grapevines. I can’t help but think of the worst and anticipate things will go wrong. It’s part of my daily work ritual.

I grow apprehensive and over-analyze everything, plagued by a combination of denial and astute observation. For example, I conclude that I must have Zen worms on my farm -- they force me to ponder and reflect: If I discover only one worm but can’t find more, did I find the only worm? Or is that just the only worm I discovered? Questions only lead to more questions.

Harvest approaches with excitement and exhilaration. I’m absorbed by the challenge, invigorated by the hard physical work, which could prove to be the reason that things may turn out wonderful. Just before summer harvest, farmers constantly play a poker game of “all in” and bank on their labor for success. It’s the only hand we can play.

I act compulsively, knowing there’s always more work to do, weeds to shovel, pests to battle and old equipment to repair. I’m called to action, believing any act is better than nothing. The longer days allow more hours to work outside, and so I burden my family with late dinners (trying to convince them that late meals are very European).

Night saves me from exhaustion. I have to stop sometime, although I’ve become an expert at driving the tractor in the dark, using sounds and echoes to guide me down a vine row (on my old equipment, lights often don’t work).

Watch and wait

I am vulnerable to outsiders who may make a very innocent comment: “It’s been a cool spring.” For the next few days I fret and wonder: “Has it been that cool? What’s normal? How did I miss that change in weather?” The Internet makes for a terrible companion because now I can study the weather even at night with radar and satellite imagery.

I farm with fear. No one will want my fruit. With the recession, market prices will collapse. Freak weather and global warming will destroy a crop. Farmers are experts at disasters. For 30 years I’ve seen a lot of weather conditions, yet nature can fool you with something new each season -- like the 100-degree temperatures we had in April.

I try to postpone my distress by ignoring it. I mask my nervousness behind a stoic farmer’s face. I nod a lot, pretending all is well. I internalize fears with soft sighs, confining the anxiety to where it can do the most damage without burdening others. Farming requires sacrifices, most often of ourselves.

I make mistakes and scold myself. I learn through trial and error, which is then amplified in the summer. Problems earlier in the year will be multiplied closer to harvest. In the 10 rows I disked too soon after a winter rain, the earth is now compressed, and irrigation water is slow to drain, creating microclimates for pathogens and plant diseases. I can’t escape my past.

Hopes and dreams

I carry a frustration: a goal to produce the perfect peach but knowing that’s impossible. Ideal growing conditions exist only in my dreams. Yet good farmers dream of growing the best: After all, we eat our own produce and become our own harshest judges.

Just before summer, the real and the imaginary collide. Imagination helps me envision something great happening in my fields. The best pruners are those who in the winter can imagine the summer sun filling a tree leaf canopy. But did I do that? My skills are tested each year. The approaching harvest makes for a brutally honest evaluation.

The risk of shame is part of this season, a fear of failure balanced with the hope of creating something special. In the end, I farm and grow a lot of humility and confusion. I want to be an artisan, employing both the science and technology of farming with the art of reading weather patterns and sensing nature at work on my land.

Then images of the starving artist enter my thinking: to grow beautiful peaches or nectarines and die poor -- but having created art!

Ultimately, I begin to take myself much too seriously. This is just a peach. I’m just a farmer. Obsessive behavior is part of caring, all part of a richness at harvest, all natural and wonderfully human. I can taste emotions in the summer. You can’t have wonderful flavor without risk and worry. Without the bitter and sour you can’t taste the sweet and savory.

Masumoto is an organic farmer outside of Fresno and author of “Epitaph for a Peach.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.