Healthcare history: How the patchwork coverage came to be

- Share via

Workers swarmed through Henry J. Kaiser’s Richmond, Calif., shipyard in World War II, building 747 ships for the Navy. The war “had siphoned off the most hardy specimens,” a newspaper reported, so Kaiser was left with many workers too young, old or infirm to be drafted.

The workers needed to be in good health to be effective on the job, and Kaiser offered them care from doctors in company clinics and at company hospitals. The workers paid 50 cents a week for the benefit.

It was something new in industrial America — a bonus offered to attract scarce labor while wages were frozen during the war.

The war ended, the workers quit the shipyards, leaving behind hospitals and doctors but no patients. So the company decided to open the system to the public — and that’s how generations of Californians who never heard of Kaiser shipyards have since gotten medical care.

It is just one example of the way America’s health insurance system has grown into the strange patchwork program it is today.

Most of us get health insurance through our jobs, a system puzzling to the rest of the industrial world, where the government levies taxes and offers health coverage to all as a basic right of modern society. But for many Americans, their way feels alien — the heavy hand of government reaching into our business as some bureaucrat tells doctors and patients what to do.

We always seem to fight over the role of government in our healthcare. In 1918, California voters defeated a proposed constitutional amendment that would have organized a state-run healthcare program. Doctors fought it with a publication declaring that “compulsory social health insurance” was “a dangerous device invented in Germany, announced by the German Emperor from the throne in the same year he started plotting and preparing to conquer the world.”

The amendment was defeated by a huge margin.

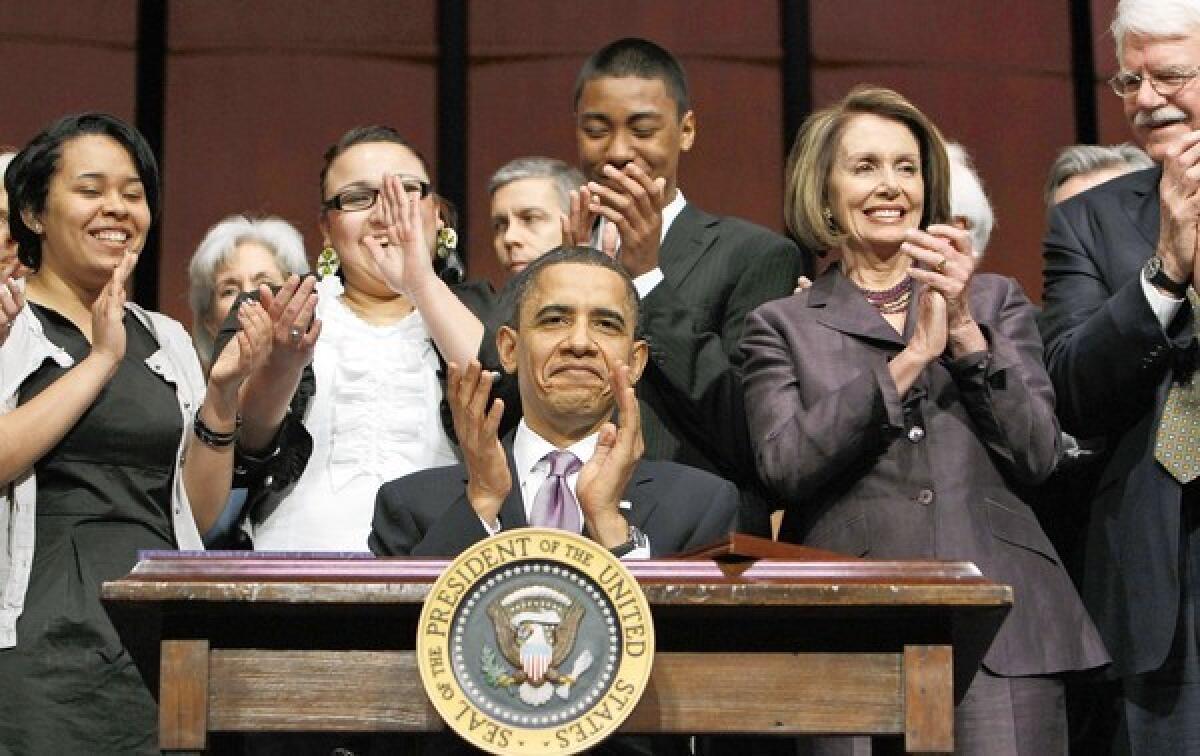

This year’s presidential and congressional election campaigns will feature intense argument over the Affordable Care Act signed by President Obama in 2010, the most ambitious effort yet to bring health insurance to all Americans. Everyone is required to have health insurance, and all but the poorest citizens face a tax penalty if they don’t comply.

