The face as frontier

- Share via

Society may not be quite ready for the day when a dead person’s face is recycled for the living — but that day is coming nonetheless.

Such an operation would give new life to someone severely disfigured by burns, cancer or an accident, allowing the person to exist free of the stares and shock their appearances often evoke. The procedure would be more straightforward than the many reconstructive surgeries such victims usually must endure.

Already, doctors at the University of Louisville in Kentucky say they hope to soon select a candidate for the operation, possibly within the year. The same team performed the first U.S. hand transplant (and second in the world) in 1999. Surgeons in other countries are pursuing the possibility of a face transplant as well. All agree it’s just a matter of time until the world’s first face transplant.

The technical skills needed for the surgery are well-established. Organs are routinely transplanted from one person to another, and even some limb transplants have been successful. Those operations, once remarkable, have become almost commonplace.

But an internal organ, or even a hand, is dramatically different from the wholesale appearance change that surgeons are now considering, the Louisville surgeons acknowledge.

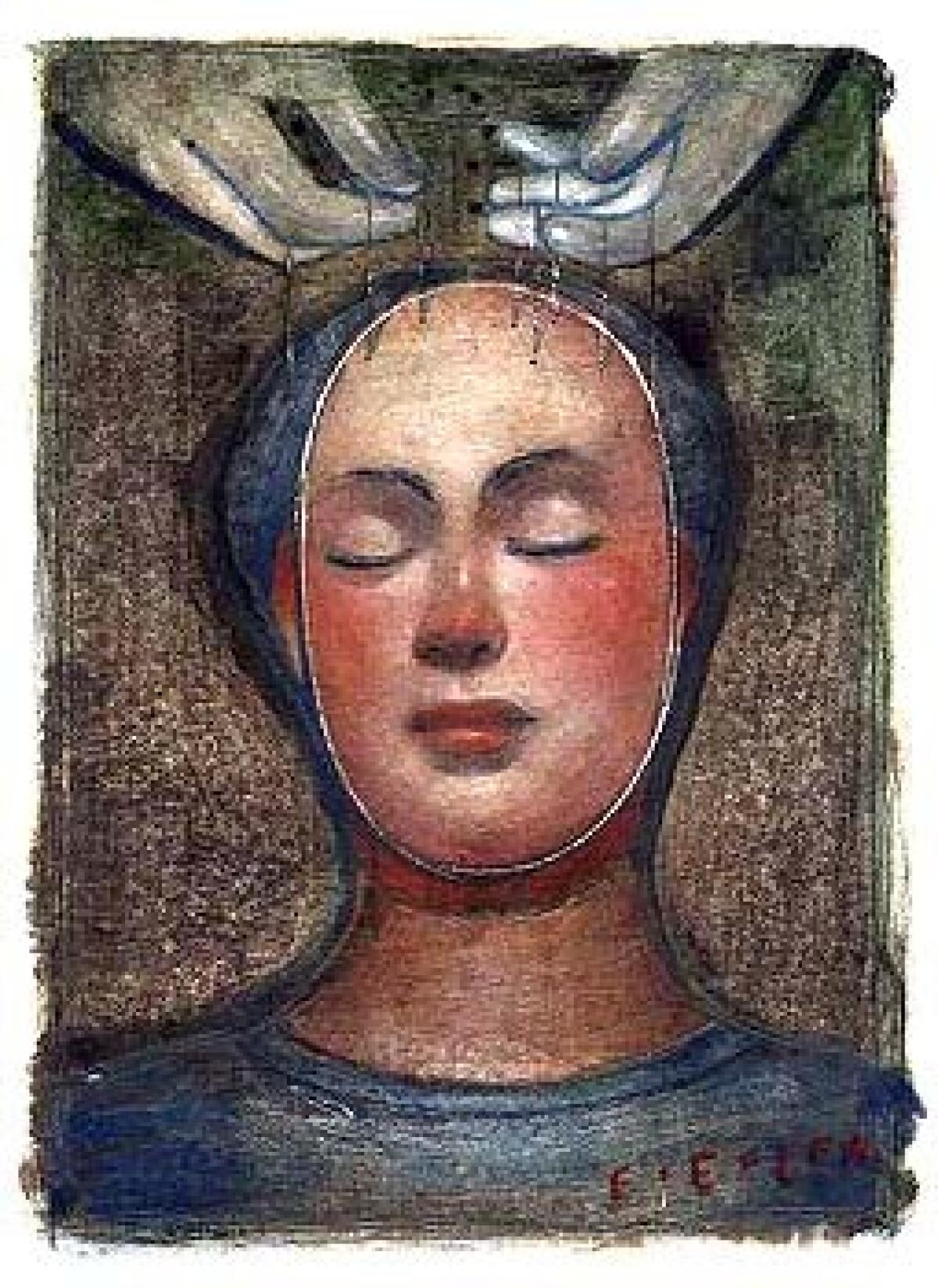

Faces are the most visible portion of human identities. They’re how we think of ourselves, how others recognize us. The possibility of altering that identity so radically — a science fiction plot device made real — could make people recoil, perhaps eroding support needed for the operation.

In Britain, reservations from the medical community have indefinitely stalled plans there for a facial transplant. Aware of the sensitive nature of such surgery, the doctors in Kentucky are treading carefully. The team is exploring ethical arguments for and against the procedure, using studies and surveys to gauge likely public reaction.

If the results are favorable, the surgeons are prepared to proceed. Even if the reaction is an unexpected negative, the surgeons say the notion eventually will become accepted.

“As for surgical technique, a face transplant could have been done 10 years ago,” said Dr. John Barker, director of research for the surgeons’ group. “And now with the preliminary results we have in our ethics studies, we think it’s time.”

The group is evaluating potential transplant recipients, as is a group of collaborating physicians in the Netherlands, he said. French surgeons also are said to be considering the operation.

Public acceptance is not the only roadblock, however. Many doctors remain unconvinced of the medical need for the operation, questioning whether the risks of the surgery outweigh its potential value. A face recipient would need to take powerful medications for the remainder of his or her life to prevent rejection by the body. He or she also would face the possibility that the transplant would fail — and the unknown psychological effect of having one’s cardinal form of identity, even if disfigured, so wholly transformed.

“Faces,” said a British advisory panel in a published report, “help us understand who we are and where we come from.”

*

A unique appearance

A face transplant would rely on microsurgery — the connection of very small nerves and blood vessels. In the first such surgeries, doctors probably would remove a layer of donor skin containing muscle, nerves, tendons and blood vessels. The recipient’s disfigured face would be removed down to the bone and cartilage, and the donor face draped across it, fitted and reattached.The result would be a hybrid face, with features from both donor and recipient, Barker said. The team has tried to anticipate the cosmetic result by experimenting on cadavers. The result is a face that resembles both donor and recipient, perhaps similar to a relative of one or the other.

“It’s surprising how different the recipients look” from the donors, he said. “If you transplanted the entire bone structure, however, they would look exactly like the donor.” (That, however, is not currently possible.)

The groundwork for face transplantation was laid about five years ago when French surgeons transplanted a hand. Since then, more than 20 hand transplant surgeries have been completed worldwide, Barker said.

Surgeons also have become adept at reattaching hands, scalps and large parts of faces that have been torn off in accidents. In many of those cases, the tissues being reconnected are mangled and unclean, requiring herculean surgical efforts in an emergency setting. Reconstructive surgeons also routinely remove tissue from other parts of the body and reshape and attach the grafts to the faces of trauma patients.

“Technically, what our reconstructive surgeons do to reconstruct a face is probably harder than doing a face transplant,” Barker said. “A donor is in pristine condition. Everything is planned. You remove all the tissue you need from the donor — even more than you need. You cut away the excess you don’t need.”

Like people who receive new hearts or other organs, face transplant recipients would have to take medications for the remainder of their lives to prevent the body from recognizing the donor tissue as foreign and rejecting it.

*

Weighing the risks

The long-term risks of these drugs — and the unforeseeable psychological effect of wearing someone else’s face — were cited by the Royal College of Surgeons of England as a reason to delay such surgeries.A reconstructive surgeon, Dr. Peter Butler, of London’s Royal Free Hospital, had prompted a national debate in England when he said he wanted to perform the surgery.

The idea is “worthy of study,” the Royal College of Surgeons concluded in its resulting November report, but “until there is further research and the prospect of better control of these complications, it would be unwise to proceed with human facial transplantation.”

In the United States, no such official decree is in the works. The Louisville surgeons need only receive consent from their hospital’s institutional review board to proceed with the surgery. (Institutional review boards are set up to oversee medical research at a particular medical center or research facility.)

However, American reconstructive surgeons echo some of the same concerns as the British.

“While we can sometimes do wonderful things technically, can we follow up with the other things? The tissue matching. The rejection phenomenon. The social issues. Can we overcome all the other issues?” said Dr. James Wells, a Long Beach plastic surgeon and immediate past president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. “They haven’t answered all the questions,” he said of the Louisville team.

Although donor and recipient would share several tissue-typing characteristics, anti-rejection drugs would still be needed to suppress the recipient’s immune system so it wouldn’t attack the donor tissue. The drugs carry long-term risks, such as hypertension, diabetes, kidney toxicity and infection.