For liberals, the act is a culmination of the dream to complete the work of PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. For conservatives, many of whom scornfully refer to the law as Obamacare, it is big government run amok. The first battleground will be in theU.S. Supreme Courtnext month, when the justices hear arguments on whether it is constitutional for the federal government to make citizens buy health insurance.

The long-standing tension between public and private healthcare in America has produced a unique and confusing way to provide protection against the cost of ill health.

It was Teddy Roosevelt’s Bull Moose party that first suggested, in the 1912 presidential campaign, that Americans would need help paying their medical bills.

Medicine was becoming safe and even effective. Doctors could treat typhoid and diphtheria. Hospitals were becoming places that could help you get better rather than serving as dumping grounds for the insane or warehouses for paupers.

Being able to treat sickness meant that healthcare started to cost more.

When FDR became president in 1933, the committees that developed the concept of Social Security for him also considered national health insurance. Roosevelt flirted with the idea but never threw political muscle behind it.

After Harry S. Truman became president in 1945, he called on Congress to provide national health insurance but could never bring it to a vote. Opponents included theAmerican Medical Assn., which in 1948 asked each of its members to kick in $25 to fund a campaign warning that Truman’s “socialized medicine” plan could lead to socialism throughout American life.

Health insurance, when it did emerge on a mass basis, came from the business world, as exemplified by the Kaiser shipyard story. World War II-era employers faced government-mandated wage freezes to prevent them from competing with dollars for scarce workers, which would drive up prices and cause inflation. But the IRS allowed companies to offer benefits up to 5% of the value of wages without counting them as taxable income.

The ruling became permanent in 1954, creating the foundation for the insurance system we have today.

After the war ended, the powerful labor union movement focused on expanding health coverage as well as boosting wages. Health insurance became a standard feature in labor contracts. Elsewhere in the economy, nonunion employers too decided it was a good tool to attract workers.

And then, in 1965, after years of hearings and campaigns, the federal government dived into healthcare in a big way.

For years, there had been talk of the needs of the elderly, who couldn’t afford the hospital bills that came with the ravages of old age. Old people were a sympathetic and deserving group for politicians. President Lyndon B. Johnson, armed with the power and prestige of a landslide victory in 1964 and the support of big Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, pushed through a legislative three-layer cake.

For people ages 65 and older, there would be Medicare Part A. It would pay their hospital bills with taxes collected from workers, just as the government collects taxes from workers to pay for Social Security retirement checks.

The second layer on the cake was Medicare Part B, set up in a fashion to win over doctors: They would receive their usual and customary fees for each thing they did for patients.

The third layer on the cake was Medicaid, a federal-state program of care for the poor.

Even after Medicare became law, there were great fears it might be too controversial to work. Would doctors refuse to see Medicare patients? Would Southern hospitals agree to dismantle their segregated wards and have patients of different races sharing the same rooms?

The doctors didn’t strike. And the hospitals were immediately integrated without protest.

Today, Medicare seems like the birthright of every American who reaches age 65. John Breaux, a former U.S. senator from Louisiana, likes to tell the story of an elderly woman who accosted him at an airport, declaring, “Don’t let the government mess with my Medicare.”

Seniors had their national health insurance, and the Democrats thought they had a winning issue. Bill Clinton entered his presidency in 1993 with an ambitious plan to extend national health insurance to everyone.

Hundreds of experts spent hours behind closed doors drawing up intricate plans. But Congress felt excluded and insulted, and the plan never came to a floor vote in the House or Senate. Its fate was sealed when the GOP made big gains in 1994, giving Clinton a Republican House to deal with for the rest of his presidency.

The big plan had failed.

When President Obama approached the health insurance dilemma, he avoided the Clinton tactic of creating a detailed blueprint without input from Congress.

Instead, he relied on the congressional process. It was filled with deals.

Key to the plan was a mandate that everyone buy into the system; it was the best way to spread out the costs of illness. The insurance industry gave up the power to reject people who might be sick in return for getting a guarantee of 34 million new customers.

Drug companies agreed to cut their charges under Medicare Part D, Medicare’s prescription drug plan created in 2003, as long as the government wouldn’t force them to negotiate on prices.

The process would be run through the existing framework of private insurance companies. This infuriated liberals in the Democratic Party, who wanted a “public option,” a new plan that would be like Medicare.

Even if the Supreme Court throws out the mandate and the Republicans sweep the presidential and congressional elections, it seems a safe bet that some provisions in the Affordable Care Act will stay on the law books.

People already enjoy some benefits and won’t want to give them up: There are no longer any lifetime limits on insurance benefits, people on Medicare are getting more help in covering the cost of their prescriptions and you can keep your children on your health insurance until they reach age 26.

This places a few more patches on the national healthcare quilt.

That’s the American way.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.