“It may be time to consider face transplantation in people with absolutely devastating injuries. This would probably give you the best function and cosmetic result,” said Dr. Rod Rohrich, president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons and a plastic surgeon at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

“The problem still is with the drugs. If we could solve that, we’d have face transplants all the time,” he said. “But, long-term, these drugs themselves can cause problems. The risk may not be worth the benefit.”

It’s also possible that the drugs could fail and a recipient’s body would reject its new face. Barker said a second transplant would be attempted in such cases.

A candidate for a face transplant would need to understand the ramifications of a failure, said Eric Trump, an ethicist at the Hastings Center, a bioethics research institute in Garrison, N.Y. “A face going into rejection, I think, would be fairly terrifying. There would be bloating, discoloration. Then what would you do?”

*

Meeting a need

Face transplant candidates may be more accepting of the risks than some doctors. In a recent study conducted by Barker, 300 people were asked how much risk they would be willing to accept to receive a new body part, such as a kidney, hand, partial face or complete face. The respondents included people with no experience in disfigurement, people with disfigurements and people who had received organ transplants. Most people said they would take more chances to replace a completely disfigured face.“This must be the most terrible thing to live with,” Barker said. “In society, we don’t see these people because they don’t go out.”

Although some people with devastating facial injuries adjust and thrive, others’ lives are ruined, said Amy Acton, executive director of the Phoenix Society, the nation’s largest burn survivor organization.

“I think there are many people who live with a facial difference successfully,” said Acton, a burn survivor whose injuries were to the neck, torso and limbs. “But there are still people who never get to this place, and maybe this option would make a difference for them. In our culture there is a tremendous amount of pressure to look ‘normal.’ As a group, we would not want to deny the possibilities that are out there.”

While other types of transplants are conducted to save lives, treat disease or improve body function, face transplants for aesthetic reasons are no less important to the person who seeks one, said ethicist Trump, who received a kidney transplant five years ago.

“Our bodies are important to identifying who we are,” he said. “If you are living with a face that has been burned off or ravaged by cancer, I think it’s important to have this option.”

A face transplant, even with its risks, might be more appealing than the alternatives, said burn survivor Barbara Kammerer Quayle. After surviving a rear-end car crash in 1977, Quayle underwent approximately 20 operations over four years to reconstruct her face.

Reconstruction strategies include skin and muscle grafts and prosthetic implants; someone with a severe injury could need a dozen or more surgeries over the course of many years.

“While there are many possibilities for people with reconstructive surgery, sometimes people have to come to the conclusion that there is just so much that can be done,” said Quayle, who works at UCI Medical Center in Orange, counseling other burn patients on recovery and image enhancement. “If it’s a serious burn, and face transplantation is an option, I say hallelujah.”

Dennis Gardin, 47, could have been a candidate for facial transplant. He was 14 when he was burned over 70% of his body in a motorcycle accident. He had more than 50 operations while spending eight months in a hospital. When he was released, he wouldn’t leave his house for two years. “I was so ashamed with my appearance and so afraid that no one would accept me the way I looked,” he said.

Gardin, now a motivational speaker who lives in Detroit, began having reconstructive surgery but, after four years, reached a breaking point.

“I never forgot that day,” he said. “I was to be admitted for another surgery and when I got my overnight bag to pack I realized I hadn’t unpacked my bag from the last operation. I broke down and cried. That was all I was doing, having surgery. I asked my mom, ‘Please don’t make me go back again.’ I was so tired of the hospital, surgery and pain.”

He chose to live with his appearance and, many years later, said he was comfortable with it. Gardin said he wouldn’t want a face transplant now, but added: “I think we are fortunate to be in a time where there are these options.”

*

Not a quick fix

A face transplant would not be an easy fix, even for severely burned patients. They would still have some scarring and would require extensive psychological adjustment.The first candidate for a face transplant would be someone who has been disfigured for some time and has the emotional wherewithal to deal with the transplant, Barker said. There is no way to predict how the recipient might feel with a new face, he added.

Psychological hurdles exist on the other end of the transplant as well, experts noted. Who would donate their loved one’s face?

“Would parents, for example, be willing to have their brain-dead child’s face excised?” said Trump. “Would anyone want a loved one’s face removed after death? I think this is a major obstacle to the procedure becoming routine.”

Donor organs and tissues already are in short supply, said Wells, the Long Beach plastic surgeon. Finding appropriate face donors and recipients will be even more difficult.

“Your donor pool is going to get extremely narrow if you consider race and ethnicities,” said Wells. “If the donor pool is as narrow as I’ve suggested, I don’t see [face transplantation] happening any time quickly. I think it will be very difficult.”